How to Save Most Species: Part 2

Air Date: Week of July 21, 2017

Above, a wildlife bridge helps critters safely cross the Trans-Canada Highway near Banff, so that their habitats are connected. E.O. Wilson calls for an extensive, connected network of ecosystems to be reserved for nature in North America – he calls it, “Squaring America.” (Photo: WikiPedant, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

Within decades Earth may lose as many as 50% of the species currently living on our planet. To avert ecological disaster, renowned conservationist and Harvard Professor E.O. Wilson has proposed a radical idea in his book Half-Earth: to set aside half of Earth’s land and sea for nature. He believes that this could save 80% of the species and preserve ecosystems. Host Steve Curwood spoke with E.O. Wilson to learn why the 87-year-old ecologist is optimistic about the role of technology to help with this mission.

Transcript

CURWOOD: We’re back now with renowned conservationist E. O. Wilson, whose recent book "Half-Earth" proposes a daring idea. He says we need to set aside half of the Earth’s land and sea for the 10 million other known species on the planet. To reach that ambitious goal, Professor Wilson imagined how we might conserve so much North American land.

WILSON: I have a notion I call "squaring America”, North America, including the United States. We start Yukon to Yellowstone. That can be done right now, but let's go on. Yellowstone on down to the Rocky Mountains, and we could easily -- well relatively easily -- set up reserves all the way down there as a continuation of the corridor. We get to the southern Rockies, and then we have to jump over a bit to the Sky Island Mountains of Arizona. If we wanted, then we can continue the corridor -- if our Mexican neighbors would like it -- in the Sierra Madre Occidental. And we now go back up to the Yukon, and let us think of a great, broad corridor across the coniferous forest the height of Canada.

Then, reaching the Atlantic coast, let's bring it down through the best-forested areas to Maine and over to the still wild areas of Vermont, New Hampshire, through surprisingly open areas that remain in upstate New York until we arrive at the Adirondacks. Now, we continue the square down onto the southern Appalachians which reaches then to northern Georgia and Alabama.

But now comes the Gulf Coast. We would like to see a corridor from at least as far east as Tallahassee, extending along the Gulf Coast, which is biologically the richest part of North America, incidentally, in numbers of species. It extends on over to Louisiana and Eastern Texas.

E.O. Wilson says his “moonshot” idea to conserve half of the land and half of the sea for nature is the best shot we’ve got at saving 80% of the species now living on Earth. (Photo: Louis Raphael, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

That then, if you think about it, would box America, north, south, east, west, on our square. By the time you pull that off, if you can, you've really added a large amount of natural area.

CURWOOD: So, what is it about us humans that a majority of people don't share your view, don't understand your urgency, your sense of urgency about this? What is it about us as a species that you think gets in the way? And you write about this some in your book "Half-Earth.”

WILSON: I'm afraid that's part of what we call human nature. I believe the reasons why we do so many stupid things, including having constant war and tribal battles and internecine civic strife and conflict between religious faith, we succeeded as a species. You know, we were just one species out of many creatures that look a little like us, anyway, the Australopithecus and pre-human species. There were quite a few that came into existence and died off, and our stock was the one that got hold of the capacities for language and dividing labors of cooperating groups. We were the one species that got out from Africa, and we did it about 65,000 years ago, and our populations, our ancestral populations everywhere as they spread, and of course as they multiplied in Africa itself, they would enter whole new environments, natural environments, and everywhere they went they met the pristine environments and they found survival by utilizing everything they could get their hands on in that pristine environment.

They began by killing off, in many cases, the native birds and mammals for food. They then cleaned out a lot of the environment with the plant environment by harvesting. They began to develop agriculture -- That began about 12,000 years ago -- and that meant just spoiling the original environment. We survived. We multiplied. We were Darwinian. Those among us who did the most damage to the environment to our benefit were the ones who typically got ahead of the competitors in the next area over, and surely that has had an effect on the evolution of human rapaciousness when it comes to dealing with environment. That's why it makes it so hard to say, “Please halt and reconsider before you mow down that rainforest. Please consider leaving enough space on the surface of the Earth and the sea for those estimated 10 million other species that exist, and which we are wiping out at a rapid rate.” We don't know what we're doing, and we're destroying something ineffably beautiful and something the human mind and emotions need. Because we still have a deep love of the natural environment which we evolved and that included the richness of life and the beauty of open unspoiled areas.

Most ecosystems on Earth have been impacted by non-native species that humans have either inadvertently or intentionally transplanted. The paperbark tree (Melaleuca quinquenervia) is native to Australia but is now present on all main Hawaiian Islands and the mainland U.S. (Photo: Rose Braverman, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Why do humans need other creatures? I mean, to what extent are they just nice for us to see or how vital are they for our survival?

WILSON: When you start reducing ecosystems by allowing species to go to extinction, then what you were doing is weakening the system as a whole, and then it becomes vulnerable to accelerating change and collapse. We're worried now with good reason about climate change and the fact that we are racing toward almost lethal conditions for life as a whole if we continue on our present path, but what's less recognized is that the same thing exists for biodiversity, and the variety of life that make up the natural ecosystems in the world. We're moving toward a point where the whole thing could begin to unravel with disastrous results for people locally and globally.

CURWOOD: So, some folks would say, “Look, why not novel ecosystems, those that gradually emerge when alien species invade natural ecosystems? They might be good enough.”

WILSON: Oh, you say that so convincingly. [LAUGHS] I know you're posing the question. Well, we were talking earlier about the Anthropocene, and I told you the stunning fallacies they engage in. This is the next one. They said, “Well, all around the world, humans around the world are carrying, whether they intend to or not, these alien species, and they’re releasing them, and these are in the worst most disturbed areas that sort of building up little ecosystems of their own. These are highly unstable, and they also include some of the worst pests for humans, and of course they’re very bad for the native species that come in contact with. Novel ecosystems are something to resist and not think of ever as a substitute for a far richer and more stable natural environment. If you want an example of a serious novel ecosystem, go to Hawaii. When you get off the plane, when you get your lei around your neck, you will probably not have a single native plant species in there. There will be species of plants -- some of them beautiful -- that have taken hold in Hawaii and that can be seen at almost any port of call around the tropical world. The birds you see are all going to be introduced birds. So, what you're seeing, then, is a hodgepodge of alien species from all around, and we don't want that to be the condition of the world.

CURWOOD: So, one of the things you're write about this book is having a Lord God moment as a naturalist. Tell me what you mean by that, and your favorite Lord God moment.

The distinctive, now-extinct ivory-billed woodpecker, origin of the phrase “Lord God Bird”. (Photo: satragon, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

WILSON: OK. Well, the Lord God moment comes from the southern name for Lord God bird. The Ivory-Billed Woodpecker never was very abundant, so that southerners, settling across the south, would occasionally see one. And when they first saw one -- the second-biggest woodpecker in the world, you know, brilliantly colored -- well, when they first saw the birds, people often said something like, "Lord, God, what is that?" And that spread enough so that many of them called it a Lord God bird.

And what can I say? I have had many Lord God moments, but mostly with ants. One such moment was in the tropical forest when I first saw a swarm of army ants, up to millions in one colony marching as a broad front like a conquering army spreading through the forest floor capturing everything it could find and kill for their food and then settling back into a heavily guarded bivouac where they live. That should be a Lord God moment for anybody to see that.

CURWOOD: Of course, the Ivory-billed Woodpecker is gone. You can't find it any more.

WILSON: It's gone. And the last one was seen, I think, in the early 1940s by a little boy who knew where a single Ivory-Billed Woodpecker would rest for a while, and he would go out to see it, and then one day that was gone, and all hunts for it have failed. I would have given anything to be able to see an Ivory-Billed Woodpecker.

CURWOOD: You have a name for the geologic epoch we may be creating here if we continue on the path of destroying habitat and causing species extinction. What is this name and tell me why you call it that?

WILSON: Well, you know, about the time of the name Anthropocene, the Age of Man, came in, I suggested that we use the term for this period that we dominate the world as the Eremozoic. Eremo means lonely. So Eremozoic means the Age of Loneliness. And for me, kind of the saddest part of all, there would be a heavy weight on the human soul if we really entered it, would be the Eremozoic, the Age of Loneliness where most of life on Earth that we evolved in, most that you and I are still living in, was gone forever.

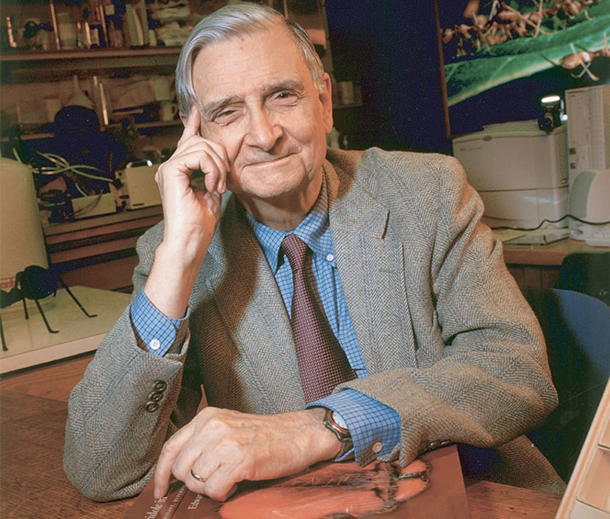

E.O. Wilson in his office at Harvard surrounded by images of the ants he studies as a myrmecologist. (Photo: Jim Harrison, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.5)

CURWOOD: And maybe our planet, our species, shouldn't try doing without the other species, huh?

WILSON: I think we shouldn't try that. We only have one – I like to call it, “One Earth, one experiment.” We've only got one shot at this. Let's be careful.

CURWOOD: I know that you're especially optimistic about the role that technology could play in conserving biological diversity? Why do you think the digital revolution is going to help nature rather than make things worse?

WILSON: You know, the first reaction to thinking about digital civilization we're moving into so dramatically right now is going to be bad for the natural environment. That's because we think about the digital revolution in the same terms that actually did exist leading up to it, but the digital revolution has qualities to it that are not shared, by any means, with the first primitive technological industrial revolution, and those qualities all point to a lessened size of what's called the ecological footprint. And everyone, I think, should know what the ecological footprint is because it's critical.

Ecological footprint is the amount of area – of space if you wish to make it three-dimensional -- required by the average person to maintain for that one person all of the necessities of life. That ranges from food to water to shelter to entertainment to governance and on and on and on. And for most of the world it's one to 10 acres depending on the country. For America, it's much higher than anybody else, and it's not sustainable.

And why would I be optimistic that the digital world is going to shrink that? That is the nature of economic evolution, that people want and they will select if they have any choice, instruments and material goods that are smaller, consume less energy and material, need to be fixed less frequently and all of that means that the ecological footprint is destined to shrink. If we can now keep our hands off of the natural areas in the world, if we can devise entertainment and fulfillment making use of all of the accouterments and monuments of digital age and develop a conservation ethic, I envision a possible paradise for humanity by the 22nd century.

CURWOOD: Paradise for humanity by the 22nd century, and right now we're threatened by climate change, pollution, and loss of species at a precipitate rate?

WILSON: Well, I know. But now let's think about the United States over a comparable period. The development of the nation as a society from, say, 1800 to 1900, humans are making that rate of change, and I believe there's an inevitability of the shrinking of the ecological footprint, not because people know what it is and want to see it shrink, but because of the economic evolution that seems inevitable.

CURWOOD: E. O. Wilson’s new book is called “Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life.” Thank you so much, Professor Wilson.

WILSON: Thank you for the opportunity.

Links

E. O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth