Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right

Air Date: Week of March 24, 2017

.jpg)

An aerial view of the sinkhole at Bayou Corne (National Nuclear Security Administration, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

A California sociologist ventured out of her liberal bubble to try to grasp why some conservatives reject government regulations in Louisiana, even as industry pollution persists - largely unchecked - for years. Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood interviewed Arlie Russell Hochschild, author of the book Strangers in their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

The present partisan divide in America has led to a number of ironies, including voters in so-called red states who seem to vote against their own best interests when it comes to regulating air quality and stream pollution. To try to understand and bridge that gap, liberal sociologist Arlie Hochschild spent five years conducting what she calls “an empathic study” of her political opposites in Louisiana for her book, “Strangers In Their Own Land.”

Arlie is a professor at the University of California, Berkeley and she joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth.

HOCHSCHILD: Well, thank you. I'm delighted to be here.

CURWOOD: So, briefly describe for me the project that this book is the result of.

HOCHSCHILD: Already five years ago I was concerned about a growing split between left and right across the country, and I realized that I lived in an enclave, a geographic enclave, a media enclave, an electronic enclave, and that we all do. So, I decided to get out of my enclave in Berkeley, California, and go as far right as Berkeley, California, is left. Take my moral and political alarm system off and try to really cross over an empathy wall.

CURWOOD: And you chose Louisiana for this project. What makes Louisiana such an ideal choice for the types of perspectives you were hoping to document?

HOCHSCHILD: I wanted to go where the right was the strongest and had grown the fastest and that was the south. Actually, when you look at the proportion of whites who voted for Barack Obama in 2012, in California it was half. In the south as a whole region, it was a third. But in Louisiana it was 14 percent, so I thought, “It's the Super South, that's perfect, that's just where I want to go”.

CURWOOD: It would seem, these people who lost their neighborhood, much of a way of life should be interested in the federal government trying to clean things up, but it's exactly the opposite. Why?

Arlie Hochschild’s newest book is a sociological investigation of the American right. (Photo: The New Press)

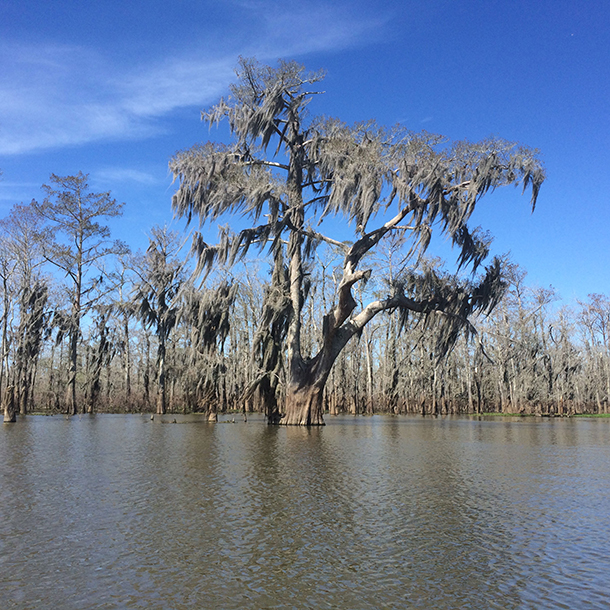

HOCHSCHILD: Well, let me just say to begin with that the people I came to meet love the birds, and they love the water and they love the grand Cypress trees, these queens of the wetlands. They love nature, and it wasn't that they didn't know about the pollution. Yes, of course, they did. Louisiana has the second highest death rate from cancer for men.

So, I think there were three things. They felt that the federal government, that was the north, and it was always wagging its moral finger at the south, and they felt that environmentalists were, you know, the last in a series of northerners coming down to tell them the right thing to do.

I think the next most important reason they distrusted the federal government is their experience with protective agencies in the state of Louisiana, and they thought, “Gosh, these are a lot of people we pay taxes to but they don't really protect us”. And they are right, because Louisiana is an oil state - that was a big discovery for me - and it outsources, in a way, the moral dirty work to the state. So, the state actually pretends to protect the citizenry from hazardous waste and pollution of air and water and ground, but it doesn't actually protect it very much. It gives out permits, as one Tea Party person said "like candy". So, they felt the federal government is just a bigger, badder version of the state government which isn't protecting us. So, they'd had bad experience. They’d been burned, and I think that's the second kind of source of resistance to the government. But the third is that they saw the government as an instrument of what I'll call 'the line cutters.'

Arlie Hochschild and Bayou Corne resident Mike Schaff. (Photo: Arlie Hochschild)

CURWOOD: This “line cutters” concept is really a fascinating one in your book. Stop for a moment and tell me exactly what do you mean by “line cutters,” and why people in the south...although I imagine anybody listening to us probably doesn't really like the notion of somebody coming in front of them if they're waiting for something.

HOCHSCHILD: The right deep story is this. You're waiting in line for the American dream. It’s as in a pilgrimage, looking at the top of the hill at which stands this much desired American dream, and you're not in the back of the line, but it hasn't moved for many, many years. Some people I interviewed hadn't gotten a raise in two decades. So, your feet are getting tired. You feel like you don't bear grudges to any particular group. You're a good person. You've worked hard. You've played by the rules, and you deserve the prize at the top of the hill.

Then, you see some people that seem to you to be cutting in line. Well, who are they? They are blacks, who now through federally mandated, affirmative action program, have access to jobs that used to be reserved for whites. Even worse, women who through federally mandated affirmative action now have access to jobs that used to be available only to men. And then you have immigrants, and then you have refugees. So, all these intruders.

And then, another moment of the right's deep story. Barack Obama, supervisor of this line seems to be waving to the line cutters. In fact, you know, isn't he sponsoring these line cutters, and isn't he a line cutter? Many people said to me, “How did a single mother, his mother, pay for a very expensive education at Harvard and Columbia. Something fishy”. So, they felt that he too wasn't obeying by the rules.

CURWOOD: Arlie, you don't talk much about race in your book. In the south, no matter how bad things were, you could look back and say well the blacks have it worse, the Negroes have it worse. So, it seems that part of this distrust of government may come from this change, this loss of comfort that, well, no matter how tough it is for poor white folks, that there are poor black folks behind them, and that comfort goes away or is going away.

In 2014, Bayou Corne was -- for the most part – devoid of its residents. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

HOCHSCHILD: Right. They don't think of themselves as racist, are insulted to turn on the television and see that they are seen this way. One man told me, “Oh, it's only the liberals that think we are more racist than they are”. And many people said, “Look, racism isn't gone by a long shot in this country, but we're not the only ones”. And race was, of course, an enormous part of the story and I do talk about it in the book, but it was woven together with the sense of decline and fear and sense of being invisible to the authorities.

CURWOOD: Now, among other instances of industrial pollution that your book discusses, Arlie, you deal with the sinkhole that appeared in Louisiana in 2012. It formed in a Cypress grove just outside of a town called Bayou Corne. The cavern was created by a collapsed underground salt dome cavern operated by Texas Pride, a company that was there extracting sodium chloride, salt, for plastic production. Hundreds had to be evacuated from their homes, and it was only in 2016 that the mandatory evacuation order was lifted. Now, Emmett FitzGerald reported for Living on Earth from Bayou Corne in 2013. Let's listen to an excerpt from one of his pieces where he met with residents who were worried about the danger of explosive gas collection in the cavern.

FITZGERALD: Jennifer Gregoire, living on Sauce Picante decided to live with that risk. She says she doesn't have much of a choice.

GREGOIRE: I understand the dangers and the risk I'm putting my family in, but it's cheaper and it's easier. I can't afford to buy nothing else.

FITZGERALD: The Gregoires are only about 20 families left in Bayou Corn. If a car drives down Sauce Picante today, it's likely either tourists or looters. Jennifer says it's no longer a good place to raise a family.

GREGOIRE: My son just had a birthday. We can’t [SOUND OF GREGOIRE CRYING], we couldn't throw a party for him this year at the house. That was bad. Nobody wants to come here.

CURWOOD: That's Bayou Corne mother Jennifer Gregoire in Emmett Fitzgerald's story. Now, in your research into Bayou Corne and the Bayou Corne sinkhold, you spoke with Bayou Corne resident Mike Schaff. Now, Schaff loses a lot, but why does he continue to oppose federal environmental regulations and in spite of his own self-professed desire to protect the environment?

High levels of hydrogen sulfide were detected at a Texas Brine Company well near the sinkhole back in 2012. (Photo: Arlie Hochschild)

HOCHSCHILD: Yes, You know it's poignant because the first thing Mike told me is, "You know the problem with federal government is, it takes community away. It supplants community. We ought to do for each other the things that government does for us. We're better off if we have local type community."

But it wasn't the presence of government that took a community away from Mike Schaff. It was the absence of government regulation that took community away from Mike Schaff, and when we talked about that later on a fishing trip and, more recently, I brought my son who is a California environmentalist, a member of the Energy Commission in charge of renewables – so, a progressive Democrat just the opposite of Mike - and we went out fishing, the three of us. And I said, "Look I'm going to hold the tape recorder, but I'd like us to get together and tell me, is there common ground on how to prevent another Bayou Corne sinkhold from ever happening in America"?

And they went to it, and they did come up with some common ground. And Mike, very hesitant to call for regulation, he had been so exposed to a bad model of government, and he'd spoken out at one after another after another meeting to deaf ears, and he feared that the federal EPA was as bad as the Louisiana one. And yet when David said, 'Yeah, but what else are we going to do here? And there is a possibility of good government. Look, over in California we have a much more tight regulation and less pollution, and you could have it too.' And when he put it that way, Mike said, 'Well, it's not fair that some states are the polluted states and have the worst health. We should live in the United States where every state has the same degree of health and cleanness of the environment.'

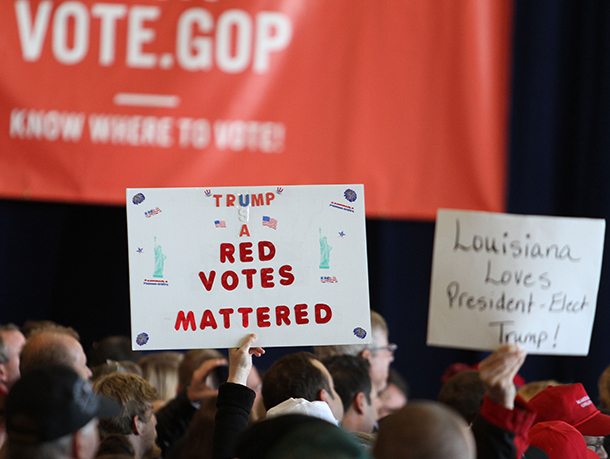

Strong support in Southern conservative strongholds was key for Trump’s presidential victory. (Photo: Tammy Anthony Baker, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, the common theme of your book is, these folks who really have been given the short end of the environmental stick, and you kind of divide them – You’re a sociologist - so you have sort of three categories of folks that you talk to. I think the one category you call “the team players.” Another you call “the believers” or “the worshipers,” and then you have a category that you call “the cowboys.” Who are these people and what influences their Tea Party politics in the face of environmental, well, really, environmental dysfunction and environmental degradation?

HOCHSCHILD: The team player is a person who says, “I am fundamentally conservative Republican, and whatever conservative Republican leadership is telling us is the right thing to do. I'm on board for that, and I'm going to be loyal to this team, my team”.

The second would be the worshiper, and here are people who say, “You know, you can't always get what you want”. And I met people who loved the environment, who knew about it in great detail. It hurt them to see a child go swimming in a lake that they knew was polluted, so it's not that they had inured themselves to a love of nature. No, but they felt like they had to renounce that love and in a way say, “Look, pollution is the sacrifice we make for capitalism.

And the third would be the cowboy. The cowboy very differently from that says, “You can't afford to love nature”. What he does is say, “Look, I'm tough. You're tough. Mother Nature's tough. We're all tough, and she can take it. Mother Nature will recover. I won't be hurt. You won't be hurt”. Each of them takes pride at a different moment, takes honor from a different emotional moment in their heart.

CURWOOD: Arlie, drill down a bit for me on one of these. Particularly, what role does Christianity play in how the far right thinks about environmental regulation? Those people who look to fundamental Christianity.

The Cypress tree is the iconic state tree of Louisiana. (Photo: Arlie Hochschild)

HOCHSCHILD: Yes, many of the traditional leaders of the Evangelical church have put a great distance between their faith and protection of the environment so that environmentalists are seen as almost animists, you know, that worship the Earth instead of God, but there's a growing group of Evangelicals who have embraced the idea of creature care and that this is God's creation, and we must protect it for posterity. And they do it with, again, a different set of meanings. There are people, a group of Christians for saving mountain tops, but it's for the sake of the unborn child, so it's got a different take.

CURWOOD: You know, recent statistics show that the life expectancy of white working-class people is declining in this country. How might this be tied to the appeal of the Tea Party to folks who are nonetheless suffering some substantial environmental outrages?

HOCHSCHILD: Yes, you're right, declining, and there's a higher rate of suicide and drug abuse and alcohol abuse. It's a despair. It's a sign of despair, actually. It's almost like what happened to black men, what hit black men earlier. It's hitting blue-collar, white men now, or the fear of it, that the decline of jobs - automation being a major cause of that - is terrifying.

CURWOOD: You spent many hours in conversation with Donald Trump supporters. You did the end of your research just as the election was approaching last year. How does Donald Trump's rhetoric on environmental issues appeal to these folks on the Tea Party right? Or is there something else about what he says that appeals over the environment and other matters?

Arlie Russell Hochschild is a Professor of Sociology at the University of California, Berkeley. (Photo: University of California Berkeley)

HOCHSCHILD: You have it right the second way. They don't love him for selecting Pruitt who's now going to cut the EPA by a quarter of its staff and undermine the Clean Air and Clean Water Act. No, but they do like the whole idea of a candidate who seems to recognize them. They almost felt like a minority group. Even though they're a majority, they felt that way. I think of Donald Trump as an antidepressant. You know, you see anger, but in the title of my book there's also mourning. You know, anger and mourning on the American right.

CURWOOD: Arlie Russell Hochschild is a sociology professor at the University of California, Berkeley. Her book is called "Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right". Thanks for taking the time with me today.

HOCHSCHILD: It's been a great pleasure.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth