UN Climate Chief Calls for Urgent Action

Air Date: Week of April 22, 2016

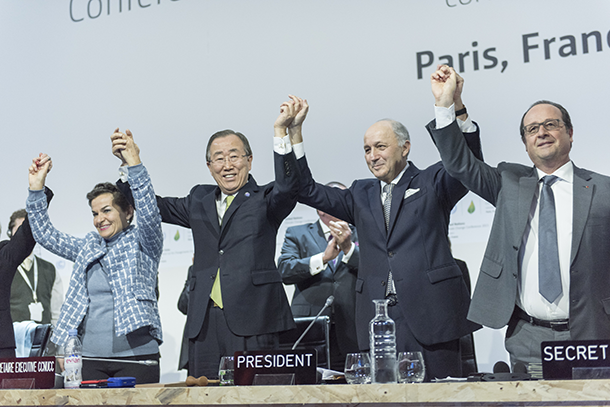

From left: Christiana Figueres, Executive Secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC); UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon; Laurent Fabius, Minister for Foreign Affairs of France and President of the UN Climate Change Conference in Paris (COP21); and François Hollande, President of France celebrate after the historic adoption of Paris Agreement on climate change. (Photo: United Nations Photo, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Earth Day 2016 brought a significant milestone for the Paris Agreement, as some 175 nations signed on at the UN Headquarters in New York City. Yet the ambitious goals of this climate agreement are not guaranteed without aggressive moves to curb carbon pollution. Host Steve Curwood sits down with Christiana Figueres, Executive Secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, to discuss what’s required to give civilization a fighting chance.

Transcript

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

To mark Earth Day, leaders and diplomats from more than 150 countries converged on the United Nations in New York to sign the Paris Climate Agreement at the opening of the yearlong window for its adoption. Back in 2014 US Secretary of State John Kerry and China’s State Councilor Yang Jiechi struck a deal to work together to make deep emissions cuts, a deal that became the main architecture of the Paris Agreement. Still, bringing in more than 180 other nations and getting the strong commitment of business leaders for the Paris negotiations wasn’t easy. Many credit the skillful, tireless diplomacy from UN Climate conference chairman and French foreign minister Laurent Fabius, and the brilliant leadership from the Executive Secretary of the UN climate process, Christiana Figueres, who was welcomed like this.

[CHEERING]

CURWOOD: At the party that some delegates, environmental and civil society activists held the night the agreement was sealed. The Living on Earth team was there. We whipped out our cellphones to record the euphoric response. And Christiana Figueres joins me again now. Welcome!

Figueres says that while the Paris Agreement is an important climate diplomacy milestone, it should have been reached about ten years ago. (Photo: UN Photo / Eskinder Debebe, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

FIGUERES: Well, thanks very much, Steve.

CURWOOD: You know the last time I saw you, you were practically crowdsurfing in this wild celebratory party in Paris. How does it feel to be a rockstar?

FIGUERES: Honestly, that last night was such a crazy night. It was a fantastic celebration. We had so many people from so many different sectors, so many different countries, all of whom were truly ecstatic, and ecstatic I think because so many people worked for so many years to get to a global agreement, and we did, and the result was in fact even more ambitious than most people thought was going to be possible. So, yeah, it was a very celebratory night.

CURWOOD: How do you feel about the Paris agreement now?

FIGUERES: A couple of thoughts. Yes, I would agree with the celebration mood that night. It was historic, it was unprecedented and truly the result of a lot of hard work from thousands and thousands if not millions of people, honestly. I also am quite happy about some of the very technical results of that allow us to now guide the transformation of the global economy toward a decarbonized society over time. So, that's the good news. The bad news honestly is that I feel that that agreement if we lived in a perfect world is actually coming too late. In a perfect world we should have come to that kind of an agreement perhaps 10 years ago. I know that it was not possible 10 years ago. We know that we weren't ready, but just from a science point of view, just from an intense vulnerability of populations point of view we're really running against the limit here, so what it has done is put a lot of pressure now on the implementation of that agreement, and again in a perfect ideal world we would have a little bit more time to implement, but now we're five minutes to 12, so the speed and scale of implementation is going to have to be pretty aggressive.

Figueres speaking at COP21 (Photo: Iga Gozdowska / WeMeanBusiness, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: When you say five minutes to 12, what are you thinking of in terms of scientific terms?

FIGUERES: What I'm thinking of is a something that is not in the Paris agreement, which is when do we actually have to get to the maximum point of emissions, which is called peaking and begin to descend. We should be peaking within this decade. We should be peaking by 2020 for one purpose, which is to protect the most vulnerable populations because peaking after that is going to mean that we have accumulate greenhouse gas concentrations that make it very very difficult for the survival or even adaption of the most vulnerable populations. Now, most vulnerable populations are in developing countries. The irony of this whole exercise is that developing countries themselves will have to make an effort for their own security and that is a tough pill to swallow right because developing countries do not have the historical responsibility, they're moving into a position of responsibility into the future but they do not have the historical responsibility and yet if developing countries do not act they are working against their own interest.

CURWOOD: Let's talk about some of the numbers in Paris. The goal, I believe, is to keep things below 2.0 degrees Centigrade rise...

The meeting hall at COP21 (Photo: Iga Gozdowska / WeMeanBusiness, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

FIGUERES: Well below, and make every effort to keep it under 1.5.

CURWOOD: How important is that?

FIGUERES: It's critical. It is truly, truly critical, and it is most critical for the most vulnerable populations. Again, you know the guiding star here is how are we going to protect the most vulnerable because these are countries and populations that are exempted of emission responsibility. That does not mean that they're exempted of action responsibilities - two different types of responsibility. And you know one of the very rays of light and hope of the Paris agreement is that every country agreed that they want to contribute even if it's in a small way. However we cannot lose sight of the fact that vulnerability and impact truly is accessed exacerbated upon some populations and if we do not get to 1.5, if we go...first of all if we go above two, Steve, I have to share with you the insurance industry has already determined that a world that goes above two degrees is uninsurable. You and I do not want to live in a world that is uninsurable and certainly the corporate world does not want to operate in a world that is uninsurable. So that's already one economic threshold. Now the human threshold is the 1.5 because what the 1.5 does...it doesn't even guarantee the survival of the most vulnerable, it gives them a fighting chance.

CURWOOD: One problem, the independently determined national commitments these INDCs, they...

FIGUERES: I'm going to finish your sentence for you, OK, they do not add up to 1.5 or two degrees.

CURWOOD: A very toasty 2.5 or more.

In some developing countries, the cost of borrowing money can be as much as three times higher than in the developed world, creating a barrier for clean energy projects like this solar thermal plant in India. (Photo: Brahma Kumaris, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

FIGUERES: 2.7 to 3 is what they have. So, what's the good news there? The good news of the INDCs is that in a world without those climate change plans we were headed for a world that would've increased forward to five and by some accounts even six degrees. Frankly, a completely unviable world.

CURWOOD: Does it matter? I mean, because if the world is uninsurable at two degrees, if it's really even a challenge for folks to survive at 1.5, once you get to three or four or five...

FIGUERES: Then what it means is it's a very unfair selection right because it is those that have the most resources to be able to afford the adaptation to those conditions that would be the ones who would have a chance, and the others who don't have those resources would have no chance. That's not the world we want to live in right? So the good news of the INDCs is that we have at least shaved off the worst scenario, the worst consequences. So that's better, but it's not where we want to be. And because we knew this ahead of the time and I had warned the press at least a year ahead, and I actually told them if any of you come and you all of a sudden have a eureka moment in Paris and say [gasps] "discovery, the INDCs do not get us to well below 2 degrees," I'm going to chop your head off because I'm telling you now a year before Paris that they do not get us there, and that is why the Paris agreement has a very very different logic to the Kyoto Protocol. The Kyoto Protocol is a static commitment that by X year you will have reduced X amount. The Paris agreement does not have that deadline. What the Paris agreement does is it establishes a process throughout which countries will increase their emission reductions and certainly their resilience. So, my guess is we're probably going to go through a 10, 15 maybe a 20 year process of constant improvement, constant increase in efforts to reduce emissions until we get to where we need to get to.

Multinational development banks can help link up the supply of capital for climate-conscious development projects with the need. In Sierra Leone, the African Development Bank is funding the NERICA project carried out by the African Rice Initiative. (Photo: R.Raman, AfricaRice, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, if we were to do a little bit of math, humanity is emitting someplace between 8 to 10 gigatons of carbon...

FIGUERES: 32 a year.

CURWOOD: 32 gigatons of carbon a year. Oh my so...

FIGUERES: I think I'm picking up your thoughts here, Steve. So here's the math. OK, we already have 2000 gigatons up there in the atmosphere right? If we want to stay under two degrees, we only have a sum total of another thousand gigatons that we can put up there. That's not for this year or for this decade or for this century. That is 1000 gigatons for as long as humans intend to stay on this planet unless we invent some other absorption of carbon methodology that we don't have yet. If we want to stay under 1.5 we only have 600 gigatons, so you do the math.

CURWOOD: Let's do the math. So roughly we have 30 years to eliminate these emissions.

FIGUERES: No we don't. We don't have 30 years. We have much less than that because if we are to take those 30 years then you are assuming that we're going to go with 32 every year and then we're going to go from 32 to 0. Well, that is not realistic. There is no way that the economy, that transportation, that energy, that agriculture can go from 32 on the 31 December of year whatever and by January we're down to zero. We have to be able to buy ourselves the time for a smooth transition.

CURWOOD: Christiana Figueres is the Executive Secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. And we'll be back in just a moment.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from Wunder Capital, an online investment platform that allows individuals to invest in solar projects across the U.S. More information and account creation at Wunder Capital.com. That's Wunder with a 'U'. Wunder Capital: do well and do good.

CURWOOD: Just ahead...why it costs many developing countries much more than the US and Europe pay to finance climate resilience. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Jacqueline Schwab, “I Heard From Heaven Today,” Down Came an Angel, traditional Georgia Sea Islands/arr.Jacqueline Schwab, Dorian Recordings]

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, and I’m Steve Curwood. We're back now with Christiana Figueres. She's Executive Secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. I want to talk more about developing countries. At the Paris meeting some folks from developing countries pointed out one of the big obstacles around finance is the interest rate of the environment, that when European and American companies go into the capital markets, they borrow at two, three, four percent, whereas, if you're in India or Cameroon, you're going to pay 12, 15 percent, and that therefore there's a tremendous advantage that the rich part of the world has over the developing world, and yet the developing world needs lots of capital resources. How do we get around that?

The Paris Agreement will be open for signing at the UN Headquarters in New York City through April 21st, 2017. (Photo: Jim, the Photographer, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

FIGUERES: In general, it's true. It's not true for every single developing country, but in general it is true that developing countries face a higher cost of capital than industrialized countries. Why is that? Because A: there is at least a perception whether it's true or not, but there's a perception of political risk, there's a perception of policy risk meaning that some countries put a policy in and then take it out, there's a currency risk, and there is what I call the risk of the unknown because a lot of capital we just don't have a long-standing tradition of investing the levels of investment that need to go in now into the developing world, right? We're getting there but it still is considered a very risky business. So from an investor point of view you can't blame them because they have to give a value to that risk. So the challenge here in bringing down the cost of capital is you need to bring other financial institutions whose bread-and-butter it is to work in our developing countries, who understand our realities and who actually have the possibility and the understanding of taking that risk off the table. So here I'm talking for example very specifically about development banks. The InterAmerican bank knows Latin America very well. The African Development Bank knows the African countries very well. They know all the quirks. They have been working there for years. It is their responsibility to actually work here and you have to be very specific to go into the INDCs that all of these countries have put on the table and work with other financial situations so that the development banks can be helpful in developing the kind of financial instruments that are necessary to buy down some of the risk and then attract foreign capital investment that can go in there at a cost of capital that is competitive.

CURWOOD: Why isn't that happening? We're facing a climate emergency, the people do need to develop a sustainable low carbon way, not much time and yet the money doesn't seem to be moving in this...

FIGUERES: I completely agree. I've come to the conclusion that we have moved from the financial crisis of 2008 to the financial emergency of 2016 and the fact is that today 2016 we see capital that has been accumulating since 2008 because there's no place to put the capital so you have an accumulation of capital over here with my left hand and with my right hand you have an enormous need for investment particularly in infrastructure both for energy generation, for transport and all of the infrastructure that is necessary for adaptation, and so you have supply and demand and they're not talking to each other yet. I am feeling a huge urgency around how do we build the bridge. Big question mark.

What the world needs now is a sense of urgency about the climate crisis, says Figueres. (Photo: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So you worked really hard on this, six years you've served as executive secretary, and you're about to leave. What's ahead for you? What you do to top this?

FIGUERES: Well, it is difficult to top honestly. It's been a true privilege and an honor to support all governments and so much of the private sector that is actually also companies as well as civil societies. It has just been a fantastic opportunity to have that breath and depth of collaboration for a true common clause, but what do I do after the 7th of July? Honestly, it's still unknown. There are many balls in the air. There are many muffins in the oven and I'm still trying to decide which of those muffins do I want to prioritize and pull out of the oven. So, stay tuned.

CURWOOD: They need a new secretary-general at the UN.

FIGUERES: Not they. We. We the population. We the people need a new secretary-general at the UN and I am actually quite happy about the fact that it does seem that there is a huge political push for that to be a woman, and I think it is about time after 70 years of the United Nations and eight secretary-generals, it's about time that there be a woman. We also know that if we followed geographic rotation, it is the turn of Eastern Europe and there are currently quite a few female candidates, some male also, but quite a few female candidates from Eastern Europe and from other regions. So we will wait and see what happens.

Christiana Figueres is the Executive Secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). She will be stepping down from the position this July. (Photo: COP PARIS, Flickr public domain)

CURWOOD: To wrap this up, so if you were in charge of all of this what you do to get this to respond to the tremendous challenges that the science tells us we have?

FIGUERES: No, I'm very happy and I think everybody is about the direction that we're moving in because we are moving incontrovertibly and unstoppably toward a decarbonized world and a more resilient world. The piece that is not there yet is the sense of urgency. The fact is that we would move toward that decarbonized society and a more resilient infrastructure globally anyway because that is already started, but what we need to do is increase the speed so I'm on a personal campaign to invite every person that I need to swallow an alarm clock and to realize that you know this is ticking inside of us. We just cannot rest on our laurels and this is not about business as usual. This is a new definition of BAU, business as urgent. So, let's swallow the alarm clock, step up to the plate, and increase the speed with which we taking all of these fantastic decision but that are not happening fast enough.

CURWOOD: Christiana Figueres is the Executive Secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. Thanks so much for taking this time with us today.

FIGUERES: Thank you very much, Steve, for the invitation to be here with you today. I really enjoyed it.

Links

About the Paris climate negotiations

USA Today: “175 Nations Sign Historic Paris Climate Deal on Earth Day”

New York Times: “Leaders Roll Up Sleeves on Climate, but Experts Say Plans Don’t Pack a Wallop”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth