The Traveler’s Guide to Space

Air Date: Week of April 28, 2017

The SpaceX Dragon cargo craft. (Photo: NASA Johnson, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

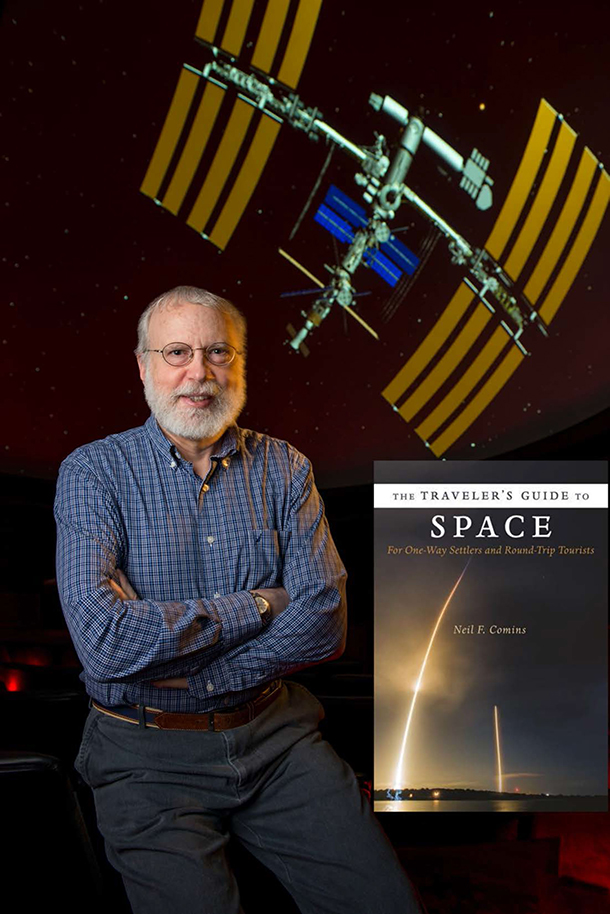

Humanity’s adventure in space is more than half a century old, and soon anyone with enough money may take a trip beyond the atmosphere. They’ll need a guide book and now there is one that supplies both tourists and scientists with a field manual. Called “The Traveler’s Guide to Space: For One-Way Settlers and Round-Trip Tourists,” author Neil Comins, a professor of physics and astronomy at the University of Maine, tells host Steve Curwood that adventurous travellers will experience wonders as well as considerable discomfort and danger.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Humans have been leaving the planet to travel in space for more than 50 years, but only a handful of people who aren’t scientists or test pilots have had the privilege so far. Well, that’s about to change with Elon Musk’s Space X program. He plans to send space tourists around the moon in 2018, and he’s promised to go eventually to Mars. So if you are thinking a bit about space tourism – say orbiting the Earth or the moon or even taking the big trip to Mars, there is now a book for you. "The Traveler’s Guide to Space: For One-Way Settlers and Round-Trip Tourists" is part Fodor’s guide and part textbook. It gives the reader a well-researched handbook for interplanetary travel, covering aspects of space travel to interest the inexperienced tourist as well as the research scientist. The author, Neil F. Comins, comes by his expertise honestly. He teaches physics and astronomy at the University of Maine at Orono. Welcome to Living on Earth, Professor Comins.

COMINS: Thank you. Pleasure to be here.

CURWOOD: So, what do you think the biggest challenge is going to be for first-time space travelers?

COMINS: Well, it depends on how long they're up there, and then depending on where you go, adjusting to the changes in your body in space, really profound.

CURWOOD: What do you mean changes profound? What kind of things do you go through?

Neil Comins, professor of physics and astronomy at the University of Maine, authored The Traveler’s Guide to Space. (Photo: Neil Comins)

COMINS: Well, for example, [LAUGHS] if you've ever seen the police stop somebody for being intoxicated, they will run them through some tests and one of the tests they do, for example, is to have them stretch their arms out and then put their finger - index finger say - on their nose. And it's something that when we're normally working, living on earth and not drunk, we can do just fine. When you go into space you lose that ability. So, one of the first things you have to do, and you're taught about this before you go, one of the first things that you have to do is to re-coordinate your muscles. So, if you are, for example, going to reach out and press a button, say, the chances are in the normal scheme of things when you first go into space you're either going to mash your finger into the button or miss it entirely because your muscles don't know what to do. So that’s an example of one of the things.

Another thing that happens as soon as you get into space is the fluids in your body start changing, and the reason for that is that, well, you don't need your legs very much anymore, and they don't need the blood supply that they're getting because you're not using them. And so your body literally starts redistributing the fluids inside it, and you physically start changing, your legs get spindly, your face gets puffy, and you have to adjust. It takes several days for your body to adjust, get the fluids where they should be -- mostly out of your body.

CURWOOD: When I get excited about a new destination and go get a guidebook about that place, one of the first things to do is to look at the restaurant and food options, but in your book no such luck. Why is that?

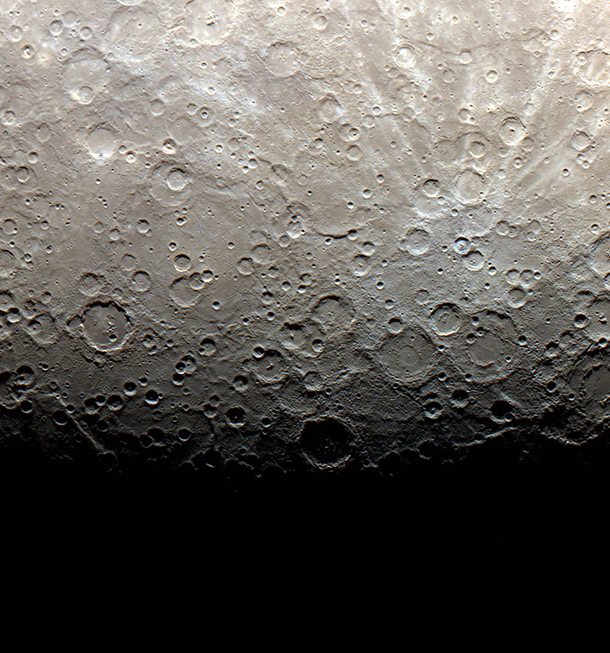

On Mercury, three days are equivalent to two years; in other words, the planet spins around its axis three times for every two orbits around the Sun. (Photo: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

COMINS: Well, it's even worse than no such luck. It turns out that when people get into space, our sense of taste diminishes. Things that would be spicy to us here on Earth can be almost tasteless. The best that they can do is provide much spicier foods than you normally would tolerate here on Earth to compensate for that, and if there's good news to go along with this, the art of making food for space has come a long, long way from the days where it was pressed out of tubes, for example. Things are getting better as far as foods are concerned, but as we say in Maine, we ain't there yet.

CURWOOD: Now, if someone is interested in venturing into space, say, they want to write one of those big checks to Elon Musk who’s saying he’s going to take people there, what sort of questions should they ask themselves first?

COMINS: Well, that's an excellent question. There are lots of things: number one, are you willing to put up with the preparation that goes into it, and that can be, depending on who you fly with, and where you're going, that can be up to a few years. For example, the cosmonauts when they prepare they have four to five years worth of preparation. It won't be that long if you're going on a short flight, suborbital flight which means up and back but not into orbit, or to the space station six months or a year perhaps depending on, again, who you're flying with, but it really is a matter of getting your mind wrapped around it, number one. And then there are things like what are you going to do when you're there? And perhaps the most important thing to realize if you're going to space is that when you come back you're going to be a different person.

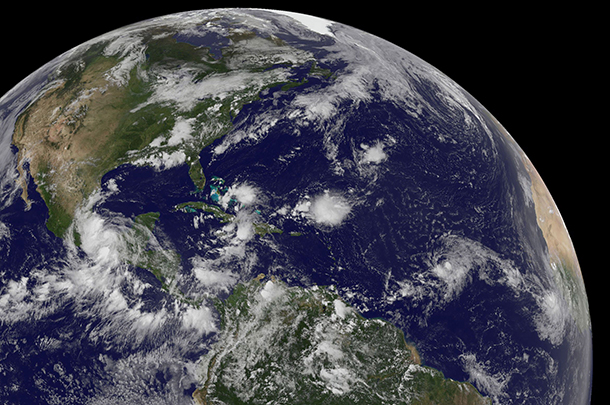

There is a room in the International Space Station (ISS) where one can view a full half of Earth at a time – so in 90 minutes, the time it takes the ISS to orbit the Earth, an observer there would see the entire surface of our planet. (Photo: Rob Gutro / NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: How so?

COMINS: Well, suppose you were to leave your family for, say, six months and go to Europe, and do things that number one, you haven't ever done before, and no one else in your family is doing or has done, and you see the world differently because you’ve been, say, to the mountain tops, and you're coming back home with a perspective about the Earth and your life and your relationship to the Earth that is different than when you left. Adjusting to how you are different when you come back from space compared to your family and friends is incredibly important to understand, and so working to realize that and be ready for that, very important.

CURWOOD: So, talk to me about the joys of traveling in space. What is there to see and do?

COMINS: Oh, lots of wonderful things. Again, it really depends on where you go, but one of the most popular things that all the astronauts I've ever talked to say is to look at the Earth. There is a room on the International Space Station where they can sit and look at the Earth as -- as a whole to see half of the Earth at any given time and watch it. They can sit there for a long time because it takes 90 minutes for the space station to go around the Earth. So, if you sat and watched the Earth from space for 90 minutes, you would see the day side, the night side, and every inch of your surface sailing by over your head, and that apparently gives astronauts great satisfaction.

The Moon may soon become a tourist attraction for the travelers who are looking for extraterrestrial experiences. But according to Comins, the Moon needs some basic amenities before you book your flight. (Photo: NASA, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

Another possibility of fun things to do is if you go to another world, say, our moon or the moons of Mars, or space debris like comets or asteroids in our neighborhood, the travelling on those worlds is going to be a spectacular experience. If you go to the moon, by the way, by the time you get there I expect that the places where the Apollo astronauts landed will be international regions where you are not allowed to go so you don't mess things up, but other than that, traveling around the moon and exploring it and literally for many, many people going there in the near future, you may well explore parts of the world like the moon that no one has ever been on before.

CURWOOD: What about gender? How well are men suited for long-distance space travel and perhaps settling on another planet, and how well are women suited for that? Obviously, we need both in our species.

COMINS: Yes, of course, that's really important. One of the big issues related to gender is the fact that in space we are much less protected from radiation than we are here on Earth, and that radiation coming from the sun, coming from the other stars and also particles, that's all stopped by the Earth's atmosphere, but it is virtually impossible to build a spacecraft that will protect the people going in to space, say to Mars. So, the point is that if a woman was to go to Mars and the eggs in her body were left there, the eggs that she would use to reproduce, say, were left there, then the chances of them being damaged are extremely high.

The two galaxies visible in this Hubble image are called NGC 4424 (the larger one) and LEDA 213994 (the smaller, brighter one below). Comins says the space traveler will be able to see views like this in person and may even be able to visit them in the not-so-distant future. (Photo: ESA/Hubble & NASA, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

So, what they would have women do is to have the eggs that they would want fertilized, removed, possibly even fertilized, before they leave Earth, and then put in really well protected carrying cases if you will, so that in principle when they get there and if they want to have children then -- also on Mars, I might add, the radiation is very dangerous, so they would want to gestate, to have the children living underground, for the most part, to protect those fetuses from radiation.

CURWOOD: Doesn't all that radiation though affect the testes, affect the sperm as they are being created? Male or female, if you go and get an X-ray at your doctor’s office, they put that little lead coat on you.

COMINS: You're absolutely right, and I honestly don't know if NASA has a complete set of data at this point, but it would not it would not be a good idea to fertilize an egg in space. In other words, sex, that's one thing, but fertilizing eggs in space could be damaging, because, as you said, the sperm could be damaged. However, the good news is that when the men get to a world and are protected from the radiation, say, underground on Mars, then it may be the case -- one can only hope -- it may be the case that the -- the sperm that are then generated after they have been protected from the radiation could be normal, not damaged, and then they could in principle, reproduce.

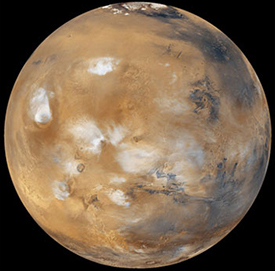

Though there are great risks involved in the colonization of Mars, Comins believes that it is inevitable and it will be the next great leap for humans. (Photo: NASA, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, you say that there could be some really dire kinds of mistakes in space travel. What are you talking about?

COMINS: There are events that are out of people's control. Impacts happen all the time from particles in space. I'll give you an example. One atom of iron. Iron is a heavy element, but one atom is in the normal scheme of things almost undetectable here on Earth. One atom of iron traveling space at the normal speed of atoms in space... when it hits a spacecraft or a person, whatever, has the impact of a baseball thrown at a hundred miles an hour.

CURWOOD: Ouch!

COMINS: Yeah, it can ruin your whole day. Then if this one essential thing that is taken out into space to, say, put onto a spacecraft going to Mars and it floats away, then you got a serious problem. So, that's another example of the kinds of things that can happen and, in fact, do happen. And equipment fails... there's always going to be back-ups in triplicate likely, and that's going to help deal with these kinds of problems and likewise computers fail so they've got to be backed up as well.

CURWOOD: Now, somebody listening to us might say, wait a second, why go settle on Mars when we've got a perfectly good planet here as long as we keep it perfectly good.

COMINS: That's a fair question. I think that going to Mars and settling there could besides forcing us to develop the technologies to do so would enable us to have a culture, a group of people who are living together in completely different circumstances then anything on Earth, and they could potentially, in the best of all possible worlds, they could potentially provide us with an understanding of how people can interact and survive and thrive, that we could perhaps eventually use to model societies here on Earth, and I think that would be something that would be something that would be invaluable when it to comes to pass.

Pictured here is the Discovery shuttle’s final launch from the Kennedy Space Center in 2011. Private ventures like SpaceX and Virgin Galactic are dramatically changing and propelling forward space travel, by opening it up to citizens who are willing to pay. (Photo: NASA/Goddard/Rebecca Roth, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Neil, before you go, I wondered if you could read from your book for us. It's the beginning of chapter 10, Emigrating to Mars or Returning to Earth.

COMINS: Here we go. Colonizing Mars will create a new society of humans that is likely to identify itself as different to humans on Earth. Establishing colonies are Mars will be the hardest, most expensive, most dangerous, and most transformative emigration experience in history. Every aspect of human society will have to be modified or reinvented, including agriculture, water collection and purification, mining, manufacturing, construction, transportation, communication, medicine, reproduction, social activities, cultures, religions, education, economy, emergency responses, recreation, policing, alcohol production and protection from radiation to name a few. The first tier of needs that humans will have for survival in a long-term colony on Mars include access to safe liquid water, breathable air, food and protection from radiation from space. However, none of these things is available on the surface of the red planet today, nor will any be in the foreseeable future.

CURWOOD: So, it sounds to me like you think this will be the big leap for humanity. This will be the biggest change so far that we go through.

COMINS: That we've gone through so far, I absolutely believe that. Yes, discovering new continents was a major change, and developing technologies that we could use to make life better was a major change. But unless and until we discover life, intelligent advanced life elsewhere in our neighborhood of the universe, our going out and becoming the advanced life on another world, that's big.

CURWOOD: By the way, in your book, you don't have a handbook for what do you do if you do run into other intelligence in the universe if you're out there. Lonely Planet has a section to tell you what to deal with hassles and opportunities, but your book doesn't have anything like that.

COMINS: No, but as soon as it happens, I promise I will write that.

CURWOOD: Neil Comins' book is called "The Traveler’s Guide to Space: For One-Way Settlers and Round-Trip Tourists". Thanks so much for taking time with me today.

COMINS: My pleasure. Thank you for having me.

Links

The Telegraph: “NASA announces alien life could be thriving on Saturn’s moon Enceladus”

Space.com: “Some ‘Tatooine’ Alien Planets May Be Able to Support Life”

Gizmodo: “SpaceX Wants You to Start Saving for Your (Possibly Deadly) Trip to Mars

Fortune: “SpaceX and NASA Are Looking for Places to Land on Mars”

ArsTechnica: “The Journey to Mars has a price tag, and it will give Congress sticker shock”

Science Times: “Mars Moon Exploration Project: France & Japan Aim To Land Probe”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth