Hog Farms and the Flu

Air Date: Week of January 6, 2017

The influenza virus is amplified in hog CAFOS (concentrated animal feeding operations) according to new research from Duke University. (Photo: James Hill, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Pigs are among animals that easily catch human influenza. New research suggests that factory farms with huge numbers of hogs close to where people live may affect the timing of the flu season. Duke University physician and infectious disease expert Paul Lantos joins host Steve Curwood to discuss his research on industrial hog farms, and how it could inform public health guidelines on annual flu inoculations.

Transcript

Now some varieties of influenza can infect both pigs and humans, and that got scientists in North Carolina to wondering if the huge hog farms in that state known as CAFOs, that is Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations, might affect flu epidemics. North Carolina is second only to Iowa in hog production with nearly nine million animals confined at any given time. So the scientists set out to investigate, led by infectious disease specialist Dr. Paul Lantos of Duke University. He is the lead author on the paper published in Clinical Infectious Diseases.

Paul, welcome to Living on Earth.

LANTOS: Thank you very much for having me.

CURWOOD: So, what exactly did your research find?

LANTOS: So, we were interested in the question of whether proximity to a swine CAFO, a CAFO in which they are raising pigs, alters the dynamics of the flu epidemic each year. In order to study this, we had to get two sources of data. One was a map of where there were swine feeding operations in North Carolina. North Carolina has the second-largest swine industry in United States with around 10 million pigs. We also needed a map of the influenza epidemic. We were able to get the map of the influenza epidemic from the state public health department. They have information on the number of cases of influenza-like illnesses recorded each week, and we got these for all 120 North Carolina counties over a four year period.

Map of hog farms in North Carolina (Photo: courtesy of Paul Lantos)

CURWOOD: And once you did that, what was the next step?

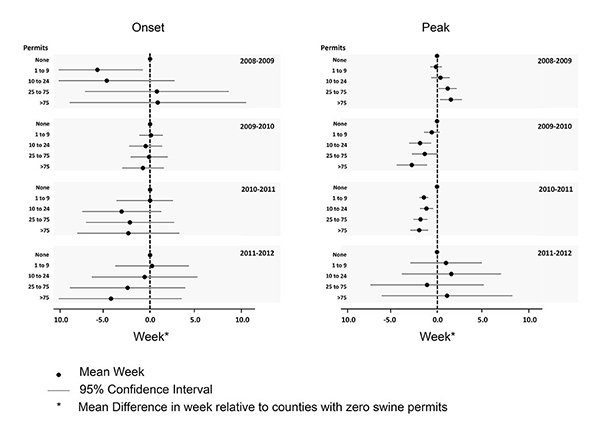

LANTOS: So, the next step was to do a statistical analysis, to see whether the timing of the flu epidemic varied as a function of proximity to the swine operations. So, we looked at the week in which the flu epidemic peaked in each county for four consecutive years and analyzed statistically whether this had anything to do with how many swine CAFOs were in each of those counties. What we found was that during 2009 - 2010 and 2010 - 2011, were for the first two years in which the H1N1 swine influenza virus was circulating, the epidemic seemed to peak earliest in counties that had the greatest number of swine CAFOs. We did not find this in 2008 - 2009 or in 2011 - 2012 which were years in which the H1N1 virus was not so predominent.

CURWOOD: So, briefly describe for me what's going on in these CAFOs that would speed up the spread of flu when it's a swine flu.

LANTOS: So, our hypothesis was that starting in 2009 this novel influenza virus, one that was never before seen in our swine industry, began to infect a large population of susceptible pigs. These pigs had no previous exposure or immunity to this virus. When the virus was brought to North Carolina, and the pigs were exposed, this very large population of susceptible animals effectively amplified the virus. So, they produced more virus just because of their sheer abundance. This probably went back to the community surrounding the CAFOs through the swine workers, and the epidemic therefore peaked faster in these communities.

CURWOOD: So, what's important about your findings in terms of decisions that people could make, in terms of public health?

LANTOS: Well, I think the most important message is that we need close cooperation between public health and the swine and for that matter the agricultural industry. We clearly have shared interest in the health of the agricultural workers and their communities, and there's importance to public health in general as well.

CURWOOD: So, if you were working with a CAFO, a Concentrated Animal Feeding Operation with pigs, what would you have your workers do to protect themselves?

LANTOS: I would certainly encourage my workers and their families to get influenza vaccinations as soon as they become available each fall, as well as getting their families and children vaccinated. That is the best tool we currently have to protect workers and citizens in general against the annual influenza virus.

We typically emphasize the importance of flu vaccination for susceptible populations, people who are likely to become very sick from the flu, so young children and people with medical problems, the elderly. We don't typically think of young, healthy, working age males being the most susceptible to severe influenza. They may not be as susceptible to severe disease, but, if they're important in the transmission of the disease, then vaccination may have an important public health effect by limiting it spread.

A key figure from the study paper showing that flu season peaked earlier in areas with more permitted swine CAFOs in the 2009-2010 and 2010-2011 (when a novel swine flu virus was most active). (Photo: courtesy of Paul Lantos)

CURWOOD: I gather that one of the characteristics of influenza is that it gets transmitted by a whole bunch of people who aren't apparently sick.

LANTOS: That's correct. People can be contagious for influenza for days before they ever develop a fever or respiratory symptoms, such as coughing or sneezing. That's what makes influeza such a daunting public health problem. People have modeled and created preparedness plans for what we do in the event of an epidemic or a pandemic, but it's very difficult to geographically contain influenza when people start traveling around.

CURWOOD: So, what do the findings of your study mean for how we need to operate these CAFOs, these Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations in the future?

LANTOS: Well, it's unclear what our findings have to offer in terms of altered practices within CAFOs. I think the CAFOs are a function of modern food production, and that will not change. So long as of a small minority our population is responsible for feeding a very large proportion of our population, there will always be very large industrial agriculture.

What we can do is increase surveillance for viruses of potential public health important within these animal populations, protect workers as well as possible, and continue trying to fund public health and research efforts to mitigate the annual flu epidemic.

CURWOOD: And, by the way, I understand that these CAFOs use a lot of antibiotics, but of course the flu is a virus which antibiotics are not effective against.

LANTOS: That is correct. Antibiotics would be inappropriate for treating influenza although we do have some antivirals that can make influenza better in people who are sick with it. It is true that antibiotics are an important part of livestock operations in the United States and throughout the world, and this may not be related to the influenza study that we just performed, but it is important in the epidemiology of drug resistant bacteria.

CURWOOD: What about vaccinating the pigs against the flu?

LANTOS: That's an interesting question. One problem with that concept is, when we develop a vaccination, we do this after having done intensive surveillance, largely among livestock throughout the world. In East Asia is an important component of virologic surveillance, and we have to anticipate what among these circulating animal viruses is likely to make a jump to humans. And then the vaccine industry develops vaccines in response to the circulating viruses. Trying to anticipate what will become predominant in pigs, then vaccinate them, is likely to be both ineffective and extremely costly.

Paul Lantos, MD is a Medical Instructor in Duke University’s Department of Medicine (Photo: courtesy of Paul Lantos)

Now, the holy grail of influenza vaccine research is the so-called universal influenza vaccine, one that will cover all strains of influenza this year, next year, and forever more, so that we get one flu vaccination and never need one again. If we could develop something like that, then perhaps vaccinating the pigs will protect them forever as well, and we could cover the human population with that vaccine as well. But this still remains a very important area of research that has yet to come to clinical practice.

CURWOOD: Dr. Paul Lantos is a medical instructor in the Department of Medicine at Duke University in North Carolina. Thanks so much for taking the time.

LANTOS: Thanks very much for having me.

Links

Dr. Lantos's study in the Oxford Journal of Clinical Infectious Diseases

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth