India, Coke, and Pepsi

Air Date: Week of June 2, 2017

Coke and Pepsi are ubiquitous in Tamil Nadu food and beverage shops. (Photo: courtesy of Keith Schneider)

As the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu struggles through its worst drought in 140 years, citizens are fighting Coca-Cola and PepsiCo bottling plants that tap into already scarce clean groundwater supplies. They create jobs but are seen as outsiders profiting from India’s resources. Keith Schneider, senior editor for on-line news site Circle of Blue, tells host Steve Curwood about the struggle for water between foreigners and citizens.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Drought is also a perennial problem in parts of India, especially in the south, and now the state of Tamil Nadu is experiencing its worst drought in 140 years. While citizens struggle to meet their daily water needs, the American-branded beverage companies Coke and Pepsi have become a focus of concern.

Keith Schneider is Senior Editor and Chief Correspondent at the environmental news website Circle of Blue and has reported on this struggle for water. Keith Schneider, welcome back to Living on Earth.

SCHNEIDER: It’s nice to be back. Thank you, Steve.

CURWOOD: So, tell me -- where is Tamil Nadu? What's it like in the big city there, Chennai, right?

SCHNEIDER: Chennai, which is a metropolitan area of 10 million people and the fourth-largest metropolitan region in India. Tamil Nadu, in southern India in a state of 78 million people and over 1,000 kilometers of coastline on the Bay of Bengal, has had tremendous threats from ecological disturbances and meteorological disruptions over the last several years.

CURWOOD: What's the problem now with the drought?

SCHNEIDER: Chennai and Tamil Nadu have episodic droughts every year because there are two monsoons or were two monsoons, one in the fall and one in the late spring. And between those monsoons and typically in other years there were dry years, and those dry years are now extending and in this case for two years. So, the drought is crippling industrial companies. It's become a serious impediment to the quality life all over Tamil Nadu ... long water lines, municipalities are shutting off water to their customers weekly now, in some cases. Water is not something that is taken for granted at any time by anybody in Tamil Nadu.

CURWOOD: So, talk to me about the history of Coke and Pepsi in this now very dry region.

SCHNEIDER: Well, Pepsi Cola and Coca-Cola had been active in India up until 1970 when the industry was nationalized, and they left. Pepsi came back in 1989 to establish a new plant, and Coca-Cola followed in 1991, and things were relatively peaceful until 2002.

Lines to refill water containers, like this one in Tamil Nadu, have been common in recent months. (Photo: courtesy of Keith Schneider)

Coca-Cola built a plant in Kerala, a southern Indian state that borders Tamil Nadu, and during a drought and farmers and their wives protested and blocked the entrance to the plant and said that Coca-Cola had no sort of moral authority to be privatizing scarce water resources, and this is water that they thought was being taken from their crops, and they protested and the state of Kerala totally shut the plant down in 2004, and it never opened.

And it sort of opened up this moral threat -- that Indian residents found a moral threat from American-branded companies to take water, privatize what they viewed as a public resource, and it has spread. Since 2014, there have been six plants -- Coca-Cola and Pepsi plants that have been shutdown -- and there is very significant public support for being very tough on these American-branded bottlers.

CURWOOD: And remind us, these are American intellectual property rights to brand Coke or Pepsi, but how much of this is actually owned locally by Indians?

SCHNEIDER: Most of the plants are owned locally by Indian bottlers. Coca-Cola has, as of 2015, 57 bottling plants -- it has less now because they closed three last year. And Pepsi in 2015 had 37 plants, most of them owned by Indian families.

CURWOOD: So, what's the argument of Pepsi, and Coke as well, as to why they should be allowed to the harvest this water?

SCHNEIDER: One interesting thing here is that neither Coke nor Pepsi would answer my questions like that. So, I can suggest what they would say, based on my reporting, and what they might is one, they have a right to this water just like any industry in Tamil Nadu has a right -- smelters use water, tannerys use water, beer makers use water, why should Coke and Pepsi be singled out not to be able to take advantage of a resource that's so essential to their product line? Two, that Coke would argue that in taking this water that it's going to replace every drop that it takes somewhere in Tamil Nadu as part of its global water conservation program. And three, they would say that they’re a private company, or public companies that have a right to make money off what they do, which is to make drinks. And the last piece they would say is that they are employers, so they have good jobs in nonpolluting plants -- these plants don't pollute very heavily -- in a state in which good jobs that are in nonpolluting industries are necessary.

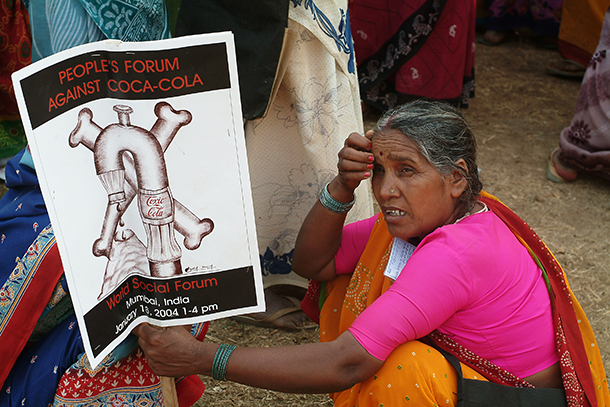

Protests have resulted in Coca-Cola and Pepsi plants shutting down, but citizens continue to organize as more plants are built. (Photo: Knut-Erik Helle, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: And the flipside and the argument is, “Wait, this the public's water, and now you are going to take it, privatize it, put a profit in it when the situation is desperate. This is outrageous.”

SCHNEIDER: Well, the American bottling issue in Tamil Nadu is interesting to me because on the one hand, an American-branded company taking water, privatizing water for their private gain. But at same time, Tamil Nadu residents say almost nothing about the extensive pollution in their rivers, the industrial pollution by Indian plants and the lack of sewage treatment. So rivers in Tamil Nadu as in much of the West, are filthy.

So, there's this bifurcated debate. On one side, the American companies are easy targets for social activism around privatizing water and what is viewed as a foreign intrusion in their culture, and on the other side there's very little comment on the extensive water pollution which actually is ruining much more water than what the bottled water is taking from rivers and groundwater in Tamil Nadu.

CURWOOD: So, I take it at the end of the day this issue is more about environment versus profits and outsiders versus natives.

SCHNEIDER: That's a big piece of it, and the other piece of it is that in India -- rural India in particular -- the idea that big companies, big foreign companies can just descend on these areas with their major plants and do as they wish -- that era over.

CURWOOD: Why are Coke and Pepsi so determined to get into these markets?

SCHNEIDER: Well, Coke and Pepsi are multi-billion dollar companies that need to expand their markets, and in the West, sales of Coca-Cola and Pepsi are descending, are diminishing and the business plan for both companies was to expand principally in Asia. It's not working very well, despite multimillion dollar marketing campaigns and both companies have initiated some pretty significant water conservation measures. Coke uses less water than it ever did before, and it says it's replenishing every drop that it uses. This hasn't convinced its critics.

Keith Schneider is senior editor and chief correspondent at Circle of Blue. (Photo: courtesy of Keith Schneider)

CURWOOD: So, the protesters here have been successful at being able to shut down some of these plants in the past few years. Look the future. What do you expect to see happening ahead?

SCHNEIDER: Um, I think Coke and Pepsi are going to have trouble, I really do, because water is becoming much more scarce around the world. Groundwater in Chennai is an asset that is closely watched now because a good deal of it is polluted, so the clean water is seen as a valuable natural resource to be protected, and that wraps into this whole Coke and Pepsi thing because they’re, they're tapping clean water, clean groundwater, not polluted groundwater. So, they're seen as tapping the best that Tamil Nadu has to offer in its water resources, which plays into this resistance that private companies are privatizing a public resource.

CURWOOD: So, Keith, how much of an example to activists here in United States is the resistance to Coke and Pepsi there in India?

SCHNEIDER: Well, civil resistance in India looks much different than civil resistance in the United States. People can gather very quickly in India to protest. There seems to be much more flexibility in their schedules to be able to protest, and they’ll stick at it for weeks and weeks and weeks and weeks at a time. In Kerala, where the first Coca-Cola resistance began around a plant, those protests lasted a year. People showed up at the plant gates every morning by the hundreds for well over a year before the district decided to act, and the state shut the plant down.

Very impressive to watch an Indian protest, the way it built over the week from a tiny protest and how it spread, working in the institutions of the various associations, the business associations, the teachers' unions. It was amazing how it just built and built and built into this tremendously joyous festival of cultural grievance.

CURWOOD: Well, Keith, I want to thank you for taking the time with me today. Keith Schneider is Senior Editor and Chief Correspondent at the environmental news website Circle of Blue. Thanks so much.

SCHNEIDER: Thank you, Steve.

Links

Circle of Blue: “The Right to Life and Water: Drought and Turmoil for Coke and Pepsi in Tamil Nadu”

Straits Times: “Drought grips southern India, set to worsen in summer”

Circle of Blue: “In City Prone to Drought, Chennai’s Water Packagers Rush In”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth