The Goldman Winners 2017

Air Date: Week of April 28, 2017

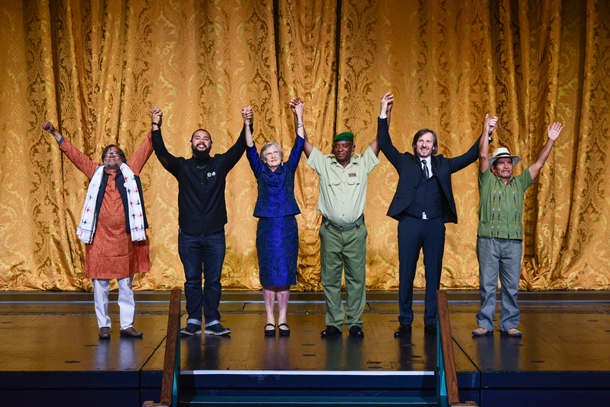

All six Goldman Environmental Prize winners onstage at the 2017 ceremony. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

They call the award the Green Nobel; each year, the Goldman Environmental Prize celebrates the achievements of grassroots activists from each major continent. Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood speaks with two of the six 2017 winners, mark! Lopez who took on pollution from a lead smelter in East Los Angeles, and 83 year old grandmother Wendy Bowman who fights strip coal mining destruction in her native Australia.

Transcript

CURWOOD: From PRI, and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Around the globe people are putting their lives on the line to protect the environment, and the Goldman Environmental Prize honors an activist from each of the six inhabited continents. Some recipients have paid the ultimate price for their work. 2015 winner Berta Caceres of Honduras and Mexico’s Isidro Baldenegro Lopez, who won in 2005, were both murdered last year.

The winners this year are no less courageous. Prafula Samantara of India, Rodrigue Ketembe, a park ranger from Congo, and Rodrigo Tot, a native Q’eqchi from Guatemala all halted mines in their tracks, while Slovenian Farmer Uros Macerl derailed plans for a toxic waste incinerator—all in the face of ferocious opposition. In a few minutes, we’ll hear from 83-year-old Wendy Bowman who battled coal strip mining in Australia. But first we turn to 32-year-old mark! Lopez who fought an Exide smelter in East Los Angeles. mark!, welcome to Living on Earth.

LOPEZ: Thank you. Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: So, tell me. Who in your community alerted you to the Exide Corporation battery acid recycling plant pollution, and when did you decide to do something about this?

LOPEZ: Yeah, you know, it was actually my grandmother who alerted me. After I graduated from UC Santa Cruz, I went to visit her and my grandpa and she actually handed me a public notice about Exide and was like, "Hey, you know Exide's still there, right?" and she was asking if I know it's still there because her and my mother actually toured the Exide site in the 90s, and you know of course, Exide was telling them all there's nothing to worry about, you know, it's nothing to worry about. So, my grandma said, "Well, if there's nothing to worry about then why did the Cal EPA staff put on all this protective gear and why did they make me put on this protective gear if there's nothing to worry about, and then more importantly, why aren't any of the workers putting on protective gear?" I think that was a signal that if the company is putting their own workers at risk, then they have no problem compromising the health of our communities. So, when I came back from Santa Cruz, she handed me that notice and said, you know, "Get on it."

Prafulla Samantara of India was awarded the 2017 Goldman Prize for combatting mining on indigenous land. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: So, mark!, tell me. What's the scale of lead contamination that's a problem in LA?

LOPEZ: Yeah, so Exide spewed about seven million pounds of lead into the air, and we're talking about over 100,000 people impacted in east LA and southeast LA. And so, there's absolutely no level of lead that is safe in our bodies, especially in children, and so it affects brain development which impacts educational attainment which of course impacts the future of our communities, but it also affects impulse control, and so exposure to lead in communities has been correlated with rates of violence and crime in communities, and so these are things our communities have been plagued with, and so we have to ask the question:“What role has Exide played in this?”

CURWOOD: Now, what did you and your community find especially challenging in dealing with this type of contamination there?

LOPEZ: One of the hardest parts was actually dealing with the state. The state allowed Exide to operate without a permit for years, and so they're a responsible party in this disaster, right, and so every step of the way they've stalled, they've told us that things couldn't happen or what we wanted was not possible. They told us that the problem was not that big, it's just these two homes we need to clean, and we had to push them to 40 homes, then 80 homes, and 209 homes and now we're over 10,000 homes that the state is acknowledging are impacted by Exide. And that's not even the half of it. They're only looking at 1.7 miles radius around the Exide site, but state Department of Health data was released that showed that up to 4.5 mile radius around the site, there's a higher level of lead in children's blood than the rest of LA County.

Slovenian Uroš Macerl took over his family farm and embarked on a five-year struggle to reverse decades of air pollution that had impacted the town’s wildlife, domesticated animals, and people. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: Now, California's famous for, or I guess some would say, infamous, for being environmentally proactive, but it sounds like your experience is the opposite, that you’ve had to drag the California government kicking and screaming to deal with the lead smelter problem in East LA. Why do you think that is?

LOPEZ: Yeah, you know, I think the state likes to posture itself as somehow different from the rest of the country, of course, with Trump in office now as leading the resistance to the Trump agenda, but the reality is when you think about environmental racism, it exists in East LA and it exists in all parts of LA. It exists in San Diego and Coachella Valley, it exists in the central coast and in the Central Valley in the Bay Area. Environmental racism exists.

Guatemalan Q’eqchi’ leader Rodrigo Tot worked for more than 30 years to secure land titles for Q’eqchi territories. His efforts have indefinitely deferred nickel mining in two villages. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: Tell me about the lead acid battery recycling act of last year, 2016, and the income and fees that it's expected to produce.

LOPEZ: Yes, I think you're referring to Assemblywoman Christina Garcia's bill AB 2153 that is a battery fee bill, and so this fee that's being charged for batteries that actually just started this month will be collected and will create a revenue stream that's estimated at $30 to $40 million a year to help clean up this Exide issue and also 14 other sites across the state of California where they are dealing with lead smelter issues. And they call these ghost smelters because the company no longer exists, and so there is no responsible party, and so this bill is really helping to kind of relieve these issues in communities where there's no other solution in sight.

CURWOOD: So, when you came back from college and worked to close that lead battery smelter, that recycling plant, it sounds like that was just the beginning.

Rodrigue Katembo is a ranger at Virunga National Park and the Goldman Prize winner from Africa. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

LOPEZ: Yeah, I mean it's interesting, right, because it took something like two decades to shut down the facility, and I think something that's important to note is that I'm third generation in my family fighting against Exide, but all of the work that our community has put in has made it so that my babies aren't the fourth generation having to fight against Exide, right, and that's really significant.

CURWOOD: How do you think the rest of America is responding to the lead contamination crisis?

LOPEZ: I'm really hoping that this Exide issue and the Goldman award is helping to raise the visibility around lead as a crisis that's facing the country. This doesn't happen with a million people marching in DC or even a million people marching in downtown LA. It starts with neighbors talking to each other, saying,“Hey, this is messed up right? You agree too? Let's talk to our other neighbor... it's messed up right?... OK you agree?”... OK you got a couple neighbors on that block, then you can advance on the next block... and you got that block, and you got a neighborhood, and you got that neighborhood and you can get a couple of neighborhoods and start a movement, right? I think our fundamental questions that we try to answer are: what is it, how does it affect us, and what can we do about it? And if you got answers to those questions, then you can start a movement in any community.

Lopez is the third generation in a family of activists. His grandparents (front) are well-known community-activists in East Los Angeles. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: mark! Lopez is one of the 2017 Goldman Environmental Prize recipients. Congratulations, again, mark!.

LOPEZ: Thank you, Steve. It was a pleasure talking to you.

CURWOOD: Joining us now is Wendy Bowman of Australia. Coal mining in Australia goes back 150 years or so, but when strip mining began near her farm in New South Wales, environmental and health concerns turned Wendy Bowman into an activist.

BOWMAN: It was all underground mining, very small in the early days. There didn't appear to be any big problems for a good 150 years, then all of a sudden in about the early-to-mid 1980s, open cut mining started, and the government was letting out -- just putting leases all over the place, and people were getting shocked that their country was in a lease area, and that was the start of all the problems because the mining people were very abusive and argumentative and they told you exactly what we had to do, and so we decided that it was our land, and we would tell them what they could do.

CURWOOD: So, when and why did you found MineWatch NSW, I guess that stands for New South Wales. What's the mission?

North American winner mark! Lopez accepting his Goldman Prize at the ceremony. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

BOWMAN: Well, what we did with MineWatch in the beginning, because nobody knew their rights or whatever, we started this group and we found a lawyer and a valuer who both knew New South Wales Coalmining Act very well, so they were able to come to our meetings, explain to everybody what their rights were. So, we helped people doing all this. I mean, there were a lot of small farmers that did not understand these great big environmental impacts statements that the mines would dump at their house and say, "Read that". It was about three encyclopedias big, and so many of them used to ring me up and say, "My God, I can't read all of this," and I would say to them, "Just look at the chapters. You read the chapters that are worrying you, such as noise, dust, water, whatever," and that was basically what MineWatch did to help people.

CURWOOD: So, what kinds of contamination has resulted from the mining?

BOWMAN: Well, the water. That is one of the big problems, and we've only very recently discovered that the contamination is a lot worse than we thought. Now, we've only just discovered that about 40 or 50 kilometers or miles away from Newcastle, the silt at the bottom of the Hunter River is jet black. Now, we have not had time to get it tested, but we believe that is a result of the water slowing down and everything being left and that is the latest big worry, but prior to that, all our creeks in the rivers, the water was so clean and beautiful. You could see all the rocks in the bottom of the water. You could see the fish, the turtles, and we had platypus in all the rivers. There's none left.

CURWOOD: The platypus is gone, huh?

BOWMAN: Anywhere where there's been mining, mine water being allowed to go down the river or the creek, there's no more platypus.

Wendy Bowman is one of the last residents left in Camberwell, a small village that bore the brunt of coal mining pollution in New South Wales. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: What kind of pollution-related health impacts are you seeing among people who are near these mining operations?

BOWMAN: For years, the blasting at the mines was so big that we had this orange cloud so thick you could hardly see your own back gate, and that covered all your roof, it covered everything, and we found when we owned the farm next door to this open cut mine that all that dust landed on the crops that the dairy cows had to eat. They would walk in after a blast and walk back out again, they would not eat it, and so this was the big problem, the dust. And so, nowadays, we have worked with the New South Wales Mineral Council, the blasts have gone right down to what they used to be. They're not allowed to blast if there is a wind blowing, etcetera, etcetera. They have to be very careful. Then we started – in Singleton we started the Singletonshire Healthy Environment Group because we heard that so many people had respiratory problems like asthma and that sort of thing, and when you see lots of little children coughing and spluttering... I know young teenagers that are so bad with their asthma that they have oxygen at home, but sometimes that's not enough, so their mother's got to race them -- it takes a half an hour to drive into town to the hospital where they've got the bigger oxygen things and they can stay there overnight.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about how you'll continue to oppose the negative and environmental health impacts of coal mining in Australia. What's next?

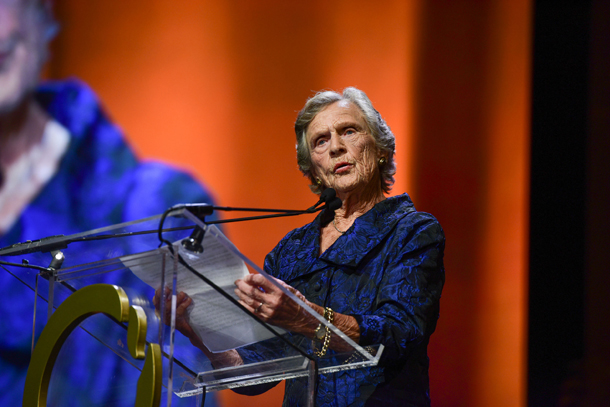

Bowman giving her acceptance speech. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

BOWMAN: Well, we haven't gotten very far with the health problems just recently. The government just doesn't want to seem to know anything about it. For years now, we have been asking... every time there's a new mine or an extension to a mine, we have said there must be a health assessment added to the environmental impact statement, and the government will not do it. And we've been asking this, I'd say, for at least 15 or 16 years. They won't do it. So, I think the more people like us say something, they're going to have to start thinking about it.

CURWOOD: Wendy Bowman is a Goldman Prize recipient and founder of MineWatch New South Wales. Thank you so much for taking the time today, and congratulations!

BOWMAN: Thank you. It's been a pleasure speaking to you.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth