The Well-Tempered City

Air Date: Week of November 11, 2016

A “well-tempered” city is one in which varying needs are met harmoniously, says Jonathan Rose. (Photo: AV Dezign, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

For affordable housing developer Jonathan Rose, J.S. Bach’s keyboard piece, the Well-Tempered Clavier is a source of inspiration. He thinks this carefully crafted, beautiful music offers a kind of model for how to best plan a city. His new book, The Well-Tempered City creates a vision for urban life in the 21st century which he discusses with host Steve Curwood, using case studies from flourishing cities around the world.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

[MUSIC: J.S.Bach: Oboe Concerto A major Recon from BWV49/169/1053. Allegro ma non tanto [Hammer/Rifkin] Pro arte digital [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UBoCR2eOOJ0&list=PLiJnN4bTWJ12aISIGJYe0m8IRkL8CacJD&index=6]

CURWOOD: Some music-lovers believe Johann Sebastian Bach created some of the most sublime works in the whole classical repertory. As a composer Bach changed and helped to define the whole language of Baroque music. He inspired many who came afterwards, and that includes urban visionary Jonathan Rose. In his latest book, "The Well-Tempered City: What Modern Science, Ancient Civilizations, and Human Nature Teach Us About the Future of Urban Life", he imagines the city as an ecological system, in need of harmony.

Jonathan Rose, welcome back to Living on Earth.

ROSE: Thank you so much. I'm happy to be here.

CURWOOD: Jonathan, the title of your book takes its cue from Bach's famous composition, "The Well-Tempered Clavier". Why did you pick this title?

Jonathan Rose’s new book, The Well-Tempered City, is now available for readers to purchase. (Photo: Courtesy of Jonathan Rose Companies)

ROSE: Well, I picked it because I love Bach's music, and one of the amazing things that Bach did with his music was he tried to imagine the architecture of the universe, and bring it to life on Earth for all of us. It's an amazing aspiration, and I believe we actually with our cities need to have very high aspirations.

[MUSIC: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HlXDJhLeShg] Performer & Album Info - 1:52:15

Bach: The Well Tempered Clavier - Book 1 BWV 846b -- C Major – Fugue]

ROSE: There was another issue, and that's the actual idea of temperament itself. About 2,500 years ago, Pythagoras, an amazing Greek mathematician, Pythagoras observed that the distance between the notes on a lyre were exactly the same proportion as the distance between the spaces between the planets, and he said this was the golden proportion, that everything should be tuned exactly that way. For the next 2,500 years, everything was tuned exactly that way, and it worked really well when you were playing an individual instrument in an individual key, but it turns out that you couldn't go from key to key to key. And, for Bach to achieve his amazing goals, he actually needed an expanded range of music to deal with. By 1700, Bach was able to compose in what was called “temperment,” which is actually finding tuning to the spaces in between perfections. It's not exactly perfect, but it's good enough, and it really allowed for amazing music. It allowed him to unleash the entire range of the keyboard to express his music, and I feel that's something we need, is vast integration that we need to do with our cities also.

[MUSIC: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HlXDJhLeShg] Performer & Album Info - 1:52:15

Bach: The Well Tempered Clavier - Book 1 BWV 846b -- C Major – Fugue]

CURWOOD: In your book, you make a number of analogies between city systems and works by biologists. How can we think of urban spaces as ecological systems?

ROSE: There's an amazing biological idea called biocomplexity, and the core of the idea is that all of nature comes from a vast and integrated gene pool. So, for example, think about human beings. We breathe in oxygen. We breathe out carbon dioxide, and trees breathe out oxygen and breathe in carbon dioxide. We all fit together. Where did all this come from? It comes from the fact that we have this common DNA. You've probably heard that human beings share 50 percent of the same DNA as a banana does, and 96 percent of the DNA as a frog. These integrate us in an amazing tapestry of life. We do not have that same integration in our cities, but if you think of a city plan as the gene pool of a city, and we can figure out how to tie all the parts together so that they actually can co-evolve together. What nature has it is so magnificent, is an amazing adaptive capacity, and what human civilization needs, what our cities need is that same adaptive capacity.

CURWOOD: So, you want to bring all these things together, and in your book you write, “Imagine a city with Singapore's social housing, Finland's public education, Austin's smart grid, the biking culture of Copenhagen, the urban food production of Hanoi,” and I could go on because you go on to list another 20, 30 cities. So I gather what you're saying is that right now too many cities do things in silos, that they just focus on one aspect whether it's housing or education or transportation, and this all needs to somehow come together.

ROSE: So, actually I'm saying two different things. First of all, in that fantastic list that you read, the point is, there are amazing things happening in cities all over the world and even more interestingly, cities are consistently learning from each other which is also really, really good. And so when I propose this idea of a magnificent and ecologically sensitive city, and people say it's impossible, then I can point and say, "Look, but if you just did what they're doing in Copenhagen, which is really great, and you're doing with they're doing in San Francisco, which is really great, and you're doing what they're doing in Seattle, you put it all together you would have solved a lot of problems.” Your second point is absolutely true about silos, that we function too much in silos and what we're learning is...So for example, if you want to solve a key part of affordable housing, you need higher density to help pay for it, and if you have higher density and you put it next to mass transit then that helps solve traffic problems and allows more space for parks and nature. And so the pieces all fit together, so we have to get out of our silo-designing, individual solutions and see we need to design integrated solutions.

Rose’s Via Verde is a green, affordable and mixed-income housing building in the South Bronx. The multiple rooftops contain community gardens, playgrounds, amphitheaters, solar panels, an orchard and even an exercise room overlooking the city. (Photo: Courtesy of Jonathan Rose Companies)

CURWOOD: So, in your book you outline some of the ways that cities can be thought of as having metabolisms. So talk to me about what constitutes the metabolism of the city and how it can contribute to social and environmental prosperity.

ROSE: A metabolism is the flow of energy and material through a system - Actually I also think information through a system - and interestingly 98 percent of the things that enter a city leave it six months later as waste. And that doesn't work when you have a population of 10 billion people and a huge demand for resources. That's a very linear system. So think, for example, in New York City, water is collected from a reservoir far north of the city and comes through big pipes that runs through our toilets and showers, etc., and it gets flushed out and it goes out into the ocean ultimately, a one-way system. So, we need to start creating circular systems, which again is just the way nature works, nature recycles endlessly. So, I looked at cities all around the world and Windhoek which is the capital of Namibia, a desert city in southern Africa, in the 80s discovered that it was beginning to grow rapidly and was going to run out of water. It hired an engineer and it built the world's first system that took its waste water, cleaned it up and turned it into its drinking water again, recycled it.

Jonathan F.P. Rose is a real estate developer who specializes in building affordable and mixed-income housing. (Photo: Courtesy of Jonathan Rose Companies)

The engineer who designed it said, “We should judge water by its quality, not by his history,” and that system's run for 40 years and never had a single accident. So in the cities, for example, in the American southwest, which are running out of water, beginning to do something like this. Now there’s a water treatment plant in the Washington, DC area that is taking the nitrogen and phosphorus, which are very polluting elements, out of the water for $100 a ton. They are selling it to fertilizer manufactures for $400 a ton, and so the waste treatment system is all of a sudden becoming a factory. They are capturing all of the methane that is coming out of the plant and using that to create energy, so all of a sudden it's become a energy generator, not only providing enough energy for itself but enough for the entire neighborhood around it. Now, imagine if we took these linear infrastructure systems and made them all circular systems. Imagine how many local jobs we could create, how much energy we could create, how many natural resources we could recycle.

CURWOOD: So, in your book you discuss the decline of the American cities in the 1970s. What was going on?

ROSE: A lot of factors were going on. First of all, jobs were moving out, first to the south. The great manufacturing union jobs which built so many middle-class lives were moving to the south and then abroad. The cities were incredibly polluted. There was not cohesive city planning. There was a lot of just disgruntlement and unrest, and the cities became more and more dangerous, and so people began to abandon and moved to the suburbs. And the more and more they moved to the suburbs, the more the cities, the very heart of them, began to hollow out, and they began to burn.

[MUSIC: Maurizio Pollini, The Well-Tempered Clavier Book 1 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8Ks9Q8AF4Do&list=RD8Ks9Q8AF4Do#t=924]

ROSE: So, what's happened is that cities are back. They are cauldrons of opportunity, They are places where people want to live. We have both young people who are coming to cities because they are bored in the suburbs and cities are where the education is, where the innovation is, where the cafés and jazz clubs and music and all that stuff. The life is in the cities and they want to be there. And, interestingly, the baby boomers are retiring and they no longer want to move to gated golf course communities, they actually want to move back to cities too for the same reasons that the young ones are moving but there's a second reason too. There's a lot of people retiring to live near their grandchildren.

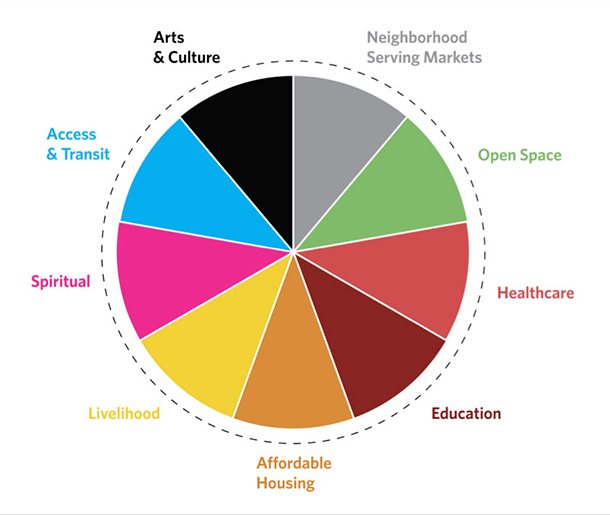

The infographic above shows the various pieces which make up a healthy, functional city and what Rose refers to as “communities of opportunity.” (Photo: Courtesy of Jonathan Rose Companies)

So there's a commencement of revitalization in cities and the issues is that's putting a great deal of demand on the housing stock, and there is not enough affordable housing for everybody who needs to live and work in cities. The answer is to create more affordable housing in cities, the only way to do that requires subsidy, and there are federal programs and there are state programs but those are not enough. Another tool cities are using to address the issue of affordable housing, what's called inclusionary zoning…They're saying if you can build market rates housing, a certain percentage of it has to be affordable and creates mixed income communities which are really healthier for people.

CURWOOD: You've, of course, done that sort of work yourself directly. We've talked in the past about your Via Verde community in the South Bronx, a place that a few years ago you mentioning that, hey, get a place in the South Bronx people would say, "What? You're nuts!", but I gather your facility is oversubscribed. What makes that place work?

ROSE: So, what make's that place work is, first of all, it's beautiful. It is extremely green. It has solar panels and great insulation, and cross ventilation. It's right near mass transit. It's right near a whole bunch of retailers, so it is walkable to many things. And then the green, it actually continues to the entire public realm so it has a children's playground on the entry level and then it has an amphitheater where all kinds of community events take place. It has an orchard that we're going to describe as going up to roofs. It then has an orchard. It has community gardens. It has on the seventh floor overlooking the whole city a fantastic exercise room, community room, so it’s really designed is an amazing place to live, and it is half affordable rental housing and half middle-income co-ops ownership housing. So it's a really wonderful integrated community.

[MUSIC: Maurizio Pollini, The Well-Tempered Clavier Book 1 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8Ks9Q8AF4Do&list=RD8Ks9Q8AF4Do#t=924]

CURWOOD: So talk to me now about the role that big data plays in making cities more efficient?

ROSE: Let's start first of all with defining what our objectives are because we're going to use big data then to make sure we're achieving our objectives. So, one of the things that is emerging is the idea of communities developing their own community health indicators. It's a list of all the things that matter to them. It can be early childhood reading rates and high school graduation rates and reducing certain climate impacts and reducing water consumption and increasing affordable housing, increasing mass transit, hundreds of items that can all be defined to reflect where a community's vision is of the truly sustainable and equitable place. Then, with big data we can measure to see where we actually are: how healthy are our families, how green are our communities, etc. And we can track this through information coming from the public health sector, coming from our cell phones coming from the internet, coming from devices all over the city, and we can see how well we were doing. We can then use the tools of city governments which are the regulations, such as building codes and zoning, investments to cities, make an infrastructure, incentives such as tax breaks. All the things that cities use, we can see, “Are we getting closer or further away from our goals?” We can keep measuring, we can keep creating a real feedback system that becomes co-evolutionary towards our objectives, just the way nature works.

CURWOOD: So you talk about the living in green spaces promotes health and well-being. How are cities trying to increase that green infrastructure?

The German musician Johann Sebastian Bach, was famous for composing in “well temperament,” the inspiration for the title of Jonathan Rose’s new book. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

ROSE: Cities actually have a lot of incentive to increase their green infrastructure. The city of Philadelphia, for example, was faced with a $10 billion mandate from the EPA to separate its water from its storm water systems, and they went back to the EPA said how about if we spend $1 billion on parks and open space, on incentivizing green roofs, and planting more street trees, and we're going to absorb the storm water before it actually goes into the sewer system, and it will save us a huge amount of money, and the EPA said, “yeah that's a great solution.” And here's what happens when you plant trees. Remember the climate is changing and it's going to get hotter. We now know that neighborhoods that have a lot of trees are 6 degrees cooler in the summer than the neighborhoods that aren't. Trees absorb pollution. Trees absorb storm water, saving cities costs and saving the outflow of polluted water into the oceans and rivers, and houses that are next to trees and streets with a lot of trees have actually higher real estate values which is good for the homeowners, but also means they pay higher taxes which is good for the city, and finally we know that when neighborhoods have a lot of trees actually the mental health of the residents is better than neighborhoods that don't have trees.

CURWOOD: So, Jonathan, what's the connection between affordable housing and community strength?

ROSE: Steve, that's a really important question. Over 20 million American families today spend more than 50 percent of their income on housing, and when you think about the additional amount of funds they have to spend on transportation getting to and from work and then childcare, it's impossible to think about how they can feed and clothe themselves, much less move forward with their lives. So, having a base of safe, green, well-located affordable housing is really critical for individual family advancement. And the goal of all this is to create what I call an "equal landscape of opportunity for all", which I really believe is the American promise. So, once you have safe, green, well-located affordable housing, you need fantastic school systems in which every child in a neighborhood as an equal chance to get ahead.

Going back to that list of cities you read in the beginning, Finland has the best school system in the world, the best school performance, and every child goes an equally good school whether they live in the wealthiest neighborhood, the poorest neighborhood, the most Finnish neighborhood or the most immigrant filled neighborhood. Every school is equal. We do not have that in the United States, and I believe that should be part of the American promise. Same thing with access to healthcare. Healthcare should be...the quality of healthcare should be equal to all. The quality of access to healthy food should be equal to all, which is one of the reasons why we are seeing this amazing community garden movement. We need access to parks and open space, we need access to multiple means of affordable transportation, we need access to arts and culture, access to great jobs, and the last thing which I think is really important is we need churches, synagogues, mosques, places of meditation, places of reflection. We live a very frantic, overstressed life these days, and we need places of retreat where we can sit back as individuals and as communities and think about our own higher purposes.

[MUSIC: Maurizio Pollini, The Well-Tempered Clavier Book 1 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8Ks9Q8AF4Do&list=RD8Ks9Q8AF4Do#t=924]

CURWOOD: Jonathan Rose's book is called "The Well-Tempered City: What Modern Science, Ancient Civilizations, and Human Nature Teach Us About the Future of Urban Life". Thanks, Johnathan.

ROSE: Steve, it's always great to be with you.

[MUSIC: Maurizio Pollini, The well-Tempered Clavier Book 1 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8Ks9Q8AF4Do&list=RD8Ks9Q8AF4Do#t=924]

Links

Living on Earth’s first story on Via Verde

Jonathan Rose Companies’ website

Harpsichord recording of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier (Book 1)

Hammond and Rifkin recording of Bach’s Oboe Concerto in A major)

Piano recording by Maurizio Pollini of the Well-Tempered Clavier (Book 1)

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth