Paris Progress So Far

Air Date: Week of December 4, 2015

The opening plenary of COP21 (Photo: UNclimatechange, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

PARIS CLIMATE TALKS – PROGRESS SO FAR: The COP21 in Paris could well be the most important climate conference so far, as negotiators from around the world try to hammer out a deal to forestall climate chaos. Host Steve Curwood and veteran observer Alden Meyer from the Union of Concerned Scientists discuss how the talks are going one week in, and what challenges and sticking points remain as we head into week two.

Transcript

CURWOOD: COP21 organizers say some 40,000 people are expected to participate in one way or another over the two weeks of these talks, and more than 180 countries have reported self-determined action commitments for reducing global warming emissions. These are called Intended Nationally Determined Contributions, or INDCs, and they are in sharp contrast to commitments under Kyoto, which mandated a narrow range of reductions for just the developed nations. Joining us now, as talks head into their final week, is Alden Meyer of the Union of Concerned Scientist, a veteran of 20 of the 21 COPs – dating back to 1994.

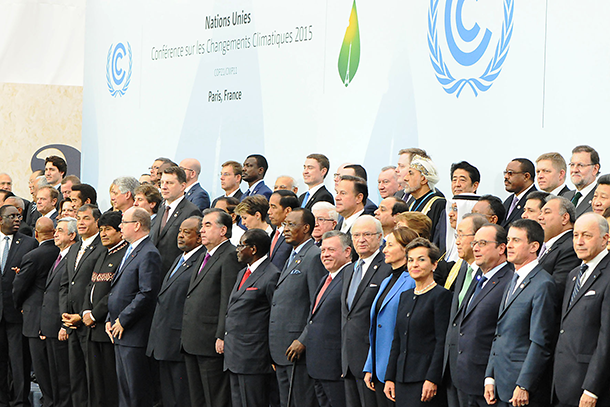

MEYER: This one is by far the biggest, and I think there's more momentum going into this COP for an agreement than there has been for any of the previous ones. There's certainly more engagement by heads of state, both from developed and developing countries. They were just here on Monday, over 150 leaders from around the world, and it's clear that they all want to see an agreement at the end of next week here in Paris. It remains to be seen how ambitious and comprehensive that agreement is going to be.

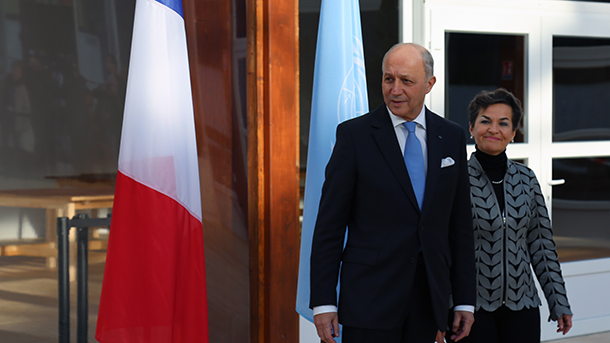

Laurent Fabius, the President of COP21, and Christiana Figueres, Secretary of the UNFCCC (Photo: UNclimatechange, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: What's motivating more cooperation this time, do you think?

MEYER: Well, I think the impacts of climate change are ever more evident to people around the world, countries are aware of the serious nature of what's coming at us if we don't take greater action. I think also the change in the economics of the solutions is having an impact. The fact that renewable energy prices has come down so dramatically in the last few years is making people realize that they can take ambitious action and have it actually help their economies, not hinder their economic development.

CURWOOD: What's the quality of the agreement you expect to come out of here?

MEYER: Well, we hope to get an agreement that recognizes that we have a gap between the commitments that have been put forward by countries so far, and what we need to do if we're going to have a chance to stay under the two degrees Celsius limit, 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit limit, that President Obama and other leaders agreed to in Copenhagen six years ago. And we need a process that gets countries to return to the table relatively quickly to ramp up the level of ambition of their commitments, certainly no later than the end of this decade. We can't afford to lock into place the current level of ambition out to 2030 and think that we have a chance to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

More than 150 world leaders present at the beginning of the Paris climate talks gathered for a photo op. (Photo: UNclimatechange, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: You mention the two degree target, but speaking from your perspective, from the Union of Concerned Scientists, how safe is that as a limit?

MEYER: We would not use the word "safe". I mean, you can see what is happening around the world now in terms of climate-related impacts at less than one degree Celsius, so the reality is there really is no safe level. I think what you have to look at is sort of two degrees as a defense line, but if we go beyond that we increasingly get into very dangerous territory. And, frankly, scientists are concerned about where are the tipping points, where are the irreversible impacts where you can't turn things around, and the reality is we don't know exactly where those are. So we have to be very cautious about how great an experiment we run with the planet in terms of temperature increase.

CURWOOD: We've been talking about limits for emissions of greenhouse gases. What about the need to have an international agreement that deals with the question of adaptation, updating the agreement?

MEYER: Well, that's the other side of this. There needs to be a recognition, even if we succeed in holding temperature increases under the two degree Celsius goal, that the world is going to experience increasing impacts of climate change in coming decades, just on the basis of the emissions we put into the atmosphere over the last century and a half. We're committed to almost 1.5 degrees warming no matter what we do, if we turned emissions off overnight, which of course we are not going to do, and we're only a little under one degree of warming experience to date. So you can imagine what the future is going to look like in terms of sea level rise, in terms of drought, flooding, other climate impacts and we need strategies in the Paris agreement to ramp up assistance to, particularly, vulnerable developing countries to build their ability to adapt and cope with what's coming at them.

An art installation that illuminated the Eiffel Tower on the eve of the climate talks in Paris called for a shift to 100% renewable energy and the protection of the world’s forests. (Photo: Yann Caradec, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Let's talk about where the negotiations are now, headed into this week where the ministers come together to find political solutions. First, what about on the question of limiting emissions, where are the sticking points now? What needs to be resolved?

MEYER: Well, there are several issues there. One is the long-term goal. What is the long-term direction we're trying to set in this agreement of where the world needs to be by mid-century in terms of emissions. That's quite a contentious issue. The science is pretty clear that we need to be well on a pathway to totally decarbonizing the global economy by midcentury if we're going to avoid the worst impacts of climate change. Another issue is how quickly we review the effectiveness of what countries have put on the table. Many of the most vulnerable countries and the nongovernmental groups have been pushing for a review no later than the end of this decade, because it's quite clear that we need to increase activities starting no later than 2020. A third issue is how you provide support for developing countries to unlock the conditional offers they've made to increase the ambition of their efforts if they have access to finance, technology, and other support, so that's being discussed. These are all tough issues but they're all key to getting the ambition package we need in the Paris agreement to deal with the gap.

CURWOOD: What about the sticking points on adaptation, what needs to be settled by these ministers?

MEYER: Well, there's a couple of issues there. One is whether developed countries in particular will commit to increase the share of their public finance support going to adaptation. Right now I think it's less than 20 percent of the total amount of climate finance provided to developing countries is on adaptation. The large share of it is for mitigation activities. So that needs to be ramped up, because, as opposed to investments in clean energy technologies and other mitigation strategies, adaptation is one area where you can't leverage private sector finance to the extent you can on something like renewable energy investments, or cleaning up a power plant, or energy efficiency and buildings. So there needs to be greater public finance. The other issue is helping countries develop the capacity to do adaptation planning and implementation. This is a tricky business that cuts across every sector in the economy, from healthcare to agriculture to coastal impacts, and it really does take well-trained infrastructure and people to deal with what they have to do on adaptation.

The Living on Earth COP21 reporting team, Steve Curwood, Helen Palmer and Emmett FitzGerald.

(Photo: Jennifer Stevens-Curwood)

CURWOOD: The president of China said it's important to have a binding agreement here, a legally binding agreement here. The United States is a little nervous about some of this language, as I understand it, because it's unlikely to ratify any new treaty brought forth by the Obama administration. How does this process thread that needle?

MEYER: Well, there's an understanding that what comes out of here next week will be a legal agreement, it will be under the Framework Convention on Climate Change that was negotiated by the first President Bush and was ratified by the U.S. Senate, so that's the law of the land, and there will be elements of it that will be legally binding. The debate in the negotiations is what are those elements and what's the language. The one that the administration has the most trouble with is one that would say that we are legally bound to achieve the 26 to 28 percent emission reduction below 2005 levels that President Obama committed to by 2025, because under the terms of the ratification agreement of the original Rio treaty with the Senate, their lawyers tell them that would require submitting the entire agreement to the Senate for an up or down vote, and we know there's nowhere near the 67 votes needed to ratify anything on climate change coming out of this meeting.

CURWOOD: Alden Meyer, Director of Strategy and Policy for the Union of Concerned Scientists. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

MEYER: Thanks, Steve. I really enjoyed it.

Links

Timeline of key events in UN effort against climate change

About Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs)

INDC submissions from nearly 160 countries

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth