Heat Wave Scorches Nature Down Under

Air Date: Week of February 1, 2019

Due to the hot, dry temperatures caused by heatwaves, fires are rampantly appearing across Australia. (Photo: fvanrenterghem, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Australia’s plants and animals evolved to withstand a hot climate, but the extreme heat that the continent has recently been hit with is far from normal. In recent weeks about a third of the bat population has died, water sources are becoming oxygen-depleted, and Australian forests are a tinderbox. Joining our host Bobby Bascomb is Dr. James Watson, Professor at the University of Queensland Australia and Director of the Science and Research Initiative at the Wildlife Conservation Society in New York.

Transcript

BASCOMB: As parts of the US dealt with a polar vortex and record cold temperatures Australia is in the grip of an unprecedented heat wave. And Steve, we’re not talking 90 or 100 degrees but more than 120 degrees in some parts of the country for days on end. And, as you know, Australia is no stranger to hot dry weather of course.

CURWOOD: Oh, that’s right…

BASCOMB: But this heat wave is something out of the ordinary even by Australian standards. I have a friend, Kerri Verbart, who lives in Adelaide, Australia on the south coast.

CURWOOD: Now Isn’t that where the good Australian wine comes from?

BASCOMB: Yes, that’s right, exactly. And normally, Adelaide has a lovely Mediterranean climate, warm and dry for sure but Kerri told me that people there are really struggling to deal with 120-degree heat.

VERBART: It just feels so hot. I know that sounds crazy but it’s just like a sauna or a dry oven or a sauna with a hair dryer blowing on you at the same time. Or a big hot fan blowing on you. A lot of people didn’t go to work including my husband who works on building sites. Well, he went in the morning and was home by lunchtime.

CURWOOD: Man, that sounds pretty miserable.

BASCOMB: Yeah, but you know there are always people who can make lemonade out of their lemons.

VERBART: People were frying things in frying pans, baking cookies you know in a frying pan on the pavement. You can actually cook.

CURWOOD: Wow

BASCOMB: The way Kerri describes life there right now it really reminds me of living in New England in winter, as we do. She says the Red Cross and emergency personnel check in on the elderly to make sure they are doing ok. And, people are generally just grumpy and mostly stay inside and hibernate.

VERBART: Most people are in their homes with the air conditioning on. You didn’t see many people at the pool either so obviously, many people are thinking it’s even too hot to go to the pool. Shopping centers are what are busy at this time because they’ve got fantastic air conditioning systems. So, if people at home their air conditioning is struggling they seem to flock to shopping centers, cinemas, and places that have great air conditioning.

BASCOMB: So, it’s certainly uncomfortable for most people but nearly everyone has air conditioning or access to a place that’s air-conditioned. The real victims of the heat wave are Australia’s many plant and animal species that are endemic that is, found nowhere else on earth. They’ve evolved with Australia’s mostly hot dry conditions but this unprecedented heat wave has proven devastating even for them. I spoke to James Watson about that. He’s director of the science and research initiative at the Wildlife Conservation Society. Welcome to Living on Earth, James.

WATSON: Thanks for having me.

BASCOMB: So, James, please describe the heat wave and the drought. How does this event compare to what Australia usually experiences?

WATSON: Well, this is the worst on record. We've never had a heat wave like it and it's extensive so, it covers the entire continent. And, it's just really hot. So, for those two factors, it's really unique. No time in the last, you know, climate measurements have we seen a heatwave go across the continent, from Tasmania to Western Australia, to far north Queensland. And then the degree of heat is just enormous. We're getting up to 50 degrees Celsius in some of the major cities which is just extraordinarily hot. And it's not just for, you know, a day or half a day, it's lasting for a week.

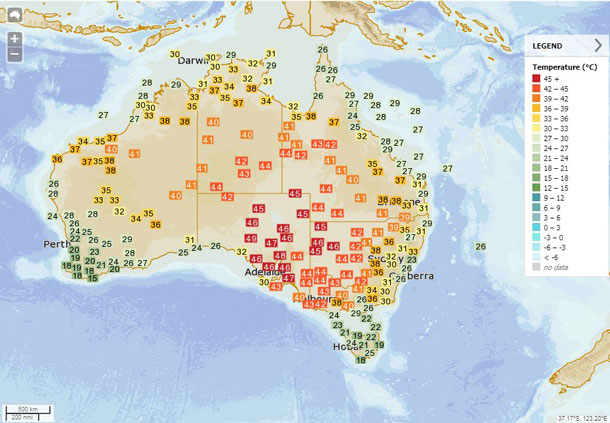

BASCOMB: Yeah, for those of us over here, 50 degrees Celsius is about 122 degrees Fahrenheit. I've seen maps where the whole continent is just red, you know, from the heat map, it's 100% red.

The Bureau of Meteorology in Australia reported record breaking temperatures during the heatwave. (Photo: Courtesy of the Australian Bureau of Meteorology)

WATSON: What's unusual is the Bureau of Meteorology over here had to create new colors for the map. That's how hot it is. So, it's a sad indictment of climate change. Uhm, and, it's, you know, it's obviously going to be the new norm, and it's really affecting both people and wildlife across the continent.

BASCOMB: Of course, the vast majority of the population of Australia lives along the coast and in the middle of the continent is mostly desert or very arid. To what degree is desertification, a concern if this kind of drought and hot temperature persists?

WATSON: Oh, it's massive. It's a massive issue. The hot weather is one thing, it's the land clearing which is causing desertification. It's actually because you're removing trees and nothing's being replaced by trees because it just simply too hot, you get grasslands which then die, which then the deserts you know, so it's a huge issue and it's one that Australia is going to be increasingly facing. So, it's- the heat wave plays an extraordinarily important role in this because it kills the vegetation that is remaining but the most important thing is to put vegetation back there in the first place or stop clearing vegetation. That- if you want to stop the desertification you keep intact ecosystems intact and that means that the soil becomes stable and the deserts don't increase.

BASCOMB: How is the heat wave affecting different ecosystems there, for instance, forests?

WATSON: There's fires occurring Tasmania right now in forests that have never been burnt. Which is terrible because they'll never recover. These are endemic World Heritage forests, these cool, wet forests that you'll find in the southwest. And, you know, endemic species of tree and shrub and birds and mammals are actually all getting wiped out as a consequence, because they're not adapted the fire. In other parts of the continent, we're seeing more fire, uhm, not to that extent. But what is interesting is that because of logging and because of degradation of the forest by human activities, such as roads and farming, building urban settlements in the middle of forests, means a fire can access these forests in ways obviously, they wouldn't naturally. And, that is making these forests less resilient to fire and when it's warm and dry it means you just get more and more fire. So, if you look at a map of Australia right now, there is just spot fires everywhere across the continent because this kind of drawing effect, because of the fact that it's really easy to set fire to a forest due to electrical storm or something like that. And the fact that these forests are just really dry and non-resilient, it means they burn really easily.

BASCOMB: And, you said Tasmania many has so many endemic species, that’s species you don't find anywhere else in the world. And if they're not adapted to fire, as you said, I mean, are you looking at extinctions there?

WATSON: Oh, yes. Yeah. And we're talking about extinction of plants that evolved in Gondwana period, you know, 60 million years ago. Some of these plants are incredibly unique, and you know, adapted to these cool wet climates, you only really get in the southern hemisphere in places like Chili, Tasmania, and New Zealand. But, so, the species in Tasmania have obviously isolated from those other two continents for a long time. So, they're all unique. They're all different species. And, they're not fire adapted. And, so, any fires bad. And if you look at some photos, there's, you know, it's all on the way, if you just Google Tasmanian fires, you will see huge swathes of the World Heritage Area just cindered black. And, the fact is they won't recover. These species have no way to recovering. So, something will come back, but it won't be the ecosystem type that we have experienced for the last 60 million years. So, it's very sad.

BASCOMB: I understand a lot of animal species are also really struggling with the drought and the heat. Can you tell me about some of those?

WATSON: We're seeing evidence of this heat wave affecting species all around the continent. Right now, in a place called Menindee Lakes, we have thousands and thousands of fish just bubbling to the surface of the lakes because of the heat, because of the low water levels, this system is unlikely to recover for a very, very long time, if not at all. In other parts of the continent, we're seeing things like flying foxes, hundreds and hundreds have been falling out of trees and colonies simply because they're cooking in the tree. They're getting to a temperature that they just can't survive, so they literally die in the tree and fall on the ground in their thousands. Again, entire colony structures have been wiped out by this heat event.

It has been reported that one-third of Flying Fox populations in Australia have been lost due to severe heat exhaustion during the heatwave. (Photo: Amaury Laporte, CC BY-SA 2.0)

BASCOMB: Of course, these animals are native to Australia and no stranger to hot, dry conditions. Will they be able to bounce back from these types of hits to their population?

WATSON: Well, it really depends. I mean, yes, they naturally adapted to hot, dry conditions. And of course, they've gone through extreme events in the past. This is very unusual; this hasn't been set on record. So, you know, whether they can survive this particular extreme event is yet to be seen, but they should have the resilience in their populations to survive. The problem is that we haven't got natural populations of species anymore. In Australia, I think it's the world leader in terms of mammal extinctions around the world. We have decimated our landscapes because of land clearing, especially in the south and the east. So, to answer your question, we don't know. We don't know. What we do know is that many of these populations are likely to struggle.

BASCOMB: What about freshwater ecosystems? What's going on there?

WATSON: It's a real disgrace, to be honest. What we have in the Murray-Darling river system, which is our big river system in southeastern Australia. It's been running very low for many, many years, because of irrigation. Because there's all the environmental flows have been going to the farmers. You know, I used to live out in one of those rivers. And, you know, I went out there the other day, and it's, you know, literally- I remember a river that I could never touch the bottom of the river. As much as I could dive, I could never touch the bottom. Now it's literally knee-high water across the entire river. You know, tens of meters of water across the river system is gone. Obviously, fish have to survive in that system. And when there's a heatwave event, it just gets too hot. There's not enough water and the fish die. And they get toxic blooms, which kills them by poisoning. And the consequences are these kind of massive fish kill events. And obviously, it's very distressing for local people. It's very distressing for the indigenous people who live out there. And it's a very sacred area for Australians, you know, Indigenous Australians who are seeing their entire system die.

BASCOMB: So, the heat wave is just exacerbating a situation that already existed.

WATSON: That's right. I mean, yeah, the water is just much, much hotter. You know, fish can't live in really hot water. So, it looks like a massive problem. It looks like a problem that, you know, it's hard to overcome, how do you solve climate change? Well, you know, simply get your house in order when it comes to habitat management.

BASCOMB: I have a friend in Australia who told me that she sees buckets of water all over the place that people leave out to help animals. And, is that a good idea? I mean, does it even help? Or, is it just a drop in the bucket? If you'll pardon the pun.

In an attempt to assist wildlife, many people have been putting out water and shade to provide some relief in the heatwave. (Photo: Sunrise on Seven, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

WATSON: I think it's, I think it's good for urban wildlife. Absolutely. You know, like, obviously, you know, when you've got buckets of waters out there, you know, you have other things coming to it. So, where there's invasive species, such as toads, they'll like that, as well, you know. So, you're encouraging the persistence and all nature, not just native nature. But, I think, yeah, this time and place absolutely. I think putting out water is a good thing. It helps birds survive, it helps mammals survive. Putting shade, it means it's cool places for things to sit. And there's also it brings nature to your backyard, you know, which is a good thing for children and you know, yourself to actually just experienced stuff. But, you know, that's a small drop in the wider ocean. 99.9% of species, don't live in cities, or urban areas, or, you know, even townships. They live out in the bush. And, the bush is really where the water needs to occur. And that means we need rain, we need rivers the flow naturally, we need habitat to be in good nick so spaces can move around. That's the trick. You know, and therefore, putting out a bucket of water is a good idea. Voting for a government that actually is progressive on things like climate change, and on doing the right thing for nature is probably an equally good thing to do.

BASCOMB: That’s James Watson, director of the science and research initiative at the Wildlife Conservation Society.

Links

More information on Dr. James Watson

New York Times | “Thousands of Fish Die in 3rd Mass Death in Australian River"

CNN | “Dozens of Wild Horses Die of Thirst in Australia’s Heat Wave”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth