“Pa’lante”: Puerto Rican Resilience After Maria

Air Date: Week of September 21, 2018

Gloria Vasquez points towards the broken and battered trees behind her house. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

It’s been a year since Hurricane Maria made landfall on Puerto Rico, taking roughly 3,000 lives. Most the morbidity came not from the wind and rain of the hurricane itself, but rather from the isolation that followed. Cut off from the outside world, many people died from such conditions as treatable infections, unsafe water and accidental electrocution. But as Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb reports, some communities are looking at Hurricane Maria as a call to organize and become more resilient for future storms.

Transcript

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

We continue our series this week on deadly Hurricane Maria. It’s the one- year anniversary of when Maria slammed ashore Puerto Rico on September 20, 2017.

Some 3,000 people died, but most of those deaths were not from wind and rain but the isolation that followed the storm. The slow aid response after the hurricane left vulnerable people stranded for weeks and months. Many died from treatable infections, contaminated water, or electrocution from downed powerlines. Nine months after Maria I traveled to Puerto Rico and found people that are now looking to each other, not the government, to create more resilient communities and prepare for the next storm.

[DRIVING SOUNDS GPS DIRECTIONS ‘IN HALF A MILE…’]

BASCOMB: To get to Humacao, Puerto Rico you can take highway 53, past McDonalds, grocery stores, and car dealerships. Except for the palm trees, it feels like you could be anywhere in the US. But turn up the narrow, twisty mountain road toward Humacao and it’s a different story. Electrical poles stick out of the ground at awkward angles. Electrical wires hang casually over the road, swaying in a light breeze.

NIEVES: There’s a lot of posts that look like they’re about to fall on people. Trees near highways that look like they are about to fall on cars. And that actually happened.

BASCOMB: Christine Nieves, she’s director of Proyecto Apoyo Mutuo, the Mutual Aid Project, based in a community center at the very top of the mountain in Humacao. Christina says downed power lines and unstable trees are now common here.

Christine Nieves is director of Proyecto Apoyo Mutuo, the Mutual Aid Project, founded after Hurricane Maria to help her community recover from the storm. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

NIEVES: There was a tragedy not too long ago of a young man dying from having a tree collapse on top of him. So you’re still seeing that.

BASCOMB: Christine is petit with wavy black hair and a bright smile. She wears a flowy pink top and long earrings. She left Puerto Rico to go to college at Penn State and then got her master’s degree at Oxford in England. She came back to Puerto Rico 6 months before Maria hit the island and settled here in Humacao, where the hurricane actually made landfall.

[WALKING SOUNDS]

Christine leads the way across a large parking lot to the edge of the mountain and points to a wide green valley below us.

NIEVES: So this is where the eye of the hurricane enters.

BASCOMB: Through this valley?

NIEVES: Yes. It actually made landfall first in this community and all of these mountains.

BASCOMB: Just to describe this area where we are. So right there is the ocean, so that’s obviously where the hurricane came in and just traveled up this little valley in between us here, between the mountain that we’re standing on and that mountain over there and hit these homes right in front of us.

Hurricane Maria travelled up this wide green valley to the interior of Puerto Rico. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

NIEVES: Mmhm, absolutely.

BASCOMB: Were you here during the hurricane?

NIEVES: I was, yeah. My house is actually not too far from here.

BASCOMB: So what did it feel like?

NIEVES: It was chaotic. We prepared so well because we had basically a two-week heads-up. We were prepared from Irma already. We had storm shutters were up. We got water you know, a few days before the hurricane and we filled our cistern. But the actual hurricane, because we were so close we started feeling it on the 19th. One in the morning, we wake up - we start feeling, and hearing, the sounds, and it’s just loud and you can barely hear each other. And that’s when we started noticing that the water was coming in, through all the windows.

These homes in Humacao were some of the very first in Puerto Rico to feel the impacts of the Hurricane. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: into your house?

NIEVES: yeah, through all the windows. Through the storm shutters, it didn’t matter. It was just coming through. And at first we were trying to figure out if we could dry the water and like address that. and then we also started noticing, we have all of our doors, glass sliding doors, and we noticed that the glass was bending inward, so to try to keep it from being pushed into the house, we took all of our furniture and backed it up to the wall, from the door to the wall, like in a chain. It was like, you know, the table, and the chair, and the bookshelf - and everything supported each other all the way to the nearest column.

But that didn’t help. And it was around 4 in the morning that the, skylights exploded in, and then the windows exploded in as well. So there was glass flying. So at that point we actually got into the safest spot, which was a bathroom under the staircase. Dog, cat, three adults, in this tiny bathroom, and just waited. And then we started seeing the water coming in from under the door. It’s just like coming in, and coming in, so we’re like, what do we do? So we just put everything we had and basically everything that got wet we had to toss away.

And it was just, the hurricane came in. So… it was not just water, it was leaves. And then the painting from inside the walls was stripped… scraped off from the pressure. It was like a pressure washer had come into the house and just scraped… not only outside, but inside.

BASCOMB: The paint came right off your walls?

NIEVES: Mm hm.

BASCOMB: That sounds really scary.

NIEVES: Oh yeah. I mean, it was… Luis is a musician, so he was playing - my partner - he was playing the guitar. His cousin is also, you know, his entire family plays some sort of instrument, so he was playing the drums, or the percussion. So we were dealing with it by singing. And we spent the entire hurricane like that. And then once we actually got into the bathroom there was not a lot of space, so we kind of took a nap, sometime in the middle of the night, because you’re so exhausted, and there’s nothing you can do, you know, everything’s getting destroyed. And when we came out at 7 in the morning, we noticed that the, our 2,000 gallon cistern - something had come off, so the entire cistern was getting, was emptying out. And that was just at the moment when the wind was changing directions. So we never felt the calm of the storm, we were kind of… it was basically the wall of the eye, we never got the actual eye.

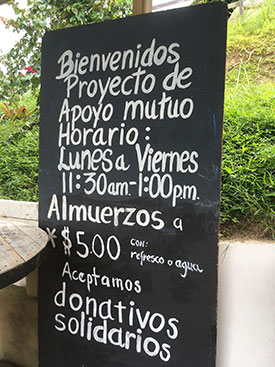

A sign advertises that the Mutual Aid Project accepts $5 “solidarity donations” for lunch Monday through Friday. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

So this was like, that wall of the eye just passed right through us. And we got, because of our altitude, we also got the strongest winds, and some of the storm shutters were actually pulled off of the wall. It was like, it was something so massive that you can’t quite understand it and comprehend it, when you see that something that’s designed to withstand storms didn’t, that’s when you realize, ok, we’re dealing with something that’s beyond the scales that we’re used to.

BASCOMB: So this forest in front of us, I mean, you can see that it used to be a forest, and it still is to some degree, but there are no leaves really on the side of the trees and all of the tops are cut off at the same length, at the same height.

NIEVES: Yeah, so, all of these trees that you see here, they were massive. You couldn’t see beyond them. It was so thick, you couldn’t see the houses even. It looks much better eight months later, because nature is so wonderful and it can bounce back so much faster than human beings can in many ways. But that was actually one of the first things I noticed, that even before FEMA arrived to the island, to Mariana, we were seeing the trees bouncing back. So the trees were faster in their response, than FEMA even.

BASCOMB: It looks like just a big chainsaw went through and just cut the tops off everything and stripped the sides off the trees.

NIEVES: Mm hm, mm hm, yeah. It was like a bomb exploded. And it was also… if you had come here the days after, it looked just like sticks, like matchsticks, just like sticking up, everything looked grey, and it was actually one of the hardest things, because people who live here, obviously, love nature, and it’s one of the reasons I moved back, and it was very hard to see the amount of destruction. It looks like something went through, yeah, and cut them.

BASCOMB: When you came out here the day or two after the hurricane, how did it make you feel to see it look so different, to see the trees just denuded?

NIEVES: when we walked out of the bathroom and went to one of the windows in the house, we were on the bottom part of the house… oh my god, I - Luis, actually, my partner, he started crying, because those were the trees that he grew up with. And it was just a complete feeling of… it was like all the movies that you’ve seen of Armageddon, of destruction, of the end of days, it was like - this is done. And the fact that the communication collapsed meant that also we couldn’t hear the government, but we couldn’t hear each other. All we had was the people next to us.

Eight months after the storm Puerto Ricans were still being injured and killed by falling trees and electrical poles. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: In my 2.5 weeks reporting in Puerto Rico I heard this same sentiment over and over again. Communities were isolate, FEMA and the government were slow to respond, so people turned to their neighbors for help. In many cases the dense forest before the hurricane had blocked their view of each other. People might not even know there was a house across the street or down the way a bit but after Maria turned the lush forest into match sticks neighbors could see each other for the first time and came to rely on one another for help.

NIEVES: the people in this area that are starting to understand that the government is not going to respond and save them, it’s actually going to be their neighbors, having, you know, the machetes ready. Knowing how to disinfect a wound. That’s one of the things that they saw the most, was wounds that could have been disinfected actually ended up in amputations. So they had to cut so many feet off because people were wearing flip-flops in standing water that had infections and they just couldn’t, they didn’t have something like iodine or something that could be easily over-the-counter, anyone can have, disinfecting the wound at the right time. So, it’s that kind of education and preparedness and it’s also community organizing to prepare for the next hurricane.

BASCOMB: Most of the residents of Humacao are older, retirees, who live alone and have been without electricity since the hurricane. Christine takes me to meet one of them.

NIEVES: So, let’s go find Gloria.

[CAR SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: I follow Christine down the mountain to meet Gloria Vasquez at her house a few miles away. A downed electrical wire grazes the top of a car parked in front of her house. She’s standing on her porch watering a potted pepper plant.

Gloria Vasquez standing in her living room. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Buenas!

VASQUEZ: Hello, buenas!

BASCOMB: Como estas?

VASQUEZ: Bien, bien.

VASQUEZ: Let me show her something I am planting.

BASCOMB: Of course.

BASCOMB: Gloria is 70 years old, she wears an oversized red t-shirt and her hair slicked back in a small pony tail. Her house sits on the side of the mountain overlooking the valley. She can see clear to the ocean some 40 miles away. Before the hurricane Gloria says she could only see the dense forest in her yard and an avocado tree taller than her house.

VASQUEZ: the tree, it was so big, tall. It feel me very very bad. And I cry like crazy. Because I don’t think that Puerto Rico is going to be like that, you know.

BASCOMB: You didn’t think it could look like that.

VASQUEZ: No, no. No, I don’t think it’s going to be like that. And still I hurt. I feel, you know, about what happened to Puerto Rico.

BASCOMB: Gloria has accepted her lost trees and the broken landscape but she’s still struggling to deal with day to day life living alone without electricity.

GLORIA: It’s hard. Sometime I sit there and I cry because the light, I need the light, you know? I don’t have no fridge, to cool my stuff, because I got diabetes and I need to put my insulin in the fridge.

BASCOMB: So what do you do?

GLORIA: sometime I take it the lady’s in my neighborhood, Sandra, and then Sandra let me, give me a key to put them inside the refrigerator. She got a generator.

BASCOMB: How do you manage it at nighttime?

Each week a group of volunteers gathers to cook for the community. Feeding their neighbors is a type of therapy. The ladies get out of their lonely dark homes for the day and connect with friends. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

VASQUEZ: By 6:30 it’s starting getting darker so I lock the gate and I lock the door and I stay inside the house, ‘cause you don’t know, you know. There’s a lot of thief here

BASCOMB: A lot of theft.

VASQUEZ: Yeah. They ask me, oh are you there by yourself - no, I’m not by myself. I got a husband. My husband is the police and he is working.

BASCOMB: Gloria lived most of her life in the Bronx. She moved there as a teenager with her family and worked for 50 years, mostly as a hair dresser. She saved her money all those years to retire in her native Puerto Rico where she bought this 3 bedroom cement house.

VASQUEZ: You want to come inside the house?

BASCOMB: Yeah.

[SFX - shuffling into house]

VASQUEZ: This is the living room over here. This is my dining room, and the kitchen. You see, it’s dark. Let me get the flashlight.

BASCOMB: Gloria shows me around her dark house. She pauses at a crèche and a statue of the virgin Mary given to her by her mother.

GLORIA: She gave me this one and this one here. They always here with me. Those are the ones that take care of me.

BASCOMB: She points out framed pictures of her grandchildren and her three sons.

GLORIA: That’s my baby boy here when he graduate.

BASCOMB: How old is he now?

VASQUEZ: He’s going to be 40. And that’s me when I graduate from beauty school. Midway Beauty School in New York.

BASCOMB: In her tidy kitchen Gloria has a few vegetables on the counter, a gas stove, a refrigerator empty but for a bottle of maple syrup, and a small red cooler on the floor where she keeps perishables like milk.

VASQUEZ: But I don’t buy no meat, because meat is getting worse quick.

BASCOMB: It goes bad quickly.

VASQUEZ: yeah

BASCOMB: What do you eat then?

VASQUEZ: If I want to eat something, I go into the store right there, I buy whatever I want to eat, and then I bring it. Today I’m gonna eat verdura.

BASCOMB: vegetables

VASQUEZ: Yeah. This is my dinner for today.

BASCOMB: Eggplant and plantain

VASQUEZ: eggplant, banana, and potato. That’s my dinner and my lunch, is going to be today. And this, hamonia.

BASCOMB: That’s like spam.

Maria cooks up chunks of pork for lunch at the community center in Humacao. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

VASQUEZ: Yeah, spam. And then I cook it and eat half, and I leave the other half for later. That’s the life here. Hard, hard. But what I gonna do?

BASCOMB: That’s the life for most of the residents in Humacao. The majority of people here are elderly, living alone, and without power. That isolation can be depressing and deadly. But since Maria hit locals are looking to each other for solace and sustenance.

[DRIVING SOUNDS]

The next day I drove the twisty road back to the mountain top community center in Humacao. Half a dozen older women have gathered today to cook for their neighbors, as they do each week, Monday through Friday.

There’s a sign out front that indicates when they’ll be cooking and says ‘aceptamos donativos solidarios’ we accept solidarity donations. For five dollars any one can buy a home made lunch of rice, beans, and meat. Maybe some fruit if one of the ladies has extra papaya or pineapple coming up at home. Today a woman, ironically named Maria, is cooking up chunks of pork.

[SIZZLING SOUNDS]

MARIA: I like to make the meat soft and nice and tender. Would you like a bite?

BASCOMB: it’s very good.

MARIA: it is, it is. rice and beans… oh gosh we’re eating good here.

BASCOMB: Maria says coming here to feed the community is a type of therapy for her. She gets out of her lonely dark house for the day and cooks with her friends. They chat about family and argue like sisters. Life feels normal again.

This theme of working together and resilience is everywhere in post- Maria Puerto Rico.

Lunch is served! For $5, anyone can buy a lunch of rice, beans, and meat. Beyond food, community members can connect with one another and feel less alone. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

About 9 months after the storm a local musician named Hurray for the Riff Raff produced a song in part about recovery on the island. The music video shows scenes of hurricane ravaged communities and tells the story of a young family trying to work through it.

[MUSIC: Hurray For The Riff Raff, “Pa'lante” on The Navigator]

Pa’lante is truncated from the Spanish phrase para adelante, which literally means move forward but Humacao community organizer, Christine Nieves says it means much more than that now.

NIEVES: So, ‘pa’lante’ means we’re going to keep moving forward, we’re going to keep rising, and we’re going to keep fighting. it’s about connecting with the root. we’ll look back at this moment in history and I think it’ll have a huge fork on the road in what it does to the Puerto Rican psyche. The conclusion at the end of this disaster that we’re still living in is that it’s us, we were the ones that could respond. We were the ones that were capable of saving lives, and it was community members that were capable of doing it. So, pa’lante. We keep building, we keep building.

[MUSIC: Hurray For The Riff Raff, “Pa'lante” on The Navigator]

BASCOMB: If there’s any silver lining to the devastation that Maria brought here it might be this: a renewed sense of community, Puerto Rican pride, and resiliency that people hope will keep them moving forward to rebuild and meet the next challenge together.

[MUSIC: Hurray For The Riff Raff, “Pa'lante” on The Navigator]

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth