Sierra Snows Ease, But Won't End California Drought

Air Date: Week of February 12, 2016

California Department of Water Resources employees ski to work at the Philips Station near Lake Tahoe. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

Californians hope two months of plenty of snow could ease the 4-year drought. But Living on Earth’s Emmett Fitzgerald reports that high snowfalls in the Sierra Mountains this winter won’t end the water problems and the state needs to manage the resource creatively and efficiently for the foreseeable future.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. This winter, the weather pattern known as El Niño has brought some much-needed rain to the parched California landscape. And even more importantly, the Sierra Nevada Mountains have gotten a lot of snow, which when it melts, should provide water to rivers and reservoirs come summer. The Sierra snowpack makes up 1/3 of California’s water supply - the rest comes from the winter storms - and many wonder if the heavy snows from December and January will provide relief from the long-standing drought. Living on Earth’s Emmett FitzGerald investigates.

[SOUNDS OF SKIING]

FITZGERALD: In green wool pants and a red jacket, Frank Gehrke skis across a snowy field at the Philips Station in the Sierra Mountains near Lake Tahoe. Frank's been doing snow pack assessments for the California Department of Water Resources for a long time.

GEHRKE: Let’s see I started in‘81 and then came up here to work for the state in‘87, so it’s been awhile.

Snowy Lake Tahoe (Photo: Reno Tahoe, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

FITZGERALD: Frank’s carrying a giant metal tube as he skis. He stops in the center of the field and plunges it into the snow.

[SOUNDS OF THE STAKES GOING INTO SNOW: SOUNDS CONTINUE]

FITZGERALD: He measures both the depth and the weight of the snow-core in order to calculate how much water is in the snowpack.

GEHRKE: We’re basically taking a core sample of the snow, then we weigh that core, you know the weight of water is well known, so it turns out that the geometry of the tube is such that an ounce of weight represents an inch of water content.]

FITZGERALD: A Tahoe local named James E Church first developed this process way back in 1909.

GEHRKE: He was a professor of romance languages I believe. [LAUGHTER]

[SOUNDS OF THE STAKES GOING INTO SNOW CONTINUE]

FITZGERALD: Frank takes measurements at 7 different sites throughout the field, to account for any variability in the ground surface. He calls out numbers to an assistant with a clipboard.

GEHRKE: 41….54

FITZGERALD: When they’ve finished with the final site Frank does some quick math.

Frank Gehrke plunges his tube into the snow pack. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

GEHRKE: So after all of that sampling we had a water content of 25.4 inches and that represents 130 percent of its average since 1966.

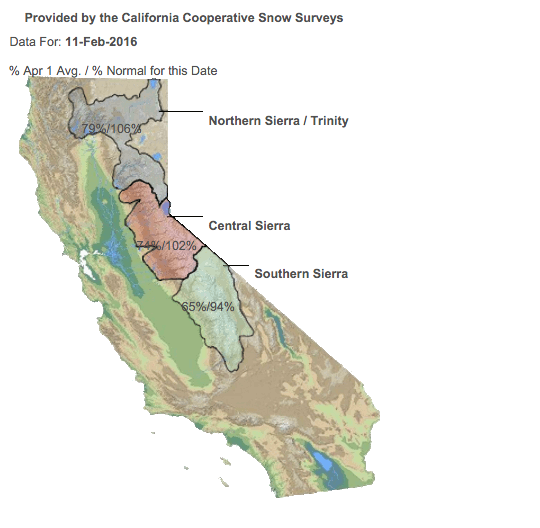

FITZGERALD: That’s 130% of the average snowpack on this day in history. Now that’s just at this one location. On the day, the snow pack across the state is lower then where we are right now, but still above average, and Gehrke is pleased.

GEHRKE: I think it’s very encouraging. It’s a really good start. We do need much better than just average, and we’re getting it now, hopefully we really increase that percent of average as we move on into the spring.

FITZGERALD: The most important test will come in April, when scientists tally up the total snow accumulation for the winter. Last April, California governor Jerry Brown came to Philips Station for the year’s final snowpack assessment. But there wasn’t any snow. Pictures of the governor standing there next to Frank on the bare grass became iconic images of the California drought. It was the worst snow year in Frank’s career. But 7 of the last ten years have had below average snowpack, and Frank says that’s a huge problem because snow in the mountains provides California with water throughout the year.

GEHRKE: The snowpack is sort of the natural reservoir. The snow accumulates up here in the Sierra during the winter and then gradually melts when we hit late spring. And if we don’t have a good snowpack than those reservoirs do not essentially recover from the releases they had made the previous summer and fall.

Examining the extruded snow core. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

[ROAD NOISE, TRAFFIC]

FITZGERALD: Back down from the mountains in sunny downtown Oakland, I stop by the Pacific Institute, a global water think tank. Peter Gleick is the director, and he says two good months of snow is an encouraging start to the winter.

GLEICK: But it says nothing about what the next couple of months are going to bring. Our wet season runs through April.

FITZGERALD: And a lot could change between now and then. In February of 2013 the Sierra snowpack was about where it is right now, but the next two months were bone dry, and snow levels ended up well below average for the year.

GLEICK: We don’t really know what’s going to happen in the next couple of months. It is an el Niño year, but el Niños can be wet for Northern California or they can be dry for Northern California. So it’s a little bit of a toss of the dice still.

Frank Gehrke measures the snow pack. (Credit: Emmett FitzGerald)

FITZGERALD: As if to illustrate that point, the week following the snowpack assessment was dry and hot, with record high temperatures throughout the State. As of recording this, the statewide snowpack has fallen to just 104% of average. Warm weather in February can also cause snow to melt earlier than usual, which is a problem for reservoir operators.

GLEICK: If it melts now, early in the season, we can capture some of it in the reservoirs, but we can’t capture it all because we have to have reserve space in our reservoirs for future storms in order to protect the state against flooding.

Snowpack percentages for February 11, 2016 compared to the average on that day. (Photo: California Department of Water Resources)

FITZGERALD: So a lot of that water content is lost. No matter what the weather brings between now and April, Peter says Californians shouldn’t be thinking that el Niño is going to pull the state out of drought.

GLEICK: Even if it’s a wet year in California, that by itself is not enough to get us out of the drought. Our reservoirs are still really low, our soil moisture is low, our groundwater is over-drafted. We’re in a deeper hole than one year is going to fill.

FITZGERALD: And State officials agree. Despite the snow, the California Water Resources Control Board recently decided to extend Governor Jerry Brown’s emergency water restrictions through October of 2016. Max Gomberg is the Climate and Conservation Manager for the control board based in the state capital, Sacramento. He says, since the governor announced the water restrictions last April, Californians in urban areas have cut their water use by 25%.

GOMBERG: It’s really a tremendous achievement. It shows that people are paying attention and care for this precious resource. Because 25% that’s one in every 4 drops of water that was used is no longer being used.

FITZGERALD: And water conservation is only going to get more important in the future. Max says that drought is a natural part of the climate in California, but climate change is making it more common and more severe.

GOMBERG: And the drought in the past 4 years in California has been so severe you know we’ve lost 22 million trees, we’ve had a tremendous number of forest fires, communities have run out of water, we’ve lost 97% of some of our fish species. The impacts have really been devastating.

FITZGERALD: Peter Gleick of the Pacific Institute says with warming temperatures and increased demands on the water supply, California may never really “get out” of the drought.

GLEICK: In a sense a drought is not having enough water to do what you want. And in that sense the Western United States one could argue is in a permanent drought. We no longer have enough water to do everything that everybody wants, at least as inefficiently as we’re doing it today. Look, if we end April with 140% of normal snowpack that would be great, but we have permanent water problems in California and in the West.

FITZGERALD: And they require permanent solutions. Peter says it’s great that the state is asking people to stop watering their lawns, and shorten their showers, but those measures are temporary, behavioral changes.

A nearby Sierra Mountain stream (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

GLEICK: I do think the state should be doing more in terms of permanent improvements in efficiency. We should be providing farmers with financial incentives to move to more efficient irrigation systems or to grow more efficient crops. We should be providing incentives for our cities to find and fix leaks, to replace inefficient washing machines and toilets and showerheads.

FITZGERALD: Increasing efficiency might seem like a small step, but it’s the best way to reduce the State’s overall water use.

GLEICK We could cut our water-use in cities by 20 or 30 percent without affecting our quality of lives. We could cut water use 15 or 20 percent in agriculture without cutting the amount of food we grow.

FITZGERALD: And Peter Gleick says we should also be getting creative and taking advantage of new supply options, like treated wastewater.

GLEICK: That stuff’s not a liability, that stuff’s an asset. And increasingly water districts are exploring ways of putting that high-quality treated wastewater to use. We’re using it on landscaping here. We’re using it for cooling power plants, we using it for all sorts of industrial processes.

FITZGERALD: These sorts of changes aren’t glamorous. But if California is going to survive and grow in the changing climate, they're exactly what’s needed.

For Living on Earth this is Emmett FitzGerald in Oakland, California.

Links

Stay up to date on the state of the California snowpack

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth