Saving The Sumatran Rhino

Air Date: Week of November 30, 2018

Sumatran Rhinos have a reddish hue with long shaggy hair. (Photo: World Wildlife Fund)

There are fewer than 80 Sumatran Rhinos left in the wild. They live in isolated island habitats, fragmented by agricultural development. Back in the 1980s scientists tried to breed captive rhinos to save the species, with limited success. But a new coalition is hoping to learn from past mistakes and renew the breeding program. Freelance journalist Jeremy Hance has reported about attempts to save the Sumatran Rhino from extinction, and talks with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Indonesia’s Sumatran Rhino is one of the most critically endangered species in the world with less than 80 individuals left in the wild. Back in the 1980s scientists hatched a plan to save the Sumatran Rhino with a captive breeding program. Nearly everything that could go wrong did go wrong with that program, but now a coalition of conservation organizations, including National Geographic, is hoping to learn from early mistakes and start a new initiative to breed the Sumatran Rhino. Freelance writer Jeremy Hance wrote a series about the plan for the online magazine Mongabay, and he joins me now. Jeremy Hance, welcome back to Living on Earth.

HANCE: Thanks so much for having me today.

BASCOMB: So what got you started with Sumatran Rhino? Why do this series?

HANCE: I first met my first Sumatran Rhino in 2009; I was in Sabah in Borneo. And I went and met a rhino named Tam. And I was told before I met Tam that he was a very sweet and kind of like a giant cat. And I was kind of like, that's ridiculous. Rhinos have this reputation of being very aggressive and grumpy animals, but it's a misplaced reputation. And so I get there, and he is. He's like, he's rubbing up against the bars next to me. He's in this beautiful sanctuary in the rainforest. He's snorting at me, he's whistling at me, and spending time with this animal face to face, I just kind of fell in love and I've been following this story obsessively ever since.

BASCOMB: Well, what does it look like? How is it similar and dissimilar to its African cousins, the White rhino and the Black rhino?

HANCE: Sumatran rhinos are the oldest rhinos on earth. And they're the weirdest. They are the smallest, they have hair, and they're distant related to the Woolly Rhino. And they are the last Rhino in their particular genus. But I think what's really unique about it is just that has this, kind of this flank of reddish hair. Especially when it gets... it loves spending time in the mud. It's a rainforest animal. And then it's just, it's the most vocal of rhinos. And so it will sing to you, and the researchers compare the voices, the sounds that it makes to whales and dolphins.

BASCOMB: We actually have some sounds of the Sumatran Rhino. Let's have a listen.

[RHINO CALL]

BASCOMB: [LAUGHS] So, how many Sumatran Rhinos still exist in the world today? And why are they so critically endangered?

HANCE: Sure. So, the short answer is, no one actually knows for sure how many exist. There are some new numbers that just came out last week from a new program that's been launched, and the numbers were basically under 80. And the reason why they're so endangered is obviously they've been hunted for tens of thousands of years by humans. They're still being poached in the wild for their horns for sham medicine. They've also lost a lot of their habitat to deforestation, but at the most critical reason may just be that there are so few left that they're not mating in the wild and they're not having babies. So, basically, the population gets so small that even though there's some habitat left, they're just not enough there to really replenish the population.

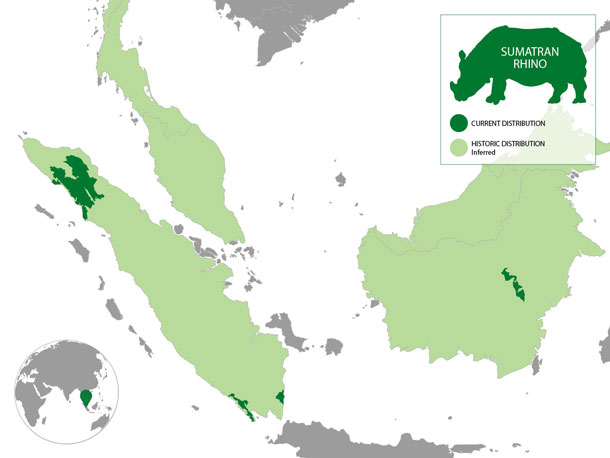

BASCOMB: Right, and as the name indicates, they are from Sumatra in Indonesia, which is, you know, an archipelago of islands, so they're separated geographically. They can't find each other.

HANCE: Yeah.

BASCOMB: Well, so the story you wrote for Mongabay was really about this botched effort to try and save this Sumatran Rhino from extinction. What was the thinking back in the 80s about the best way to do that?

HANCE: Yeah, so in the 80s you had a really interesting development where several of the rhino experts got together in 1984 and they decided...they knew that the rhino was disappearing, they knew that there was a chance of extinction, even then, especially the ones who are really forward thinking and they said, you know, we need to get this animal in captivity. And at that time, they had already successfully done captivity for White rhinos, Black rhinos and Indian rhinos. So, they thought, oh, we can do this. And so they decided to catch a bunch of rhinos, and then put them in various facilities in Malaysia, and Indonesia, in the US and the UK. And what happened from that was a total disaster for about two decades, until they finally achieved some success.

BASCOMB: So, this was ostensibly a plan to breed captured rhinos and save the species, but plenty of them actually died while trying to capture them. And then even more died in captivity. What went wrong?

HANCE: Yeah, a lot of things went wrong. I mean, conservation is complicated, it's messy. You're dealing with animals that at the time no one knew anything about. So, what went wrong is there was mistakes made. Rhinos died in traps. People didn't know exactly how the best ways to catch them, or there was just mistakes...life happened. But then when we got them into captivity for a long time, people were feeding them as if they were a Black rhino or White rhino. They weren't feeding them correctly, so animals would just sort of slowly die in captivity because they weren't getting the right food. They weren't getting the right nutrients.

Fewer than 80 Sumatran Rhinos exist in the wild. They live in fragmented habitats on Indonesian islands of Borneo and Sumatra. (Photo: World Wildlife Fund)

There were also accidents, there was disease. And basically, it took scientists and zookeepers and conservationists about 10, 20 years to really figure out how to feed them right, how to care for them, what diseases were cropping up. And so you have this series of just tragedy, tragedy, tragedy. At the same time, in some ways, even worse, is the whole premise of this idea was to produce rhino babies, right? They were going to get a bunch of rhinos in captivity, they were going to mate like crazy, and they were going to have all these little baby rhinos running around. That didn't happen. They could not get the females to get pregnant. So, for the first 17 years, there was no babies. And then finally, a woman named Terry Roth at the Cincinnati Zoo was able to crack what was going on and was able to produce the first baby.

BASCOMB: And what did she learn? What did she do differently?

HANCE: Yeah, she's a scientist, she works at the Cincinnati Zoo. And she's still there. And she's a really incredible individual. But she basically she knew the history, she was brought into sort of take these two rhinos and get them, you know, last chance to do this. And she basically put the rhinos together. She knew that something was going on with the female ovulation. So, she would do ultrasounds all the time to see why the females weren't ovulating. And they just did this for 40 days. They put the male and the female together and watch what happened. And then she took measurements to see what was going on with the female. And eventually, what she discovered is that a Sumatran Rhino is actually an induced ovulator. And what that means is that there needs to be something to kick off the ovulation in a female, otherwise, they just don't ovulate. So, once she was able to crack that code, then all of a sudden, she was able to actually get pregnancies. And then through time, they were actually able to get a live baby on the ground in 2001.

BASCOMB: Wow, well, so from what I read your article, breeding pairs were captured in these so called doomed habitats. Those were areas that were slated for clear cutting, but after that, a lot of money went in to capturing them, moving them housing them, breeding them, taking care of them for years and years. Wouldn't have been cheaper and more effective just to protect their habitat?

HANCE: Yeah, and that debate was going on at the time, and there was a lot of very well known renowned scientists making that argument, and there was a lot of struggle. And basically, after the captive breeding program went so bad the debate shifted into we need to protect the habitat, we need to set more habitat aside. The problem that we've run into now is, there are so few left that we have basically one of two choices, we can either kind of watch them slowly go extinct, potentially - there might be one or two potential viable populations - or we can catch a few more rhinos and keep trying to keep this captive breeding alive. And neither option is great. It's not an easy situation, but I do think what the captive breeding population has done is they have proven they can do it, and they have given us a chance at ensuring that this animal can survive in the future. Even if it goes extinct in the wild. We might be able to still have Sumatran rhinos in captivity that could then maybe be released in the wild someday.

BASCOMB: So, now conservationists and biologists have a new plan to save Sumatran Rhino. Can you tell me about this Sumatran Rhino rescue project and how is this plan different from what they attempted before?

HANCE: The plan, Sumatran Rhino Rescue, is, it’s a consortium of various conservation groups. National Geographic in involved global wildlife conservation, the International Rhino Foundation, and their plan is to basically do what we did in the 1980s and 90s. Their plan is to go out and catch some more rhinos again. And the reason that they're doing this is because we have only nine rhinos in captivity, only two proven breeders. And we don't have enough genetics to really make sure that this captive population survives. And the rhino is still disappearing from the wild. So, the idea is, if we can go into the field, capture a few healthy females especially, maybe a couple more males, we can supplement the captive breeding program and really make that a success and then ensure that the species doesn't go extinct.

BASCOMB: Well, I have to play devil's advocate just a little bit here. Several millions of dollars...I can't say how many millions of dollars has been spent trying to save the Sumatran rhino. And I mean, there's only less than 80 individuals, they seem somewhat doomed. Why not instead invest that money into anti-poaching units and conservation units and things for the 22,000 African rhinos that are left that maybe have a better shot at avoiding extinction?

HANCE: Sure, and I think so I would say a couple of different things to that. The African rhinos, both the White and Black rhino have a good established breeding population in captivity already. So, if we did happen to lose them, which I don't think we're anywhere close to losing the White rhino right now even as bad as a poaching is and that is a human tragedy and a tragedy on a large scale. So, I'm not trying to diminish that.

A baby Sumatran Rhino. Sumatran Rhinos are smaller than their African cousins with long shaggy hair. (Photo: Cincinnati Zoo)

The other thing I would say is that the Sumatran rhino represents this distinct genus, this wonderfully weird throwback that a lot of people have probably never even. Look it up. Look at this animal. It's weird, it's wonderful, it's googly-eyed. I think that every species in our planet that we have somehow inherited deserves a chance, and I think that the rhino probably plays an ecological role that we don't even realize in the rainforest. Beyond all of that we have a moral obligation, we have a moral obligation not to allow species to go extinct if we have any chance of saving them. And a few million dollars here or there isn't that much money in the grand scheme of things to save a species that has somehow survived tens of thousands of years of humans hunting, and now we have a group of humans who are actually trying to prevent its extinction. So, I think the moral obligation speaks wider than pretty much any other argument I can give.

BASCOMB: Well, how confident are you that this new effort will be any more successful?

HANCE: I'm cautiously optimistic. I'm cautiously optimistic because I know the individuals involved and I know what they're striving for. I wish that this had happened 10 years ago. I wish that we had more rhinos, in captivity. You can do all the wishes in the world, but I wish that the situation was somewhat different. But I do think that the challenges are huge. And another reason I guess I would say, I'm cautiously optimistic is that we've done this before. The European bison went extinct in the wild, down to 12 animals, and they brought it back and now there's 4,000 in Europe. So, we can do this. This is not impossible. We just need the money, the support and collaboration, I think. Things are going to go wrong. It's not going to go perfect. I'm sure that there will still be tragedies to go. But I do think that having met some of these baby animals, when I visited the sanctuary in Indonesia, and met the people who take care of them every day. That's what makes me optimistic.

BASCOMB: Jeremy Hance is a freelance reporter and senior correspondent for Mongabay. Thanks so much for talking with me Jeremy.

HANCE: Thank you so much for having me. You have a good day.

Links

Mongabay Series on the Sumatran Rhino

National Geographic | "First wild Sumatran rhino captured in urgent bid to save species"

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth