Wasting a Wetland With Trash Ash

Air Date: Week of April 27, 2018

The Wheelabrator Saugus waste-to-energy plant. (Photo: Fletcher6, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 3.0)

In the 1950s and 60s landfills were often sited in wetlands, land too soggy for farming or houses. That use would be illegal in the US today and many have been shutdown. However, the Massachusetts Department of Environmental protection recently gave the green light to uncap part of a waste incinerator landfill in an estuary north of Boston and add half a million more tons of toxic ash. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb reports.

Transcript

CURWOOD: There are some 1000 waste incinerator landfills across the country, many built in the 1950s, 60s and 70s and sited in marshes and estuaries, then seen as a good spot to dump trash, since they were useless for housing or farming. Landfills that take toxic fly ash from waste incinerators wouldn’t be approved there today, since we understand how critical wetlands are as wildlife habitat and buffers from coastal storms. But many have been grandfathered in, including a 1950’s landfill in Saugus, Massachusetts, slated for closure in 1996, but still operating.

Now the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection has given the green light to allow an additional half million tons of carcinogenic fly ash and bottom ash to be dumped there. It’s a leaky unlined landfill, sitting in an estuary, in an area prone to flooding. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb has our story.

[WAVE AND WATER SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: In the first week of March 2018, when the moon was full, a Nor’ Easter dumped torrential rains on the coast north of Boston and each high tide brought a new round of flooding for communities there. Revere Resident, Kelly Lampedecchio shares videos of the flooding in her neighborhood on Facebook.

[SOUNDS OF SPLASHING WIND AND RAIN]

LAMPEDECCHIO: Ok, we’re at high tide.

The Wheelabrator Saugus waste incinerator and landfill are located inside the Rumney Marsh Reservation, near the Atlantic Ocean. (Image: Google Maps)

BASCOMB: The water is ankle deep in her backyard. Out front, the street is completely submerged and water creeps up the front steps towards her door. Every house on the street is sitting in water.

LAMPEDECCHIO: The guardrail is completely gone. That’s a dock that floated over from the boatyard. The neighborhood has totally disappeared.

BASCOMB: It’s a lot of water but Sandra Hurly Jewkes and other residents of Revere say they are used to flooding here.

JEWKES: When we get a flood tide here this house becomes an island. It happens, I’m going to say, 5-7 times a year.

BASCOMB: Sandra called me during the storm from her mom’s house, which sits on a narrow spit of land between Rumney Marsh and Massachusetts Bay – the Atlantic Ocean. She says three generations of her family have lived here, in the house her grandfather built.

JEWKES: It’s a beautiful estuary. We have all kinds of birds that nest here. We have turtles, we have seals that come in the river. I mean, it’s beachfront property, it just comes with the downfall of having a trash incinerator across the street.

BASCOMB: That trash incinerator – and the landfill next to it – belong to a company named Wheelabrator Technologies. They own more than a dozen waste facilities across the country.

JEWKES: When the tide comes in and we get these flood tides the landfill and Wheelabrator become an island also, they are cut off from land. It’s water on both sides. So the water is literally lapping right up on the landfill itself.

Part of the Wheelabrator Saugus waste incinerator. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: And it’s the landfill that really concerns local residents like Sandra. It’s the repository for fly ash and bottom ash – that’s the material that doesn’t actually burn up during waste incineration. It contains a cocktail of heavy metals and toxic chemicals – mercury, cadmium, arsenic, lead, and dioxins. For every 4 tons of trash burned, 1 ton of ash is left behind and it has to go somewhere.

[AMBIENT SOUND OF WAVES, PLANES OVERHEAD]

BASCOMB: Elaine Hurley, Sandra’s mother, stands in a restaurant parking lot in Revere overlooking the landfill. Revere and the surrounding cities are working class, industrial communities. Elaine says she remembers back before there were scrubbers on the incinerator when all the toxic chemicals went out the smoke stack and straight into the air, a stone’s throw from her home.

HURLEY: When they started burning the fly ash would come in my house. On the windowsill it was like a black soot all the time and you run your finger it was like greasy. It actually ate the paint off the side of my car that was parked towards it.

BASCOMB: Elaine Hurley says she’s relieved to have cleaner air but concerned about what the chemicals that ate the paint off her car could do to the marsh if they leach out of the landfill.

HURLEY: We’ve gone over there, we’ve videotaped the marsh where the water leaches out. No vegetation. It’s all dead. So, what’s the affects on the fish? You know? What’s the affects on the ducks?

BASCOMB: The landfill sits literally inside the Rumney Marsh, which was declared an area of critical environmental concern in 1988. It’s a vitally important habitat for local and migrating species – an oasis in an industrial area. Planes leaving Logan airport fly over every two to three minutes. A busy highway borders the estuary on one side and it’s surrounded by development on the other sides – houses, gas stations, dry cleaners and so on.

Joan LeBlanc of the Saugus River Watershed Council stands behind a Dunkin’ Donuts next to a pile of lobster traps and looks out at the estuary.

[SOUNDS OF SEA GULLS AND TRAFFIC]

LEBLANC: In the spring when the fish come in, the rainbow smelt, alewives and all sorts of other fish come in from the ocean to feed and to migrate. In the summer time you’re going to see all manner of shore birds as well as migrating birds so great blue herons, snowy egrets. There are also mammals; you have river otters, you have musk, coyotes even sometimes.

BASCOMB: She says any chemical contaminants in the marsh will bioaccumulate up the food chain to eventually contaminate more species, including humans that eat fish.

LEBLANC: These are the type of issues that keep me up at night.

BASCOMB: Research suggests that by the end of the century there will be one and a half to two feet of sea level rise in this area. Joan LeBlanc says sea level rise coupled with frequent coastal storms makes the incinerator landfill particularly vulnerable.

LEBLANC: So, yes we are really concerned about the future. And if there were some kind of major breach in a storm here with this ash landfill and that were to empty into the marsh, I just don’t know how or if you would be able to clean that up.

Located in an industrial community, the Rumney Marsh is designated an area of critical environmental concern. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Most of the landfill is currently capped and from afar looks like a grassy hill, there’s even a bird sanctuary on part of it. But the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection recently gave the green light for Wheelabrator to tear the cap off 39 acres of the facility, so they can dump roughly half a million tons of additional incinerator waste into two valleys originally designed for storm water runoff.

Kirstie Pecchi is director of the zero waste project with Conservation Law Foundation. She says the MassDEP decision to expand the capacity of the landfill is especially egregious because the landfill doesn’t have a plastic liner.

PECCI: Here there just happens to be clay because when you dig a hole in a marsh you’re going to hit clay. There was not a clay liner constructed as far as I can tell, ever.

BASCOMB: The landfill, built in the 1950s, pre-dates the federal law that requires such facilities to have a proper plastic liner. But Pecci says even if this facility did have a plastic liner it would likely still leak.

PECCI: Because the waste is caustic. That’s going to eat through a plastic liner or poke through sooner or later. So even if this were plastic lined I’d say we need to be testing what’s escaping the landfill.

BASCOMB: And that’s another controversial point. This is the only incinerator landfill in Massachusetts where the state does not routinely sample groundwater as required by federal law. Pecci, of the Conservation Law Foundation, says Wheelabrator’s own graphs show that the bottom of the landfill is actually resting in water.

PECCI: So, there’s no way to keep the contamination from entering the marsh because it’s in the water. By definition it’s going to spread through the water.

BASCOMB: To find out why they aren’t testing the ground water as required by federal law I made many requests to speak to Wheelabrator Facilities, the Massachusetts governor’s office, and the Massachusetts DEP, Department of Environmental Protection. They all turned me down. The DEP suggested I talk to the Environmental Protection Agency region 1, which overseas Massachusetts. But the EPA referred me back to the MASS DEP.

Kirstie Pecci of the Conservation Law Foundation speaks to a group of reporters and residents just across the marsh from the Wheelabrator facility. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

In an e-mail, Ed Coletta, a spokesman for MassDEP, explained that instead of taking water samples near the facility they rely on a slurry wall to contain the landfill. They measure the pressure both inside and outside the wall with a piezometer. As long as the pressure is higher outside the wall than inside, they assume any leachate is contained inside the landfill. But resident Sandra Hurley Jewkes says that is no substitute for actually taking water samples near the facility.

JEWKES: I think they aren’t taking them because they don’t want to know.

BASCOMB: Other residents like Elle Baker are frustrated that Wheelabrator spends lavishly to buy good will in the community, but won’t pay for ground water samples or an environmental impact report.

BAKER: If they are willing to write checks for little league, for tree lighting, for other things like this in the community why not for an environmental impact report because that is truly being a good neighbor. That’s truly proving to us the community that maybe … maybe it’s not as dangerous. But they don’t want that to happen. They don’t want to provide that to the community and that’s what’s concerning.

BASCOMB: The only official willing to speak to me about this issue was State Representative Rose Lee Vincint.

VINCENT: I’m determined to make sure that we do whatever we can to, you know, stop this injustice.

BASCOMB: Representative Vincent has introduced legislation to close the Wheelabrator landfill twice.

VINCENT: It’s just so wrong, how anyone can look at it and think it’s not wrong? Instead of realizing it was wrong but now we can try to do something to fix it, let’s try to mitigate and make it safe. What they want to do though is make it bigger, they don’t want to make it safe.

BASCOMB: Vincent says she is worried about the potential health effects on the community where four generations of her family have lived, where she raised her own children.

VINCENT: My children don’t live here but someone’s children live here now. But it’s not just about my children it’s about everyone’s children. Some day some kids should be able to go fishing in that water.

BASCOMB: Because water samples aren’t taken, there’s no way to know what chemical pollutants or how much might be leaking into the estuary from the landfill. But scientists like George Thurston know what they would expect. Thurston is Director of the Program in Exposure Assessment and Human Health Effects at the NYU School of medicine and has served on the National Academy of Science’s Committee on the Health Effects of Waste Incineration.

THURSTON: Our committee, when we looked at this for the National Academy of Sciences, we identified cadmium, arsenic, mercury and lead as some of the components of particles that were of most health concern.

BASCOMB: He says exposure to those types of pollutants can have serious health effects over time.

The Rumney Marsh is an area prone to flooding. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

THURSTON: Cumulative long-term exposures can increase risk of cancer.

BASCOMB: According to the Massachusetts Cancer Registry, the communities near the facility do have elevated rates of certain cancers including leukemia, testicular cancer, and cancer of the larynx. George Thurston says that’s all the more reason to be careful when permitting more potential exposures. And opening up a capped landfill is inherently more dangerous than leaving the facility closed.

THURSTON: But I would say any time you open up one of these capped facilities then that would increase risk of some sort of accident and getting a release. The biggest concerns are when things don’t go as they should and you need continuous monitoring to determine that.

BASCOMB: Thurston has another practical piece of advice – avoid the problem to begin with.

THURSTON: Well, my input on this would be to try to minimize the trash in first place. By emphasizing recycle and composting we can really reduce waste in our society tremendously. Make the facility basically obsolete and unnecessary. I mean that’s … as a society that’s what we should be trying to do.

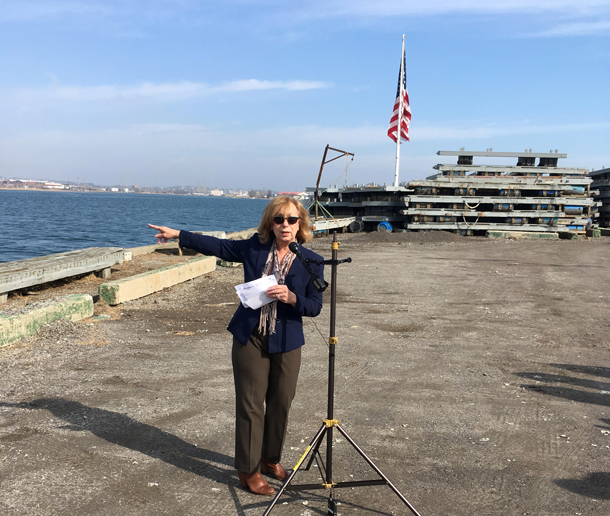

State Representative Rose Lee Vincent points to the Wheelabrator waste incinerator and landfill. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Wheelabrator burns roughly 123,000 tons of municipal waste annually from 10 Massachusetts communities. The company estimates that roughly 80% of the trash could actually be recycled or composted. So consumers have a role in reducing the need for trash incinerators and their landfills.

But for now incinerators continue to burn up our waste and Wheelabrator has the go-ahead to uncap the Saugus landfill and add more toxic ash. Community and environmental groups opposed to the DEP’s decision say all options are on the table to stop that from happening, including appealing the decision in court.

Links

Conservation Law Foundation -about Wheelabrator Incinerator

Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection -about Wheelabrator Incinerator

Wheelabrator Saugus Incinerator-company site

Saugus River Watershed Council concerns about Wheelabrator Incinerator

Statement from Alliance for Health and Environment about Wheelabrator Incinerator

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth