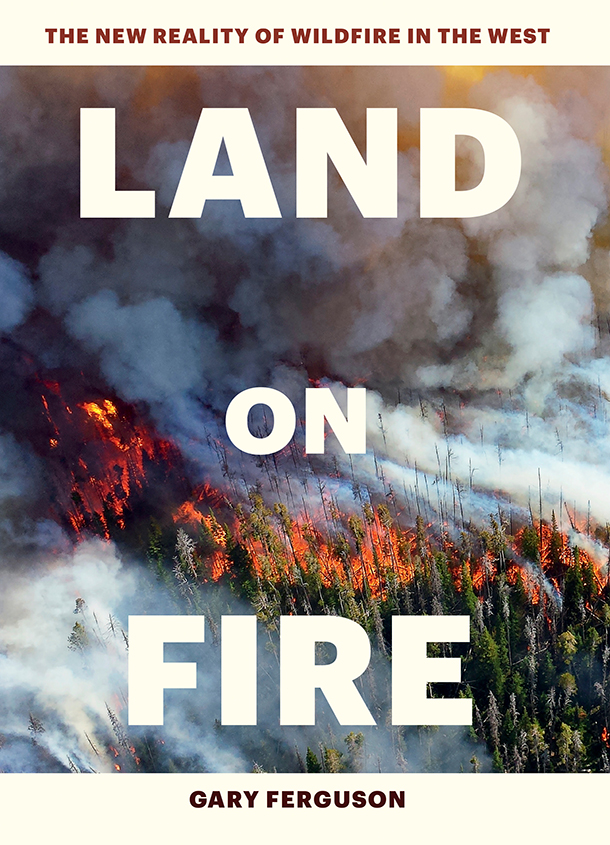

Land On Fire

Air Date: Week of August 4, 2017

July 2017 Whittier Fire in Goleta, California (Photo: Glen Beltz, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

The impact, devastation, and cost of forest fires in America’s West has multiplied in recent decades. Wildfires now blaze fiercer, hotter, and longer than ever before, tearing through communities and overwhelming the forest service budget. Rising temperatures, partly driven by global warming and longer drought seasons have encouraged more insect attacks, and turned western forests into easy kindling for raging megafires - yet people keep building homes in the danger zones. Nature writer Gary Ferguson sits down with host Steve Curwood to discuss his new book, Land on Fire, the new reality of wildfire in the West, and important tips for homeowners to help protect their property and lives.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. From much of the year, wildfires rip across the western United States, stretching through Canada and as far north as the forests of Alaska.

Wildfires once took hold only in hot, dry summer months, this year in the United States alone, more than two million acres of land were burned before the first day of spring. In its scramble to prevent and put out these blazes, the forest service now spends over 50% of its budget on wildfire fighting programs. This new, alarming situation has several causes, and a new book lays them out. It’s called “Land On Fire,” by nature writer Gary Ferguson, and he joins us now.

Gary, welcome to Living on Earth.

FERGUSON: Thank you, Steve. Great to be with you.

CURWOOD: So, why did you write this book?

FERGUSON: Well, Steve, when I was trained as a naturalist, way back when in the 1970s in the Sawtooth Mountains of Idaho, my mentor, who was a brilliant ecologist, happened to get me looking at landscape in terms of fire. Our landscapes throughout the country but especially in the American west have been really shaped by fire for thousands of years. Everything we see -- the shapes of the trees, the way they're clustered, the plants that grow there, the animals that exist -- have been shaped by fire.

What I started seeing though in the last 15 to 20 years especially is a different kind of fire roaring across the west. These are not the natural-stand maintenance fires that burned across thousands of years every 10 or 12 years to clean the forest and stem disease. These are bigger and hotter. They're coming more often, and they're having a pretty big consequence to both the landscape and the communities.

Author Gary Ferguson’s new book Land on Fire addresses the new extremes of wildfire in the western United States. (Photo: courtesy of Besse Lynch)

Let me mention very briefly two things are going on that sort of create a perfect storm right now in the American West. One is unnaturally heavy fuel load on about 300,000,000 acres, in other words, about three times the size of California that came from having about 80 years beginning in the 1915, 1920 era of overly heavy fire suppression, putting every fire that burned out as soon as we could. So, those fuel loads are meeting with climate change, and so when lightening strikes or a campfire is left unattended, we end up with a fire that's spreading very quickly, so this is a really, really different situation.

CURWOOD: In other words, this is not your grandmother's fire anymore, huh?

FERGUSON: You are so right. It is not your grandmother's fire. Yes, that's true. In fact, in the last 15 years, Steve, we've had so-called “mega fires,” which are gigantic fire events of 100,000 acres or more. We've had a dozen of those events in 12 of the last 15 years, so that's a profound difference as far as what was going on in the late 20th century.

CURWOOD: Now, right at the beginning of your book, Gary, you illustrate the sheer size and impact of a wildfire that really gets going and just blazes through one of America's western forests. Please paint a picture for us now of how a forest fire escalated from those few embers to a huge wildfire and then back to ash.

A Camarillo, California wildfire in early July 2017 swept over more than 50 acres of land (Photo: Hanlu Cao, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

FERGUSON: Well, typically there is an ignition source that's not as big as trees, and what I'm talking about are grasses. Many of the fires that are burning right now in California started as grass fires, either as grass understory in the forest or the edge of the forest, and then it moves into the trees. One thing about that, right now we have in large part because of drought conditions, a massive invasion of cheat grass, which is a non-native plant that drives out thoroughly by the middle of June and becomes almost like flash-paper. So, sometimes if you're in a cheat grass field -- and it's worth noting that 100,000,000 acres of the west are now in cheat grass -- that can torch off in very short order, and then it will come into the fuel load, the smaller twigs and branches that have fallen off the trees that, again, normally 200 years ago would've been cleaned out by these periodic, fairly low intensity fires burning through every 10 or 12 years. It gets into that and then from those smaller fuel loads it, especially if there are wind conditions that come up, then it can start actually burning up trees and crowning out as they call it, going all the way up the tree and completely consuming the tree, and from that point, depending on the topography and local wind conditions and so forth and, again, how dry it is.

The loss of humidity, even a couple of percentage points in humidity has a really big effect in making something combustible. There are places in the forest right now that have a percentage of dryness around 10 percent on the dead timber, and that's two percent less than what we would buy at the lumberyard to build our homes with, the two by fours. So, we're or talking about incredibly flammable materials.

CURWOOD: Back in 1910, you wrote about this huge fire that occurred. A lot lessons learned. But these big big fires coming much more often these days. To what extent can we look to climate change -- global warming -- as an impetus for this change in how fires are?

Evidence of the Pine Bark Beetle killing trees in Kings Canyon National Park, California and making them easy tinder for a megafire. (Photo: Laura Camp, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

FERGUSON: It’s really quite profound. For starters, since 1972 our fire season has grown by about 75 days in the west. In fact, some places in the southwest are nearly to the point where they're having fire seasons all year long. One of the reasons that's happening is, with the warmer temperatures and the droughts also associated with human-caused climate change, the snow packs are going off earlier and, of course, as the snow pack go off, not only is there less water available to vegetation, but the ground itself is more exposed to sun and wind and dries out and becomes very, very flammable. The droughts I mentioned, there've been three major drought cycles in the west, significantly caused at least in part, not entirely but in part, by human-caused climate change.

Those droughts are stressing trees to the point where they're really, really susceptible to insect infestations. It's really sobering to consider that last year alone, 2016, California lost 60 million trees to drought or drought-related disease or insect infestation. That's a phenomenal tree kill. It's important to keep in mind that in the American west, things don't biodegrade the same way in the east because we have such a lack of moisture. So, the only way that the biomass, if you will, of trees and plants, returns to the soil is typically through fire. So, by putting those fires out, we really created that fuel load. This is why you're seeing many land managers pushing harder and harder for so called “prescribed burning,” where when it's safe to do so, they will light fires to mimic what nature used to do on her own before we started to interfere with her. Again, the heavy fuel loads that we created unwittingly in the 20th century by putting out every maintenance fire, if you will, created a bad situation, as far as what's there to burn.

CURWOOD: By the way, what is a maintenance fire?

FERGUSON: A maintenance fire, and the actual full term is called by ecologists, “stand maintenance fire.” It really refers to a natural burn that was a part of the western landscape for, for thousands of years that would touch off 8, 10 or 12 years or so, usually by lightning, and it would burn at a fairly low intensity. So, we're talking six to eight foot high flames, 1,200 degree temperatures. Now, if you compare that to a megafire, we might have 150 foot flames, 2,000, 2,200 degree temperatures, but these stand maintenance fires would come through and clean up those smaller trees that had fallen and branches that had fallen, clean up the dry grass, stem the insect invasions, and then they would be gone, and we be left with a healthier forest.

An airplane helps contain an Alaskan forest fire by dropping borate salt fire retardant. (Photo: JLS Photography – Alaska, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Yes, you write about the Pine Bark beetle and other critters that go in and kill trees, and I believe at one point in your book you say that these insect infestations which have been accelerated by drought have become even more important than lightning strikes that typically would set off forest fires.

FERGUSON: Well, it's interesting. The Pine Bark beetle, especially, it's been with the western forest for a very very long time, but it used to be that winter temperatures were cold enough to limit the spread of the Pine Bark beetle to kill off the populations. Now that's not the case anymore. In fact, not only are they not being killed off, but they've managed to double their reproduction rate in a given summer. So, this creates a lot more insects.

Meanwhile, if you're an insect attacking, say, a Lodgepole pine during a drought, the Lodgepole pine would normally have defenses to release a lot of pitch and literally what they call "pitch out" the insects from the invasion. But, with drought, that moisture is no longer available, so it's much easier for those insects to make their way into the trees. And then, as a lightning strike hits or a campfire or a chainsaw spark or something like that, again we got these big fuel loads met up with tremendous climate change consequences, and even winds have picked up in some places and, of course, winds can be really dangerous ingredient for a wildfire, especially a megafire that's over 100,000 acres. Very dangerous to housing subdivisions and, of course, very, very dangerous to the men and women who are fighting fires.

CURWOOD: So, let me add these factors up that you present in your book, Gary. So, there is more fuel because of fire suppression that is available in many of these forests, A. B, with things getting warmer and the climate, the bugs that attack trees aren't getting killed as much in the wintertime, so they can kill trees and, of course, a dead or nearly dead dry tree is much more susceptible to fire, and then you say that the trees themselves because of the drought their typical defenses aren't working all that great, and overall it's a bit warmer. Sounds like the perfect storm or should I say, the perfect firestorm?

FERGUSON: Yes, it really is, Steve, a perfect firestorm. That's a great term for it, and one other thing to add in the mix as if we didn't already have enough, and that's the fact that in areas in United States that are often referred to as wildland urban interface, and what this means -- It's a complicated title that just means housing developments and businesses that come up against large slices of natural vegetation -- and It's really quite amazing. 60 percent of the homes that have been built in the United States since 2006 have been in this wildland urban interface and some 200,000,000 acres right now are considered at high fire risk. That's where the development is going and unfortunately too often we're doing developments in a way that just are not so called “fire-wise.”

CURWOOD: Hey, Gary, how many people here in United States live in what you call this wildland urban interface in the west there?

FERGUSON: Well, amazingly, it's just about a third of the population of the country, over 100-million people living in a wildland urban interface. Again a significant portion of that interface is already mapped as high fire danger, about 70,000 communities, we could think of in those terms as well. And of the 70,000, it's worth mentioning that only three percent so far have done steps -- and they are relatively simple steps -- and they're very effective. They're not fireproof but to leave their communities more fire resistant.

CURWOOD: So, talk me through what people living in this high-risk area of wildfire there in the west, this wildland urban interface. What are the steps that individuals should take, and then what are things that communities should do in light of the reality of the changing fire regime?

Two members of the Idaho City Hotshots work on the Springs Fire on the Boise National Forest in August 2012. (Photo: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

FERGUSON: Well, there are some wonderful efforts going on right now in Colorado, groups coming together in neighborhoods forming what are called s”aws and slaws,” and so they basically have a local firefighter or forest service official come and help them with thinning the forest around the subdivision so that they can have less of a chance of a fire raging into their housing development, and the slaws part is after they're done cutting the trees they have a picnic with beer and coleslaw and whatever, and it has been a way to bring communities together.

As far as individual homes, very simple things: Taking a five-foot perimeter around your house and covering it with nonflammable material. Putting screen mesh over attic vents; going around and giving the firefighters basically a 40 to 50 foot defensible perimeter, it's called, by cutting errant bushes and smaller trees away and just by doing that, this may seem like it wouldn't make a lot of difference, but to give you an example, in the Black Forest Fire a few years ago in Colorado Springs, one subdivision that had done those things experienced a home loss of four homes out of 69. Right next door, there was another subdivision that hadn't done anything. They lost 61 homes out of 67. So, it really, really can make a difference, a very big difference.

CURWOOD: So, this business of fighting fires, protecting lives and homes and such, is expensive. How expensive is it, and how is the federal government which I gather does most of the fire fighting in the west, how is the federal government doing in terms of managing the economic impact of all this?

The aftermath of the 2010 Schultz Fire in the Coconino National Park, Arizona, which burned more than 15,000 acres of forest. (Photo: Coconino National Forest, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

FERGUSON: Well, it's, it's been devastating, especially to the Forest Service. Forest Service can, in some years, spend between 70 and 90 percent of their budget on fighting fires. That means nothing else for fire prevention or, you know, fire-thinning and other forest treatments. It's a price tag on about $3 billion dollars a year in hearty fire season, and that's what we're getting more of than not these days. What we have right now is the Forest Service and the taxpayers, of course, who fund them, spending all of that money to fight fires in developments that shouldn't have been developed the way they were. And so at some point, besides offering county commissioners incentives for doing it right, there are some people talking about, we need to also perhaps give them some of the burden of the cost of suppressing fires, especially in developments that were simply not designed properly, knowing what we know now.

CURWOOD: And Gary, at one point in your book you write that this situation may turn around, but unlikely in our lifetimes, that we are entering a new normal. We're already in it. It's probably going to get worse before it gets better. So, what can you say to encourage folks about this problem? Where is the bright side of this?

FERGUSON: Well, one thing I would love to see happen that's very practical, there's a bill in the house of representatives, House Bill 167 that has been sitting there for two-and-a-half years that would give the Forest Service access to emergency funds in high fire years, much like FEMA steps in after a hurricane or a tornado or a flood. Right now the Forest Service only has its own budget to spend, and sometimes it's inadequate, and it again cuts them off from that process of educating and going out and helping people thin the woods, do prescribed burns to make these forests less flammable, less likely to burst into a megafire in the years to come. We also, quite frankly, really need to take climate change very seriously and start embracing alternative technologies, look at our carbon footprint, endorse regenerative agriculture that holds crops in the grounds that become carbon sequestration.

These are all very important things. We got the smarts. We've got all we need to know to actually do these things. We just simply have to have a heart and the will at this point, and, I think, as fires continue to rage in and a bigger and bolder fashion, they will continue to knock on our door trying to get our attention to take all of this very seriously.

CURWOOD: Gary Ferguson is a best-selling nature writer and author of the new book, "Land on Fire: The Reality of Wildfire in the West.” Gary, thanks so much for taking the time with me today.

FERGUSON: It's been a pleasure. Thank you, Steve.

Links

More about Gary Ferguson on his website, Wildwords

Land on Fire: The New Reality of Wildfire in the West

Interactive map of current wildfires burning in the United States

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth