It’s Raining Viruses, But Don’t Panic

Air Date: Week of February 16, 2018

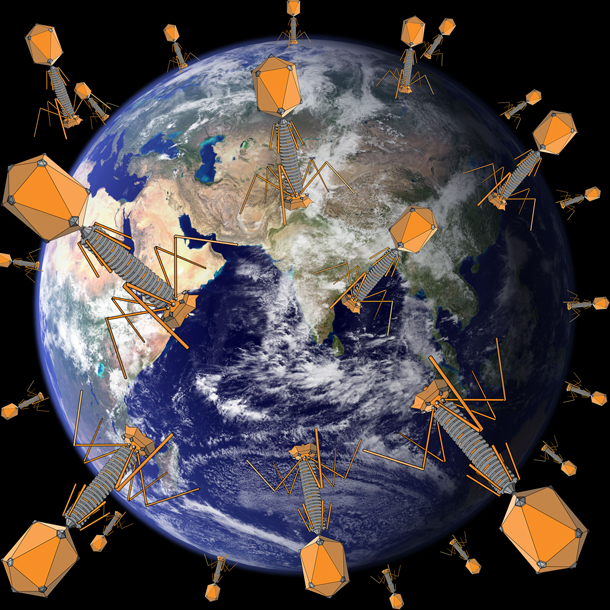

Viruses can travel for thousands of miles around the Earth via dust clouds and marine aerosols, a new study says. (Image: LOE, composed from Earth image by NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and bacteriophage model by Adenosine, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

Untold numbers of viruses are swept up along with dust and water vapor, and a new study shows they travel in the atmosphere for thousands of miles. Microbiologist Curtis Suttle of the University of British Columbia tells host Steve Curwood there’s no need to panic as the vast majority of viruses only infect microbes, not humans. Indeed, these tiny packets of nucleic acids with a protein coat are actually vital to life on Earth, and may even be important for any extraterrestrial life as well.

Transcript

CURWOOD: This flu season is one of the worst in recent years, and we’ll have more on the need for a universal flu vaccine later in the broadcast. Influenza is a virus of course, and must have a host to survive. Fortunately it is a rare virus compared to those that constantly rain down from the sky. Yes, new research shows billions of viruses hitch rides for sometimes thousands of miles in dust clouds and water droplets whipped up by wind. Almost all of these sky-borne viruses are harmless to humans, and even the small number of flu viruses in the sky don’t pose the same dangers as sneezing people and infected door knobs. Curtis Suttle co-authored a study based on data collected in Spain and published in the International Society for Microbial Ecology Journal. He teaches at the University of British Columbia. Professor, welcome to Living on Earth!

SUTTLE: Thanks, Steve. It's a pleasure to meet you.

CURWOOD: So, the first thing I want to know, Professor, is how concerned should we be about all those viruses traveling so far and swirling up there in the atmosphere?

SUTTLE: Honestly, I don't think we really need to be concerned at all. These are bacteria and viruses which are not pathogens of humans. These are essentially the microbes that exist everywhere on the planet.

CURWOOD: What about the flu?

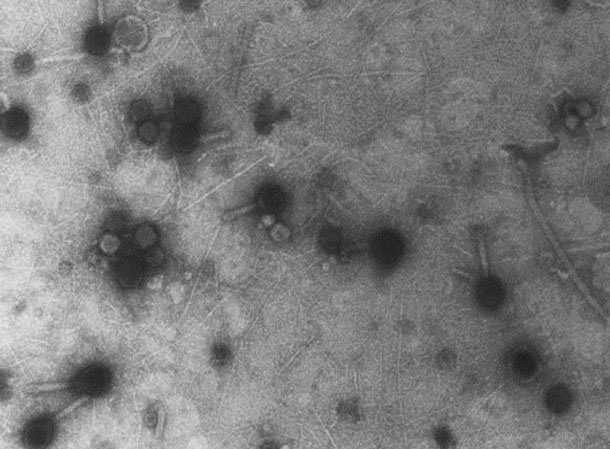

Transmission electron micrograph (TEM) of virus particles in seawater. These get swept up from the surface of the sea to high in the atmosphere, where they can be swept around the Earth. (Photo: Curtis Suttle)

SUTTLE: So, things like influenza, you know, viruses which infect humans certainly they're of concern. So, if we get the wrong virus that's absolutely something we need to be concerned with. But the viruses that we see circulating high up in the atmosphere, the things that they're infecting almost exclusively are other microbes, primarily bacteria, and so one of the things that's really important to recognize is though there are bad viruses that will make us sick because every time you step outside, you're literally inhaling millions of viruses, right, that go into your body. If you take a swim in the ocean, just the amount of water that you take into your mouth would be the same amount of viruses that would be somewhere between the population of Canada and the United States, probably somewhere between 30 and a couple of hundred million viruses that you would ingest, and those viruses don't make us sick, in fact, they're just part of the natural ecosystem. The vast majority of viruses on this planet, the host organisms that they’re affecting are other microbes.

CURWOOD: Well, that makes me feel better. By the way, what is a virus exactly?

SUTTLE: So, viruses are obligate pathogens. They can only replicate by infecting living organisms. They're pretty simple by many standards, they essentially have a protein coat which surrounds some nucleic acids and when they find a suitable host organism, and they're usually highly specific, so they infect only one type of host, then they will introduce that nucleic acid into the host and they will begin to grow.

A researcher with a microbe collector system at the Astrophysics Observatory of Sierra Nevada (Spain). On the left is a wet collector (covered) and on the right is a dry collector. (Photo: courtesy of Isabel Reche Cañabate)

CURWOOD: So, how many viruses are coming out of the sky every day?

SUTTLE: Yeah, what's really remarkable is if we go up above the planetary boundary layer, we will typically find close to a billion viruses on average, every square yard per day that are settling out of the atmosphere, and so when I say above the planetary boundary layer we're talking about elevations say of 9,000 feet or 3,000 thousand meters or so, so above that layer, so high up in the atmosphere. Even that high up, we're seeing these massive amounts of viruses, and if we come down to the surface, like, if you're in a city or in Boston or something like that, you can be sure that there's a lot more viruses that are settling out of the atmosphere than a billion per square yard per day.

Transmission electron micrograph (TEM) of bacteriophage viruses attached to a bacterial cell wall. (Photo: Dr. Graham Beards, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: Professor Suttle, how is it that viruses can travel so far when they get up into the atmosphere? I mean, your paper talks about them, maybe they can even circle the planet!

SUTTLE: You have these particles, these aerosols that are swept off the surface of the ocean or the surface of land, in this case in North Africa, many of them make their way up high into the atmosphere, and once they're that high in the atmosphere and they're so small, they essentially can blow around unimpeded for long, long distances. You know, it's even been speculated that because there are so many out there that maybe there's actually organisms that this is their home, right, that they're suspended up there above the planetary boundary layer.

CURWOOD: So, what would they be doing for food?

SUTTLE: Well, there's all this dust, for example, so the microbes, that's what they need. They need sort of organic material that they can grow on, and there's lots and lots of particles. So, if they were swept high potentially they could be growing on organic material. And also off the surface of the ocean, there's all these aerosols that are traveling high up into the atmosphere and so, I mean, nobody has demonstrated this yet, but I mean it's conceivable that they could be living up there.

CURWOOD: What's the role that viruses play to life on Earth and the evolution of life here. If they can travel like this everywhere, what does that mean?

SUTTLE: Yeah, so, what I always like to think about is that for the first three-and-a-half billion years that life has been on Earth, it was entirely microbial, and so there really were only bacteria and another microbe called Archaea and the viruses which infect them.

Spain’s Sierra Nevada Mountains before and after a dust intrusion event covered their snow-capped peaks. (Photo: Joshua Stevens / NASA Earth Observatory)

And so, viruses were the predators in the system, and the only predators in the system, and multicellular life really didn't come on the scene until a few hundred million years ago. So, for almost the entire existence of life on the planet, the whole ecosystem has been microbial. And so, viruses and the organisms that they infect are extremely highly coevolved. And as part of that process, viruses are really really good at moving genetic information around. And so, in fact, the original field of biotechnology was the result that you could use a virus and you could move genetic information from one organism to another. You know, the original genetic engineering, if you like, was using viruses to actually move genes around among organisms. They do this naturally, and so if we look at our own nucleic acids, our own DNA in our own bodies, a large percentage of it is actually viruses which are still stuck in our genome -- for example, the placenta of mammals contains a protein which was donated from viruses. Some of the major components of our nervous system were actually the result of genetic information donated from viruses. So, viruses are masters at moving genetic information around and as a result of that, they've been absolutely crucial to the evolution of all organisms.

CURWOOD: Interesting. Now, these viruses get lofted up into the atmosphere. If they can get up so high, could they, well, could they be getting into space?

Curtis Suttle is a professor at the University of British Columbia (Photo: University of British Columbia)

SUTTLE: Absolutely, and so it's interesting, we’ve done work with NASA and the Canadian space agency before and when I have served on these committees for years and years and years, I’d say, “If we want to look for life on other planets, we should probably be looking for viruses”, because theory tells us that if we have living organisms, we'll always have these kind of parasites and pathogens they replicate on. They are by far the most abundant biological entities on Earth and presumably elsewhere as well, so you typically would find 10 times as many virus as the organisms that they infect, and because they are so small and they aerosolize so high up into the atmosphere and we have technologies where we can really detect a single virus particle, and so I've often argued that if you're looking for life on other planets, what we should be doing is going into the atmosphere and seeing if we can detect anything that looks like a virus because they're likely going to be there in the highest abundance and it would be absolutely indicative of life.

CURWOOD: Curtis Suttle is a virologist and teaches at the University of British Columbia. Thanks so much, professor, for taking the time.

SUTTLE: Thanks. It's been absolutely my pleasure.

Links

EurekaAlert!: “Viruses – lots of them – are falling from the sky”

Journal article: “Deposition rates of viruses and bacteria above the atmospheric boundary layer”

University of British Columbia Professor Curtis Suttle

Co-author Isabel Reche Cañabate of the Universidad de Granada

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth