American Seafood: Heritage, Culture & Cookery from Sea to Shining Sea

Air Date: Week of November 24, 2017

Fresh Spanish mackerel on ice, just before being taken to Barton Seaver’s kitchen to be gutted and cooked. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

Barton Seaver is a chef with a mission: to rekindle America’s taste for abundant seafood. His new book catalogues more than 500 species of seafood interspersed with recipes, photographs, and an extensive history of America’s relationship with food from the sea. Host Steve Curwood joins Seaver at a dockside fish market in Portland, Maine to scope out the freshest, most sustainable fish and shellfish – and then, they shuck oysters and cook up some tasty, fishery-friendly mackerel in his kitchen.

Transcript

[STREET SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: Late one morning on a brisk fall day we’ve come to Portland, Maine, to talk with celebrity chef and author Barton Seaver. His new 500-page book is called "American Seafood: Heritage, Culture and Cookery From Sea to Shining Sea". And he asked us to meet him at a popular fish market that backs onto a dock loaded with lobster traps and buckets of bait fish.

[SOUNDS OF FISH MARKET, WATER, DUMPING CRATES, ETC.]

CURWOOD: Inside the market it seems there's fish and ice everywhere.

The storefront of Harbor Fish Market in Portland, Maine. (Photo: Corey Templeton, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

SEAVER: So, we can start over here on this wall and see 20 kinds of oysters - John's River, Nonesuch, Wawenauks. So, you've got Damariscottas. You've got Dodge Cove, Glidden, Wiley. I mean, these are some of the truly charismatic places of the Maine coast, each of these representing a “miroir”, if you will, each oyster a taste of the people, the place, the tides, the currents, the history. You can see the different environments are reflected quite literally in the shape of the oyster shells and the color of them. You see here, these Nonesuch have a green hue to them. That's a marine algae that grows on the outside.

CURWOOD: I enjoy oysters, but I've never actually tried to shuck one at home. If I bought these, what would I have to do to open it once I got them home?

SEAVER: There is the fact that most Americans are put off by that this is food that inconveniently comes wrapped inside of a rock. [LAUGHS] But oysters were once of the most popular food in America. I mean, there were the food of both the rich and the poor. Penny oyster bars lined the Lower East Side, you know, carts, saloons, and speakeasies that celebrated this culture.

Oysters reflect their local “merroir”, taking on a particular flavor based on the environment in which they grew. Their looks are also borne of their origins: above, Nonesuch oysters – so named for the Maine river estuary where they’re cultivated – are naturally green with harmless algae and stand out among twenty or so varieties. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

So, something interesting I'd like to point out to you as we walk over to the fillet fish case, here. They’ve got 25 different kinds of fish. Half of them are orange, meaning half of them are salmon type - Arctic char. You've got farmed salmon coming from four different countries. We've got two different kinds of wild salmon coming from Alaska. We've got trout in the back there which is a salmon relative. So, our species preference in America is really very limited. Americans love shrimp, tuna, and salmon. Over 65 percent of our total consumption of seafood in this country is just those three varieties. But what's great about this market is that, yeah, you've got farmed salmon from Chile, from the Faroe Islands. You've got King salmon and Coho coming from Alaska. Next to it you've got halibut and haddock. You've got bluefish. You've got cod...Cusk, a member of the cod family.

So, interwoven between these international commodities seafood trade is the heritage, is the fish, the very backbone upon which New England and her communities were founded. Cod is to New England as cotton was to the south. You know, it was the commodity upon which the wealth of this nation first began to accumulate. It was how we began to take our first steps towards independence by becoming a mercantile nation.

Typically, at least half of the fillet varieties offered in a seafood market are what Barton Seaver calls “orange fish” – in other words, those in the salmonid family: salmon, trout, and char. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

We continue over and right in front of us is a representation of our bioregion in the form of whole fish. Most chefs have never seen or worked with whole fish, let alone consumers.

CURWOOD: So, I want a little advice about fish buying. I'm not an expert at all on this, but I'm looking at this mackerel, and it looks really great. For some reason, it's shiny, and what should the buyer of seafood especially whole seafood be looking for aside from using one's nose of course?

SEAVER: If you look at the eyes, basically what you're looking for in summary is vibrancy. You want it to look as close to living as possible. Here with a mackerel you still see this little murderous underslung jaw as though it's still trying to intimidate you. You see this flesh, you see that it bounces back with gentle pressure, meaning that it's still firm and you see that in this really gentle light that we're under here, you see that it's reflective. This thing is close to alive. It is a shiny, beautiful, gorgeous specimen, and, if you can't say that about the fish, I don't think it's worth buying.

CURWOOD: Barton, at one point in life I heard someone say, “The best fish to buy the market is the cheapest.” Why? Because it's the freshest. They have...Tthe most anxious to get rid of. What do you think of that old saw?

SEAVER: Cheapest might not be the best way to go, but certainly the question there is what's the catch of the day? Well, hey, today, ocean perch. It is abundant right now. The fisheries are just killin' it, bringing it in day after day. This fish was just landed yesterday on the exchange in Portland [Maine] just yesterday morning. Beautiful fish. Just out of rigor. Today we've got it for $3.99 a pound. Wow! What a great deal.

Harbor Fish Market is located on Portland, Maine’s working waterfront. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

CURWOOD: And it seems to be about the cheapest fish there.

SEAVER: There's that benefit too. But what we do when we walk into a grocery store, really into any retail scenario, and we say, “My recipe says red snapper,” we are making demands not only of this business, we are making demands of fisherman beyond that service business, and ultimately of the ecosystem. And, when we act with such hubris to think that it's our place to tell ecosystems and fishermen only what we're willing to eat rather than ask of them what they are able to supply, we are creating inherently unsustainable systems.

CURWOOD: Well, we've been trained with factory farming. I mean, I don't know as consumers that we're really trained to think about buying what's available and what's smart as opposed to what the recipe book says.

SEAVER: We're beginning to get there, and, to be quite honest, I mean one of the great victories in, of humankind is the fact that we're able to produce so much food, and there's a lot of controversy about how we do it. But the fact that we are able to feed so many, easily a victory.

CURWOOD: Frankly, I do enjoy eating, I got to admit it.

Fishermen with cod and halibut, Alaska, 1927. (Photo: Courtesy of Library of Congress)

SEAVER: Hey I do too. Oh yeah, but you know I think people are beginning to sense that through food we connect to civic-social virtues, values in ways that are very exciting that make food an exploratory opportunity not just a satiation exercise.

CURWOOD: Barton, I grew up in Boston, and close family friends, the dad worked as a longshoreman and would bring mackerel home to cook and fry. I don't think since I was a teenager I've seen a whole mackerel.

SEAVER: Well, why don't we pick some of those up and take him back to my kitchen and we'll help re-live some of those memories for you.

CURWOOD: Alright!

[MUSIC: Crooked Still, “Come On In My Kitchen” on Shaken By a Low Sound, composed by Robert Johnson, Signature Sounds]

CURWOOD: Coming up, Chef Barton Seaver takes us home to share his secrets for savory seafood. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies - combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning in to the Race to 9 Billion podcast, hosted by UTC’s Chief Sustainability Officer. Listen at raceto9billion.com. That’s raceto9billion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

Three specimens of the “true mackerel” variety. Mackerel is a common name that refers to a variety of species of pelagic fish. (Photo: Michael Piazza)

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Crooked Still, “Come On In My Kitchen” on Shaken By a Low Sound, composed by Robert Johnson, Signature Sounds]

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

[MUSIC ON THE VICTROLA: King Oliver and his Creole Jazz band/Louis Armstrong, “Alligator Hop,” on King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band: Alligator Hop, composed by King Oliver, Gennett Records]

CURWOOD: We’ve come to the 200-year old home of celebrity chef Barton Seaver. It’s just up the hill from a Maine coast harbor, and just inside the door there is an old-time Victrola that Barton has cranked up to give us a bit of King Oliver and his Creole jazz band.

[MUSIC]

And, while his kitchen fits nicely into the antique décor, it is strictly modern for Barton when it comes to the cooking.

[SOUNDS OF UNWRAPPING OYSTERS]

SEAVER: So, you were asking earlier about how, how to open an oyster. Well, that's how it is one of the only foods we eat that comes inside of a rock, and the way to open it is to take the rock in one hand, take a sharp object - basically the shank - in another hand point the shank directly at your other hand and then pry with strength. There's a reason why people are pretty intimidated by this.

[LAUGHS]

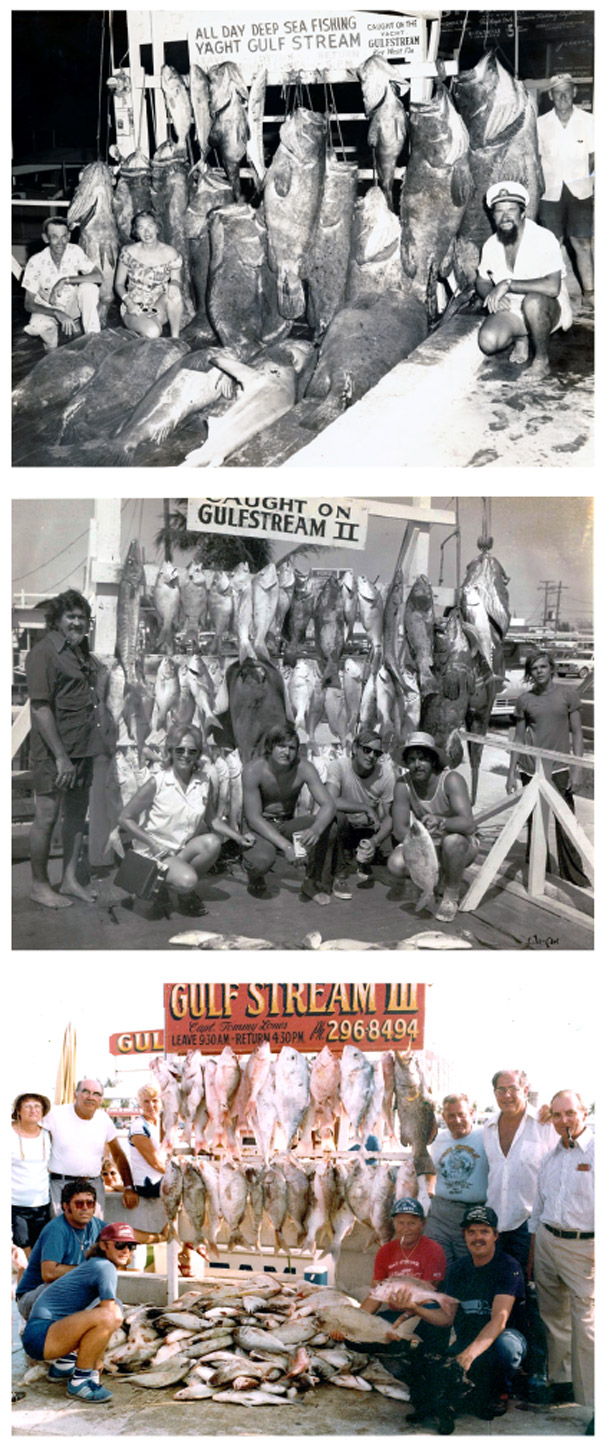

Catch sizes have shrunk dramatically over the years. (Photo: Courtesy of Monroe County Public Library)

So, we've picked up the two different providences of oysters here. So, this is the Nonesuch oysters of my friend Abigail Carrol. She grows these smaller oysters, beautiful shell hinge on them, and these are wild oysters from Damariscotta, powerful tidal river up the coast. You can see, they're just a little bit more unruly in their shape and form and size, and, well, they are a little bit dirtier. It doesn't make them any less, any less delicious, in fact, they both will give off their own charm and unique qualities, and that's the whole point of an oyster.

CURWOOD: What's the secret here, Barton? You got right into that oyster, no problem.

SEAVER: Well, the two shells are held together by the adductor muscle right, in the center. When you look at an oyster, you think it's the round little disc in the middle. That's actually the same muscle that you...That's what we would call a scallop in the scallop animal. In that animal, though, we only eat that muscle. That muscle holds the two shells together. The top shell is flat. The bottom shell, cupped, holds the body of the oyster. You go in through the very back, where the shells meet in the hinge, and once you get the knife between the shells, use a twisting leverage to separate them just enough so that you can get the flat angle of the knife to then slide along the underside of the top shelf and thus slice the adductor muscle free. At that point the oyster is connected to the bottom shell by that same muscle, you scoop out from below, and you have an oyster sitting there jiggling with all of that fresh, beautiful brine and liquor.

Chef and author Barton Seaver at work on a lobsterboat. (Photo: Michael Piazza)

CURWOOD: My mouth is watering already. Thank you. Mmmmmm. Wow. Just fresh....little touch of seawater...really bright.

SEAVER: So, that was the wild Damariscotta. This is the Nonesuch oyster, same species of oyster.

[CURWOOD SLURPING]

CURWOOD: Even more intense flavor to this one with a sort of sweet finish to it. So, you're from the Tidewater area? Chesapeake?

SEAVER: Born and raised, son of the Chesapeake, really the son of downtown DC during a relatively tough time in its history, during the mid-late '80s when crack had just really hit as an epidemic. So, as a means to escape some of that during the summer we spent a lot of our time down on the Chesapeake Bay, a tributary called Patuxent River.

[SOUNDS OF SHUCKING OYSTERS]

There I learned my appreciation for seafood and also learned my understanding of the bounty of waters and created in my mind what, what you call my baseline, what I understand “bounty” in this world to be. And it's a real interesting thing in conservation is that we create an idea of what we think is normal based on our experiences, and then we fight. We fight with all that we are to sustain that, to get back to that normal, but in many cases that normal is so far from pristine or pure or truly sustainable that, when we talk about ecological baselines or even social baselines, we get to the question about sustainability is that, what is it that we are trying to sustain at the end of the day?

Crimping the skin of fish like this Spanish mackerel prevents the fillet from curling in the hot pan. (Photo: Barton Seaver)

From a biological standpoint, we often have no true understanding of what level of biomass or of diversity that we're trying to restore, really, but, when it comes to a social baseline, that's where sustainability becomes understandable. It becomes actionable, measurable, and valuable because what I'm trying to sustain is 5,600 individual licensed owner-operator lobsterman and women along this coast. I'm trying to sustain my neighbors. I'm trying to sustain the fisheries that have forever, since white man populated this area, sustained these communities.

And when I say sustained, we're talking about fisheries here. A lot of people don't understand what a fishery is though, and I want you and your listeners to practice this exercise. Close your eyes and picture a farm. Rows of corn, autumn, splendor, setting sunlight, red barn, gently reflecting back, a one and a half lanE dirt road trailing off into the distance, iconic America, amber waves of grain, the fruited plain. That was easy. I mean, it is rooted within us. Now close your eyes and picture a fishery.

After filleting the Spanish mackerel, Seaver makes a simple cut on either side of the spine to free it and all the bones of the fish in one simple step. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

CURWOOD: It's dockside. For me, it's dockside. It's Boston. It's an area that fishing boats, I don't know if they land so much there anymore, but they used to land there when I was little. It's noisy, and there's lots of wooden boxes and men running around hand trucks and hollering and ice and water splashing everywhere.

SEAVER: Well, this is what people don't often understand. What you just described is, is an industry. It is people, it is action, it is movement, it is an economy. Too often we stand on that dock and we gaze wistfully out of the wine-dark sea and think that a fishery is something that happens over the horizon of our attentions. But you're right. A fishery...You stand on that dock and you hear the sound of those jobs in motion. You turn around you look at the houses and schools and the roads and the quality of life for those people living in that community. And a fishery to me is the ability for a son or a daughter to follow in five generations boot steps onto the helm of that boat to take care of the heritage and legacy of their family. And when we talk about sustainability, if we talk in those terms of saving things that we as humans value, then the ecosystems become the tool by which we remain resilient, and that way I think we turn sustainability around to really be human interest rather than a separate, ecological interest, and then think this is where we make it actionable. We take an oyster in our hands, we slurp it down with a local beer, and we say, "Wait a minute. That's environmentalism? On the half-shell with a six pack? I'm in, buddy!"

Large scallops fished with a dredge, c. 1960. (Photo: Courtesy of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration)

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Unfortunately, as I think about it, that place that I that I recall as a kid, I think it is a hotel now.

SEAVER: That's part of the hard truth of fisheries is that they happen on very valuable property.

[RUSTLING SOUNDS OF UNWRAPPING FISH]

SEAVER: So, every good fish butcher is going to have their own chosen knife. I've got mine that's been with me for 15 years, almost 20 at this point actually. So, Spanish mackerel, just a very shallow slice right behind the nape, right behind the gilt plate. Draw the knife straight through, one simple straight easy cut. Flip the fillet over, note gaping beautiful just milky light flesh. They didn't eviscerate the fish. It's just so fresh, and the texture is so clean. And that's it, filleting a fish. I love coming home with a whole fish because I like to make stock with the head and the bones here, but more likely that will end up in the compost, fertilizing next year's tomato crops.

One of the things I love about mackerel is the bone structure is so simple. One might call it satisfying, so that a simple slice on either side of the bones that run directly down the middle of the fish. I don't puncture the skin or go through. Then a simple flip of the knife underneath, and I can just peel back, in one strip, all of the bones encased in a very thin sort of sheath of flesh that keeps the entire fillet intact. Beautiful, boneless, cooks evenly, that golden mottled skin with reflective, silvery, cutaneous fat. Beautiful fish. Beautiful fish.

Flames leap up from the pan as Seaver finishes the pan-seared Spanish mackerel in a rum flambé. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

I like to heavily season mackerel. The flesh is so fatty at this time of year as they’ve been stalking with those little murderous underslung jaws, alewives and capelin and all sorts of fish up and down the coast as they've been marauding schools of baitfish, and they're so fatty that the salt is needed to kind of tense up the flesh and to bring it together says it has a nice density when it cooks out. So, like with all fish I tend to leave it to salt for about 20 minutes, so the salt penetrates evenly, doesn't just sit on top but actually becomes part of the structure, and part of the texture and really has its chemical effect all the way throughout, adding to that density. Next ingredient, well, this is fresh garlic strewn out of, straight of our garden. It’s a type of garlic called Music. All right, now we just enjoy some of this beer until that salt kind of kicks in, and we'll start sauteeing up.

[LIGHTING THE STOVE]

SEAVER: So, we're doing a very simple straightforward dish. It might sound a little complicated, but it's kind of four ingredients. You got your fish. We're going to saute it in butter, herbs and lemon. Well then, I'm going to add a fifth ingredient just for you, Steve. We're going to, we're going to blow this up.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Blow this up, Barton?

SEAVER: Yeah. Well, this is New England, so I'll throw some rum on there just to vary it and do a little flambe, just to get your spirits rolling. So the butter is going in.

[SIZZLING]

SEAVER: Then the lemon, herbs, and garlic. And then, into each goes the fillet. I use the herbs to baste the fillet with some of that brown, garlic-infused butter, rub that onto the fish a little bit. You see the lemons beginning to carmelize and beautiful. The rims are burned, just beginning to smell. It smells incredible.

And now, you take that fish. You can see it. It didn't even have an idea of sticking to the pan. One of the keys there is using high heat, and that fish is going to be cooked through here in just under five minutes or so.

And then, Steve, once for New England. I'll turn the burner back on here for myself a little myself a little room. Now, we're going to flambe this. So I'm going to give this a shot of rum. This is good old Havana.

The finished Spanish mackerel, pan-seared with butter, herbs and rum. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

[SIZZLING]

A little bit of butter on top. Let it melt in, create that sauce. Take that carmelized lemon, drizzle it over to finish it out. And there we go. Pan-seared mackerel with herbs and a shot of rum.

CURWOOD: Wow, you make it look so easy, but it's not.

SEAVER: You know, truth be told, let's take some things out of this recipe. Let's take out the booze. Let's even take out the garlic and, heck, you can take out the herbs or the lemon, and what you've got here is a cast iron pan. You've got a beautiful piece of fresh fish, the catch of the day down there, the best looking fish they had at the market. Bring it back here. What is it? It's fatty, late autumn, beautiful mackerel. So rich, that fat renders off on your fingers just by the touch, salt it, and just let the salt sit until it absorbs deeply into the flesh. Saute it in hot pan in nothing but butter. Let that skin crisp up just three minutes until it begins to just show a little bit of doneness along the sides. Turn it over and turn the heat off. Wait another three minutes. It's cooked all the way, through, gentle, slow, and you have a beautiful piece of fish that tastes like everything beautiful the ocean has to offer. Bottom line is, cooking good fish is as simple as this. Buy good fish.

[SOUNDS OF CUTLERY]

SEAVER: All right!

CURWOOD: So what's the word? “Bon?” The second word is “appetit?”

Barton Seaver and host Steve Curwood with Seaver’s new book, American Seafood: Heritage, Culture & Cookery from Sea to Shining Sea. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

[SOUNDS OF CUTLERY]

CURWOOD: Don't need a knife for this. Oooh!

[FORK SCRAPING PLATE]

CURWOOD: OK, this is not your fried mackerel. This is amazing mackerel. It literally melts in my mouth, and yet it has that little kick that mackerel is, a little sense of oil and ocean and effort or something that is in that.

SEAVER: The taste of vigor. These are active strong beautiful dart like fish that can swim at ungodly speeds. Wow, are they amazing in water and amazing out of the water.

You know, when we go to the fish market it's so important to just ask what's the catch of the day, to participate in a...to behave in a sustainable manner once we walk through the door. If we come in with our own, carrying our own demands of fishermen, of the fish market, of the oceans themselves, demanding only what we're willing to eat rather than asking of them what they're willing and able to supply, we walk out with the best piece of fish that we can. But in order to do that, in order to really enjoy this fish we have to practice liking them. We have to practice understanding and knowing their flavors and their their charisma and their character, and we're not accustomed as a culture to liking mackerel or liking sardines even any more. Mackerel was once the most important valuable and favored fish in all the land. If we shipped the salt cod overseas, it's the mackerel that stayed in the kitchens here.

[SOUNDS OF CUTLERY ON PLATES]

SEAVER: Mmmmm, actually pretty good.

CURWOOD: Barton Seaver's new book is called "American Seafood: Heritage, Culture and Cookery From Sea to Shining Sea". Barton, thank you so much for this, well, delicious encounter.

SEAVER: It is such a pleasure, and what a way to end with a little jazz and a great meal.

[MUSIC ON THE VICTROLA: King Oliver and his Creole Jazz band/Louis Armstrong, “Alligator Hop,” on King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band: Alligator Hop, composed by King Oliver, Gennett Records]

Links

American Seafood: Heritage, Culture & Cookery from Sea to Shining Sea

Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch helps consumers choose sustainable fish

Barton Seaver met up with host Steve Curwood at Portland, ME’s Harbor Fish Market

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth