“Hockey Stick” Climatologist Wins Tyler Prize

Air Date: Week of March 15, 2019

Warren M. Washington, left, and Michael Mann, right, are the 2019 recipients of the Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement. (Photo: Joshua Yospyn / Tyler Prize)

Climatologist Michael Mann is the co-recipient of the 2019 Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement, considered by some as “the Nobel Prize for the environment”. In a conversation with Host Steve Curwood, Prof. Mann recounts his research that led to the famous “hockey stick” graph showing rapid global temperature rise, and the ensuing attacks on his scientific research and reputation by climate deniers allied with fossil fuel interests. Michael Mann also discusses his latest research findings and the promising new generation of science communicators.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

The Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement recognizes outstanding scientists. And past recipients have included E.O. Wilson, Roger Revelle, and Jane Goodall. For 2019, two atmospheric scientists share the Tyler Prize: Warren M. Washington, a senior scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, and climatologist Michael Mann, Distinguished Professor of Atmospheric Science at Penn State University. Professor Mann has been a regular guest on this show to explain what’s going on with climate disruption including hurricanes, wildfires, heat waves, and the polar vortex. Beginning in the 1990s, he got attention for developing the "hockey stick" graph that starkly depicts the recent rapid increase in average world temperature. But his climate research has also earned him the ire of the fossil fuel industry. Michael Mann joins us now in our studio. Welcome back to Living on Earth -- and congratulations!

MANN: Thanks so much, Steve. Really appreciate that.

CURWOOD: So, you're famous research-wise for doing what some folks would call paleoclimate work. That is, you look back at what happened hundreds, thousands of years ago to say what might be happening in the future. Talk to me about that. And why did you become intrigued with that?

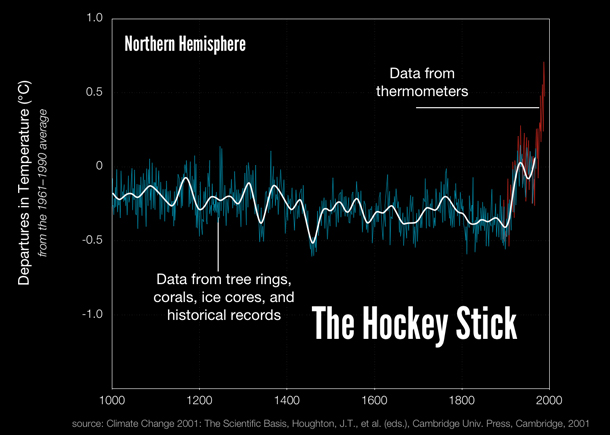

The famous “hockey stick” graph, showing time reconstructions [blue] and instrumental data [red] for Northern Hemisphere mean temperature. In both cases, the zero line corresponds to the 1902-80 calibration mean of the quantity. Raw data are shown up to 1995. The thick white line corresponds to a lowpass filtered version of the reconstruction. (Photo: Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis, Houghton, J.T., et al. (eds.), Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 2001)

MANN: Yeah. So what we did is we used all the natural archives that we could get our hands on: tree rings, of course, tell us something about past conditions related to tree growth -- rainfall and temperature. So we can glean information about climate from the thickness and even the density of the rings in tree cores from sort of continental, extratropical locations. Tropical trees aren't useful for tree ring research. So you're only getting information really from the extratropical continents, and that's not the whole planet, right? So you need to fill in those gaps. Well, we do that by using other data like ice cores, which come from high latitudes or even in some cases the tropics, at very high elevations, like Mount Kilimanjaro or in the Andes. So now you're starting to fill in those gaps. You've got the tropics, you've got the polar regions, then the oceans; well, we can turn to corals. The calcium carbonate skeleton of a coral contains, typically, annual growth rings. And we can look at the isotopes of oxygen in those growth rings; that tells us something about the seawater that that coral was growing in. And so what our project was about was taking this increasingly rich information coming from scientists around the world producing these different kinds of records, and assimilating them into a single reconstruction of past large-scale temperature patterns around the globe. Now to us, the most interesting thing about those reconstructions was what we could learn about the regional patterns of past climate -- the El Nino phenomenon; what happened during the largest prehistoric eruptions. It was those sort of regional patterns that we were really interested in, what they could teach us about climate dynamics. But what ended up becoming by far the single most prominent aspect of that research was what happens when you average over all of the regions, you average away a lot of those interesting details. And you come up with one number for each year, the average temperature of the Northern Hemisphere. And we could plot that back in time. And when you do that, what you see is that it was relatively warm about 1000 years ago. And then we descended into the depths of the Little Ice Age, in the 17-, 18-, 1900s; and then we see this warming spike, of the past century. And it is so sharp that it takes us well outside of the range that we see over the past thousand years. So laid on its side, it looks like, you know, the sports implement that we refer to as a hockey stick. And that's the name that it got, and the name stuck.

CURWOOD: So you do this research, you publish this research; the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change uses the hockey stick chart as part of its summary in 2001, big assessment; and you go get a job at the University of Virginia. And then... trouble.

Michael Mann was invited to give a lecture about climate change impacts at the University of Massachusetts Boston on March 5, 2019, by the university’s School for the Environment. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

MANN: Well that's right; you know, I was subject to sort of this crescendo of attacks on the hockey stick, but often on me personally -- efforts to discredit me and thereby, you know, presumably discredit this iconic curve, the hockey stick curve, this symbol in the climate change debate. There, you know, started to be op-eds and editorials attacking the hockey stick and me, in conservative media venues, The Wall Street Journal for example. And all of that was happening about the time I arrived at the University of Virginia. And I'm trying to of course acclimate to this new role, this new job that I had as a professor, I've got to teach and advise students, and I'm juggling all that. But I'm also sort of dealing with the increasing amount of publicity surrounding the hockey stick curve. Pretty soon, I would find myself at the receiving end of attacks by prominent politicians closely tied to fossil fuel interests, like James Inhofe of Oklahoma, who has dismissed climate change as the greatest hoax ever perpetrated on the American people. Back in 2005, the head of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, Joe Barton, a Republican from Texas, very closely tied to fossil fuel interests, tried to subpoena all of my personal emails, and those of my two coauthors on the original hockey stick article; held a hearing, trying to attack the hockey stick. And typically these attacks would coincide with major policy developments. For example, there was an energy bill potentially dealing with climate change that was about to be voted on by the US Congress, and in advance of that Joe Barton, again, used -- or some would say, abused -- his authority as the chair of that influential committee to run a show trial attacking the hockey stick, and essentially go on this campaign of vilification against me and my coauthors.

CURWOOD: So famously, the Attorney General of the Commonwealth of Virginia came after you, and people may or may not think of Virginia as a coal state, but they got plenty of coal out west of Virginia, the fossil fuel industry was very concerned about your research; and the Attorney General came after you. What was the accusation and what happened as a result of those accusations?

MANN: Yeah. So this was Attorney General Ken Cuccinelli, who is often referred to as a Tea Party Republican, elected in 2009; attempted to subpoena my emails using what's known as a civil investigative demand, which exists in Virginia law so that the attorney general can ferret out state waste and fraud. And so what he tried to argue with that the science of climate change is fraudulent -- dismissing of course the overwhelming consensus of the world's scientists -- and thereby arguing that he could use this investigative demand which was really designed to deal with Medicare fraud. But nonetheless he attempted to use this as a cudgel, to go after me and my coauthors, much in the way that Joe Barton before him had done. Again, Ken Cuccinelli, conservative Republican who was heavily funded by some of those fossil fuel interests, including coal interests, which do have an influential role in the state of Virginia.

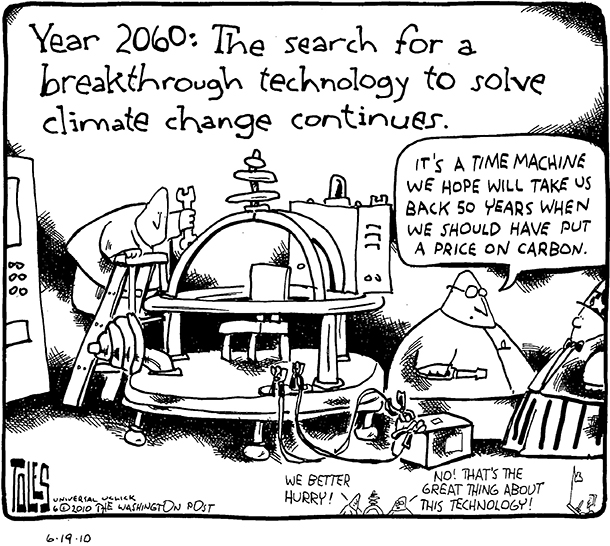

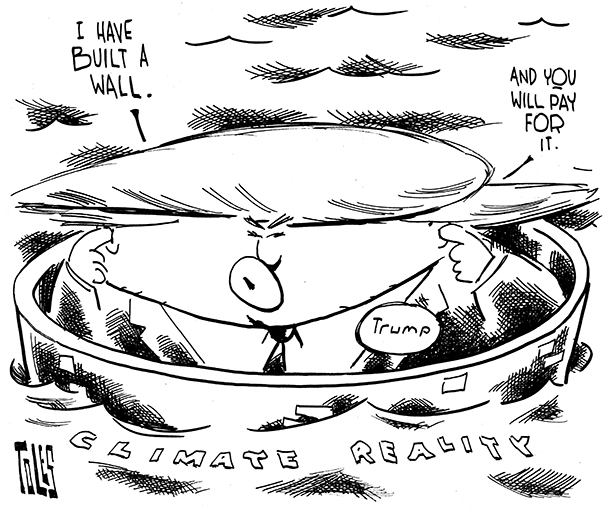

Michael Mann and cartoonist Tom Toles coauthored the book “The Madhouse Effect: How Climate Denial Is Threatening Our Planet, Destroying Our Politics, and Driving Us Crazy”. (Cartoon by Tom Toles)

CURWOOD: This wasn't a small case, I mean, it winds up in the Virginia Supreme Court; if not millions of dollars, hundreds of thousands of dollars being spent on legal fees, and what was the outcome?

MANN: Yeah, that's right. And the University of Virginia was forced to spend millions of dollars defending itself. It was very costly for them and a distraction for everyone. And in the end, it was dismissed by the lower court because they found that in his 40-plus page filing to the court he had failed to show any evidence of wrongdoing on my part, any evidence of any malfeasance at all. And so it was dismissed by the lower court. Cuccinelli challenge that decision, it went to the state Supreme Court, which ultimately rejected his case with prejudice, meaning, they never want to see an attorney general come to the court, come back to the court with something like that again. So that was a battle that we won. It was a battle that was won on the side of science and reason and logic and honesty, but it was just one in many skirmishes in this battle.

CURWOOD: The struggle in the courts of Virginia over your research got you a lot of attention in the United States, but internationally, you became famous, Michael Mann, because of an email hack. Tell me about that story.

MANN: Yeah, you know, there was a fair amount of attention in the US and internationally, drawn to this affair that came to be known as climategate -- ironically, because much like Watergate, the only real indiscretion, the wrongdoing, was the criminal theft of those emails in the first place. But what hackers working with, what were probably state actors, we now think--

CURWOOD: You're thinking Russians?

MANN: There's some evidence that Russia and Saudi Arabia were both involved in this, as a means of sort of thwarting progress at the 2009 Copenhagen summit. So the Copenhagen international climate summit in December 2009 was really the first opportunity in years for international policy action, for an agreement that would really help us tackle the problem of climate change. And fossil fuel interests and state actors working on their behalf, did everything they could to sabotage those proceedings. What they did: they combed through thousands of stolen emails, and looked for individual words or phrases that could be taken out of context to make it sound like scientists had been cooking the books, using words like "trick", which, a trick, in science means it's a clever way of solving a vexing problem. But to the person on the street, you take that out of context, you tell them, Look, these scientists are playing tricks, it's a way, again, to try to take the language of these scientists out of context, to misrepresent what they were doing, and to smear them and discredit them.

CURWOOD: Today, Michael Mann, how afraid are scientists of harassment and difficulties when telling the story of climate disruption?

MANN: I think that that is part of the purpose of these attacks, is to frighten especially young scientists, who might think of becoming more active in the public conversation about climate science and climate change. But in my view, I think it's had the opposite effect. I think the attacks have so enraged the scientific community, this assault on science. And, you know, some would argue that the assault on science that we were dealing with has now metastasized into something larger in our politics today, which is an assault on truth, objective truth, and facts. And if you don't like the facts, there are alternative facts, as we have come to know, that many people are willing to promote. So we've lost sort of this objectivity in our public discourse. In climate change, we saw that years before, we saw that, the thing that we're now seeing writ large in American politics was already happening there. And I think that that was truly distressing to scientists, the idea that the forces of science denial would sort of stoop to the most dishonest of tactics in an effort to discredit science itself. I think that that brought in a whole new breed of scientists who were not only passionate about science, but wanted to help defend it against these attacks. And now there is this cadre of young scientists coming up in the field who are extremely active when it comes to outreach and communication and it's become a very valued part of their identity as a scientist. And so I like to think that the attacks that were intended to frighten away would-be scientist communicators have instead led to a whole new generation of pretty thick-skinned scientist communicators who want to make sure that we have an objective conversation about the science and its implications.

"The Madhouse Effect" features incisive critique of prominent climate deniers. (Cartoon by Tom Toles)

"The Madhouse Effect" features incisive critique of prominent climate deniers. (Cartoon by Tom Toles)

CURWOOD: Let's talk about today. What are your latest findings?

MANN: So I -- you know, most people when they think of me, they think of the hockey stick and they think of paleoclimate. But these days, my scientific interests are more focused on the impacts of climate change -- coastal impacts, understanding how climate change is impacting coastal storms, hurricanes and tropical storms, and how that is combining with global sea level rise to threaten our coastlines, with a focus on, you know, places like New York City that of course, have dealt with devastating recent coastal storms like Superstorm Sandy, unprecedented flooding. How much worse is that going to get? You know, what does the future look like? There's a lot of interesting scientific uncertainty there, particularly with respect to global sea level rise, because that depends on the stability of the ice sheets. And we're starting to learn that the West Antarctic ice sheet, the Greenland ice sheet, may be less stable to near-term warming than we thought. So there's a lot of uncertainty there. But it's not our friend. It means we could be in for far more damaging sea level rise impacts in the future. That's an area of interest to me, because it involves some really interesting science to understand how climate change is going to influence the characteristics of hurricanes, the frequency and the intensity and the size of these storms. There's a lot of really interesting underlying atmospheric physics there. I'm also very interested in the impact that climate change is having on extreme weather events in general, particularly summer weather extremes, like the sorts of droughts and heat waves and floods and wildfires out west that we've seen in recent summers. In fact, 2018 was sort of a poster child for how climate change is increasing many of these devastating extreme summer weather events. And our own research suggests that there are processes, fairly subtle physical processes involved, that are actually exacerbating these extreme weather events in a way that isn't captured in current generation climate models.

CURWOOD: Oh?

MANN: No - it has to do with some fairly subtle features, that have to do with waves in the atmosphere. In fact, in the March issue of Scientific American, I have an article about this phenomenon. It turns out, it's interesting scientifically, because there is actually a connection between these wave phenomena in the atmosphere and sort of the physics of quantum mechanics. And some of the mathematics we use to study this problem actually comes from math that was developed to solve problems in quantum mechanics.

CURWOOD: So you're talking about a new way of looking, really, at resonance, if I were to oversimplify it.

Michael Mann is a Distinguished Professor of Atmospheric Science and the Director of the Earth System Science Center at Penn State University. (Photo: Sydney Herdle)

MANN: Absolutely. What has made these extreme weather events so extreme, like last summer, summer 2018, was the fact that we had these exaggerated waves in the atmosphere. When you look at the jet stream and it wiggles north and south as it crosses the United States for example, those north and south wiggles are associated with high and low pressure systems. And the larger the wiggles, the bigger those highs and lows. Big high pressure gives you the sort of heat and dryness that yields unprecedented California wildfires like we saw this summer. But you get the flip side of that wave, you get the trough, the low pressure back east, and you get unprecedented rainfall. And we saw the wettest summer on record, where I live in Central Pennsylvania; I think Quabbin reservoir in the western part of Massachusetts reached the highest level that it has ever seen. And so what made those events so profound, so extreme, was both the large nature of the waves in the atmosphere that give you those big surface high and low pressure systems, that give you unusual weather, and the fact that they were very persistent, they just stayed locked in place. The ridges and the troughs basically sat over the same regions. That means those highs and lows are sitting over the same place, either baking you, or dumping rain on you, day after day. And that's when you get truly unprecedented weather extremes. That phenomenon, the waves getting larger, is a resonance phenomenon.

CURWOOD: So what should the public do now in response to your latest research?

Michael Mann and Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

MANN: Well, I think one thing that our work and a large family of research in this field has shown us in recent years is that uncertainty isn't our friend. As we begin to understand and better model some of these processes, we're not finding that climate change is less of a problem than we thought, we're finding in many cases that it's worse of a problem. The ice sheets can melt faster; that means we can get more sea level rise sooner than we thought. Climate change is exacerbating extreme weather events in a way that we didn't fully appreciate. But we're seeing play out in real time now on our television screens and our newspaper headlines. Uncertainty is not our friend. If anything, it's a reason for more concerted action. So when the critics say, well, there's uncertainty in the science, and they use that as a crutch for inaction --actually, uncertainty implies just the opposite. We want to take an insurance policy because of the potential for things to be far worse than even our current projections suggest.

CURWOOD: Michael Mann is a Distinguished Professor of Atmospheric Science at Penn State University and a cowinner of the 2019 Tyler Environmental Prize. Professor, congratulations!

MANN: Thank you very much, Steve, it means a lot.

Links

Michael Mann’s article in the March 2019 issue of Scientific American

About Michael E. Mann and Warren M. Washington, 2019 Tyler Prize recipients

LOE’s interview with Mann about climate change and 2018’s Hurricane Michael

LOE’s interview with Mann on the release of his book “The Madhouse Effect”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth