Big Chicken

Air Date: Week of September 22, 2017

Chickens in an industrial poultry farming facility. (Photo: Chesapeake Bay Program, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

Before science knew much about drug resistant microbes, farmers routinely used antibiotics to plump up livestock such as chickens for market. Author Maryn McKenna traces how this history of antibiotic use shaped agriculture into today’s mostly industrialized market. Maryn McKenna joined host Steve Curwood to discuss the issues, and changes underway in poultry factory farming today.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Back in 1970, the average American ate less than a pound of chicken each week. Today it’s more than twice that. And in the rush to bring all that poultry to market some industrial scale producers relied on antibiotics to keep infections down in their massive factory farms. But as the wisdom of that has been questioned, a lot of chicken producers are scaling back on their wholesale use of antibiotics.

For an update on this trend we turn now to Maryn McKenna, who has written a new book called Big Chicken. Maryn McKenna is a journalist and author who focuses on public health and food policy, and she joins us now from Atlanta, Georgia. Welcome to Living on Earth.

MCKENNA: Thank you.

CURWOOD: Now, we've known about the risks of antibiotics in agriculture and livestock for a long time. What prompted you to begin writing this particular book? I know you've been active in this area for much of your career as well.

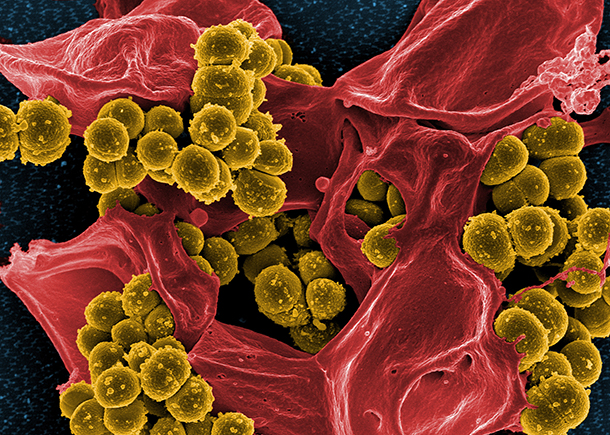

MCKENNA: So, the reason why I wanted to look at this was really twofold. The first was, seven years ago I wrote a book about antibiotic resistance generally. It's called "Superbug", and it was my attempt to tell the story of the emergence of antibiotic resistance by sort of telling the biography of a single organism, MRSA, or drug resistant staph. And I went into that project thinking that I knew what the story was, that there were two epidemics of staph, in hospitals and in the wider world, what's called Community Associated MRSA. That's the staph that affects kids in school and has ruined the careers of a lot of pro athletes, and it turned out that that was wrong. There were actually three epidemics of drug resistant staph around the world, in hospitals, in the community, and also in farms, and the statistics that I stumbled across in researching that were that we use in the United States four times as many antibiotics in animals as we are in humans, and that just made no sense to me because I just emerged from talking to people who are saying, “We have to be conservative with antibiotics. We hasve to be very careful how we use them.” And yet here on the agricultural side people were tossing antibiotics by the literal ton into animal feed.

Scanning electron micrograph of methicillin-resistant Staphylococccus aureus (MRSA) and a dead human neutrophil. (Photo: NIAID, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So in your work on MRSA you found that not just the hospital, not just the locker room, but, whoa, on farms and among farm workers. But how is the antibiotic drug resistance in the poultry industry different or unique compared to what happens for human antibiotic use?

MCKENNA: Well, in some ways it's not unique at all. The problem with farm antibiotic use is that we use the exact same antibiotics in farm animals that we do to treat human infections. What the implications of that are that if a resistant bacteria arises in animals as a result of that antibiotic use and then travels off the farm to affect humans in some way, then the drugs that we would have relied on no longer work because they've been undermined by that use on the farm, and the big fight over farm antibiotic use, pretty much from its inception, has been whether those bacteria actually do travel off the farm. They're not just resident with the animals, but they affect human health far from the farm, and I think it's very well established now that that is the case, that it does have a broad effect, but it was tracing that chain of evidence that was one of the things that made me want to do this project and write this book.

CURWOOD: And talk to us about why farmers started using antibiotics back after they were discovered and particularly the economic conditions that made it advantageous for that.

MCKENNA: So, like a lot of things. This is kind of a story of good intentions gone awry. So, immediately after World War II, several things are happening. First, it's the start of the antibiotic era. Penicillin's out in 1944, 1945, and there's great rejoicing at how powerful these drugs are to reverse infectious diseases. At the same time the food production system has been really undermined by the war, and there's a great deal of excess capacity because all those troops were being fed and now all those troops have gone home. So, out of that desire to protect the food production system while also cutting costs, comes this idea of using antibiotics as what are called "growth promoters", which are tiny doses that you give animals routinely that somewhat mysteriously at the time cause them to put on weight much faster than they would have otherwise. Now, we would recognize that today as being a disruption of the gut microbiome that affects nutrient uptake, but in the 1940s and 1950s, they didn't really know what was going on. They just knew that it worked.

CURWOOD: And in fact today as you point out it doesn't make these chickens any fatter, to use this.

MCKENNA: It's true, and it's not just chickens. You know, this goes on in pigs and this goes on in cattle as well, and all the major meat eating animals. It is absolutely true that in the United States and in Western Europe growth promoters don't work anywhere near as well as they once did. That's probably one of the reasons why industry was willing to give them up in response to this Obama administration pressure, but they're still very much used in the developing world, and that is going to be where the fight over this turns now because in conditions of more crowding, of less hygiene, of less precision nutrition, all of which we take for granted in agriculture in the United States, but we can't take for granted in the developing world. Growth promoters and preventive uses of antibiotics in animals are still really valuable, but they still have the same resistance promoting effect.

Antibiotics helped chicken to become the most consumed type of meat in the U.S. (Photo: Peter Cooper, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: There is a basic thing about antibiotics and livestock, and that is producers are tempted to use them more and more in crowded and not healthy conditions. To what extent do these antibiotics allow for these huge factory farms that you talk about to exist, A, in the United States but, B, overseas?

MCKENNA: So, using antibiotics routinely in farm animals does two things. The first is this growth-promoting effect where you give them very small doses, literal grams per ton of feed, and it causes them to put on tasty muscle faster, and to me that's the thing that really starts the whole ball rolling for what we now think of as industrial scale agriculture because once you can produce animals a little more quickly or a little more cheaply, it becomes tempting, I think, to do that more and more. And so, we start to move toward the farms that are running in a more mechanized fashion. Then, as they get bigger, someone has the idea to use just a little more antibiotic. Still, doses far below what it would take to cure an infection, but enough that it protects the animals from being in such close quarters with each other, and so we get a very efficient system for growing very inexpensive protein, but with the downside of resistant bacteria being created in a way that no one really intended, but for a long time no one really took account of, either.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about food poisoning and its connection to the widespread use of antibiotics in livestock. In your book, you mention a case actually involving egg processing that there was a substantial Salmonella outbreak, and we know even today organizations like the Consumer's Union will publish studies saying that a fairly large percentage of poultry has a lot of unhappy bacteria on it, whether it's Salmonella or Listeria. How is that related to this overuse, in your view, of antibiotics?

MCKENNA: So, back before the growing of meat animals became industrialized, when farms were still pretty small, if there was an outbreak of food borne illness, it was usually a pretty local one, and you had a fairly good sense of where it was coming from, whether it was from a particular farmer or a particular dinner or a particular place where a small group of people had eaten. As farms get larger and larger, and the industry collapses into larger companies that are sending the foods that they produce across greater distances, first, food borne illness outbreaks get larger, and they also get much more spread out so they're harder to solve.

McKenna’s new book follows the history of antibiotics in modern agriculture. (Photo: courtesy of Holly Watson PR)

Then, add antibiotics on top of that. So, the bacteria that cause foodborne illness are bacteria that come from the animals' guts, and, when you are feeding antibiotics to those animals, the antibiotics are going into their guts as well and influencing the bacteria in their guts to turn toward antibiotic resistance. Those bacteria may get on the meat that those animals are becoming and travel with them into the food system, into home kitchens, into restaurant kitchens, into supermarkets. So, you get for the first time, both antibiotic-resistant food-borne illness and also outbreaks of food-borne illness that are much harder to track back to the places that they come from than they would formerly have been. So, while it's the concentration of agriculture that starts the ball rolling for larger more diffuse outbreaks of food-borne illness, adding antibiotics to the mix makes them much more dangerous.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about the animal welfare part of the overuse of antibiotics.

MCKENNA: So, the thing about using antibiotics routinely, and I want to be clear here that the antibiotic use that deserves scrutiny is not antibiotic use that cures infections in animals that are sick. What we're talking about here is antibiotic use in animals that are not sick for purposes other than curing infections. If we did that in humans, medicine would immediately consider that to be inappropriate. We only use antibiotics to cure infections in humans. We overwhelmingly don't do that in agriculture. So, once you start protecting animals from the consequences of the way that you're keeping them, whether that's feeding them lower quality protein or cramming them together in a barn or feedlot in a density that they wouldn't naturally be able to tolerate, then their quality of life naturally goes down.

CURWOOD: Now, Maryn, you wrote that attempts to regulate antibiotic uses on farms started in the 70s but usually failed. What happened? What were the conditions that prevented policymakers from curbing antibiotic use in agriculture back then?

MCKENNA: So, the story of how we almost got in the United States to regulating this practice is really a sad story. So, to set the stage a little bit, this widespread use of antibiotics on farms is happening by the mid-1950s. The first troublesome outbreaks of antibiotic resistant food-borne illness are happening by the mid-1960s, and by the end of the 1960s, the first government to take a look at this is actually the British government, which by 1971, restricts all growth promoters. And that turns attention back to the United States since we are the home of this antibiotic use and a much, much larger agricultural economy.

So, the Carter administration comes in 1976, and they decide that one of the things that they're going to do is they're going to reverse this FDA policy, these licenses granted in the 1950s. So, there's a very activist new FDA commissioner. His name is Donald Kennedy, and he sends a message to the manufacturers of veterinary antibiotics which are most of the large pharma companies in the country. He puts a notice in the Federal Register saying he's going to summon all of them to a hearing. And at that hearing he's going to ask them all to prove that their products as used in agriculture are safe. And if they can't prove that, then he's going to yank the licenses, and he never gets to hold that hearing because a very powerful Congressman from the south who has oversight over the FDA's budget sends a message up to the Carter White House that, if this hearing goes ahead, then this Congressman will hold the FDA's entire budget hostage, and thus the opportunity goes away. That Commissioner Donald Kennedy is on loan from Stanford University, and within a couple of years he has to go back, and the Congressman Jamie Whitten puts a rider on the appropriation bills for basically the rest of his tenure in the House of Representatives saying that antibiotic use in agriculture cannot be re-regulated by the FDA, and he keeps that rider going until he retires in the 1990s.

CURWOOD: So, talk to me about how the political landscape has changed. Particularly, you say the year 2013 is a pivotal year in this story. What makes that year so significant?

MCKENNA: So, this stalemate that the government and agriculture and the veterinary pharma industry are in goes on for decades, and then a whole bunch of pieces of the landscape change. That stubborn Congressman retires, and the Obama administration comes in in 2009 and somewhat mysteriously decides that they are going to make this one of their issues, and one of the things they do is they say to the FDA, “Let's revisit what was supposed to happen in 1977, but was prevented.” So, at the end of 2013, the FDA moves to do a thing that in 1977 they didn't think about. They propose not a law and not a regulation - because both of those could be interfered with by Congress - but instead a semi-voluntary measure that they call a “guidance,” which is something that the FDA can do without any of the other branches of government touching it.

Maryn McKenna is a journalist and author who has reported on antibiotic drug resistance through much of her career. (Photo: courtesy of Maryn McKenna)

So, they put forth a set of guidances that recommend that drug manufacturers change the labels on their drugs so they can no longer be used as growth promoters on farms, and somewhat to everyone's surprise all of the pharma industry falls in line. The FDA gives the industry three years to try this, from the end of 2013 to the end of 2016. All of the pharma manufacturers agree, and so, as of January 1st of this year, to use antibiotics as growth promoters is effectively illegal in the United States, putting us in line with what Europe did more than 10 years ago.

CURWOOD: Maryn, from your perspective, what are the alternative models to raise chickens in more environmentally and economically and sustainable ways, and some would say even more humane ways?

MCKENNA: So, the thing that I think is really interesting about this is that giving up antibiotics has created a kind of ripple effect through the industry in a few different ways. First, it opens up the market, I think, to the small and medium sized producers who want to raise birds in an extremely high welfare, out on pasture, very old-fashioned looking manner. Those birds are allowed to live a lot longer, they exercise, they have what look like happy lives. They also taste different, and they are a challenge for consumers to embrace, but forgoing antibiotics has also caused the major producers to really start making other changes in their production as well.

The best example of this is Purdue Foods, Purdue Farms, and they have said to me reconsidering antibiotics caused us to rethink an awful lot of other things about the way we raise our chicken, and now they're doing things like cutting windows in the walls of their barns and putting herbs and probiotics and prebiotics into their chickens’ diets and allowing the chickens to exercise. So, rethinking antibiotics, I think, is changing the entire way this protein, chickens, are produced. And the question will be, then, can chicken teach the rest of the meat economy that this is the way that's worth going?

CURWOOD: Maryn McKenna is a journalist and author. Her new book is called "Big Chicken: The Incredible Story of How Antibiotics Created Modern Agriculture and Changed the Way the World Eats". Thanks so much, Maryn, for taking the time.

MCKENNA: Thank you for having me.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth