Obesity and House Dust

Air Date: Week of July 14, 2017

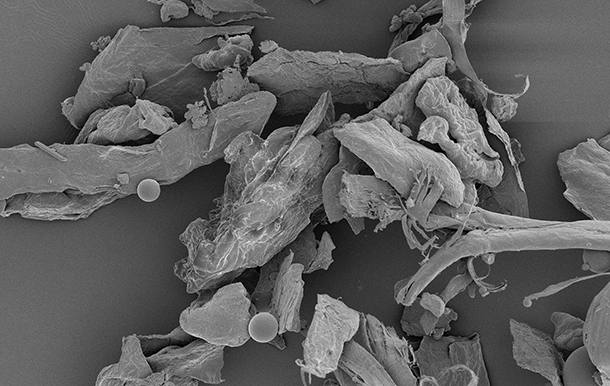

House dust under high magnification. (Photo: NIAID, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

Certain hormones at times tell our bodies whether or not to create fat cells, and hormone disrupting chemicals can confuse those messages. Such chemicals are found in chemicals such as pesticides, flame retardants, and plastics. They also turn up in house dust, and new research from Duke University found that typical amounts of household dust spurred the growth of mouse fat cells in a lab dish. Study author Chris Kassotis and host Steve Curwood talked about the implications for human health, and children’s development, given America’s obesity epidemic and how we might stay healthy in our own homes.

Transcript

CURWOOD: All that house dust that seems to lurk in the corners of our homes, particularly under the beds might not worry you too much, unless you’re a stickler for spotless surfaces. But new research from Duke University might have you reaching for the vacuum because what’s in that dust is hardly benign, and the irony is cleaning products like triclosan are part of the problem. Chris Kassotis, a postdoctoral research fellow at Duke’s Nicholas School for the Environment, discovered the dust contains traces of hormone disrupting chemicals such as triclosan. And in his experiments ordinary house dust spurred the growth of fat cells in a lab dish. Many common products -- plastics, flame retardants, and pesticides as well as triclosan -- are known to affect hormones, as well as neurological, reproductive, and immune functions.

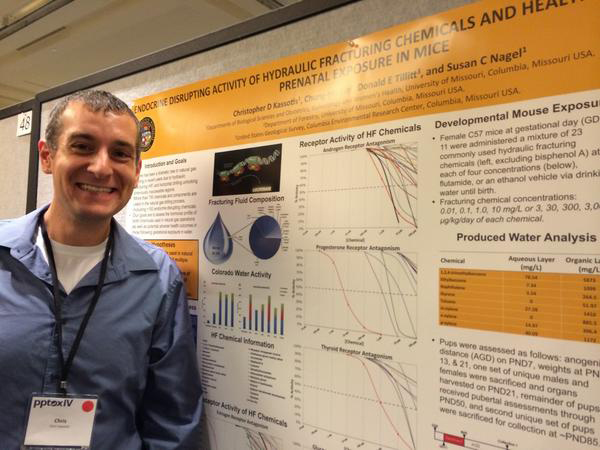

Chris Kassotis co-authored the study published in the journal Environmental Science and Technology. Welcome to Living on Earth, Chris.

KASSOTIS: Hi. Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: Chris, I was just amazed to see that your study says, essentially, I could be getting fat because I'm exposed to household dust, and the last time I looked, well, my housekeeping isn't perfect. There is dust there. How did you come to the notion that, wow, household dust could be making people fat?

KASSOTIS: Yes, it's a great question, and it's an important point. So, we definitely are not saying that house dust will make people fat. This is a preliminary step in that pathway. So, first, we're showing that house dust can stimulate the development of fat cells in the lab.

CURWOOD: But, wait a second. Doesn't that raise the specter that, at the end of the day, that therefore it could be making me fat?

KASSOTIS: So, it is testing that mechanism; however, it's a little too early to say that it would act the same way in an animal or ultimately in a human.

CURWOOD: So, talk to me some about the methodology of this study and describe what you did to test how these dust samples, in fact, seemed to simulate fat cells.

KASSOTIS: So, yes, in this study we used a mouse fat cell line. So, these are essentially fat precursor cells. If we think about the development of any differentiated or final cell type, like a bone cell or a fat cell in the body, these are fully developed cells. So, this cell model is cells that are committed to become fat cells at some point in time. They can't develop into any other cell type at this point, but, without some sort of further push, they're going to sit in their early state and not take on the characteristics of what we think of as a mature fat cell.

However, if they get that push, which we can give them by exposing them to some of these environmental contaminants, over the course of two weeks in the lab they then undergo a series of changes. So, they become more spherical in shape, and they start to accumulate lipid into the cell. Ultimately what we do is, we measure the lipid content of these cells, and then we also measure the number of these cells, and we found that these various contaminants can both increase the lipid content, we would think of this is a rough proxy for fat cell size, and they can also increase the number of cells which can create a larger pool for recruiting mature fat cells.

Adipose tissue containing fat cells. (Photo: RachelHermosillo, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Larger, rounder...sounds like fat. [LAUGHS] Sounds fatty, anyway. How big a deal is your study? What's the breakthrough here?

KASSOTIS: So, I think the interesting thing for me is that exposure to an environmentally relevant mixture, which is house dust at very low levels, caused the development of fat cells in the lab, and, when I say very low levels, what we're talking about is the Environmental Protection Agency estimates that a child consumes about 50 mg of dust per day which is a very small amount, but the level of dust that spurred fat cell development in our study was 10,000 times lower than that. So, while there isn't a direct translation from a concentration that we use in this model to a dose that a child eats, the magnitude of that difference is concerning to us.

CURWOOD: Chris, you've got me scared. I mean, if I don't run the HEPA vacuum cleaner at my house, and a very young person comes through, it sounds like I could very well be putting them at risk of a lifetime of obesity. You don't know that yet, but that's the suspicion.

KASSOTIS: So, I will say that there are still a lot of gaps in our understanding of this topic, and there isn't a good understanding at this moment as to what level of exposure to a certain chemical results in a health effect. So, it's far too early to say that, you know, someone visiting your house would receive exposure to a chemical, and that would result in some sort of health effect.

What we normally tell people is, if you're concerned, there's plenty of steps that can be taken to reduce exposure to these chemicals. So, one of the things that we often tell people is that dusting frequently is a good way to reduce exposure. With that said, we suspect that dry dusting may just actually kick these chemicals back up in the air and make it easier to inhale them. So, it really should be a wet dusting to avoid increasing your exposure to these chemicals.

CURWOOD: So, a fat kid might say, “It's not my fault. It's not the soft drinks or the potato chips. It is the fact that my parents, well, they didn't clean the house as often as they might have.”

KASSOTIS: Well, ultimately we don't know enough to say whether that's going to be a contributory factor in humans, certainly. What I can say is that we do have some compelling studies in animals where they have exposed an animal during gestation. So, while they're still in the mother and then controlled for food intake and controlled for exercise and monitored weight gain, and the animals exposed to the chemical gained more weight than the animals that weren't, suggesting that it's not just about exercise, and it’s not just about the amount of food you eat. The exposure to that chemical may have reprogrammed your metabolism in some way, such that your body handles nutrients and calories differently than other people or other animals because that work has all been done with animals.

Chris Kassotis is a researcher at Duke University. (Photo: courtesy of Chris Kassotis)

CURWOOD: So, what comes next in terms of this research?

KASSOTIS: So, I think two things stand out to me. The first is seeing if rodents, you know mice or rats exposed to house dust probably via their diet, in some way show some sort of metabolic risk or disruption, whether that's weight gain or some other outcome that we can measure. The second thing is looking for an association with humans. So, that's going to take a larger study with a lot more house dust, and we commonly talk about children being the most sensitive to exposures of this type, so it may be you really have to look at young adults or children and their metabolic health to find any sort of connection.

CURWOOD: Chris Kassotis is a postdoc research fellow at the Nicholas School for the Environment at Duke University. Chris, thanks so much for taking the time today.

KASSOTIS: Thanks so much for your interest.

Links

Environmental Science & Technology: The study on house dust and fat cell growth

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth