Everglades National Park, a “River of Grass”

Air Date: Week of April 5, 2019

The Everglades National Park provides visitors with a variety of beautiful vistas. (Photo: Lizz Malloy)

Established as a national park in 1934 and a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1979, Everglades National Park is much more than a mere swamp. Only an hour’s drive west from bustling Miami, the 1.5 million acres of the Everglades provides a place of sanctuary in nature for those looking for peace and quiet, as well as a front-row-seat view of wildlife from anhingas to alligators. Living on Earth’s Lizz Malloy went to check out the “River of Grass.”

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

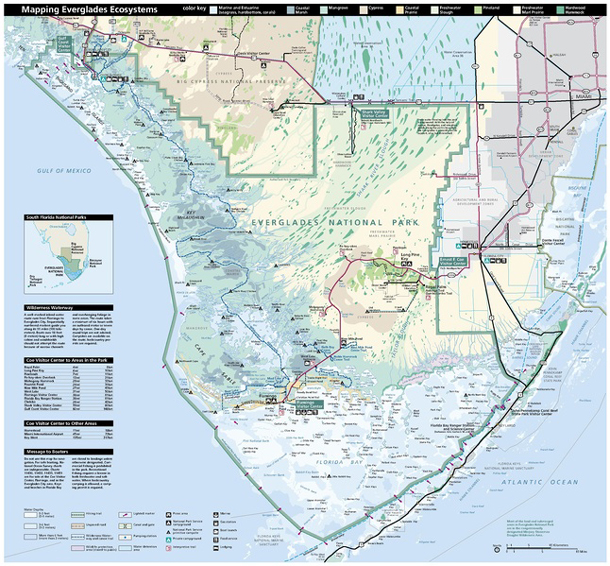

The Everglades National Park in Florida is the third largest National Park in the lower 48 states and contains 1.5 million acres of protected wilderness. And UNESCO names it a world heritage site that’s in danger. The Everglades is often called the river of grass for its vast system of slow moving bodies of water which spread much further than the National Park boundaries. Over the years attempts to fill in and drain these wetlands to build homes and farms have damaged and polluted the Everglades. And, despite conservation efforts, today the Everglades is only about half its original size. Living on Earth’s Lizz Malloy went to visit Everglades National Park.

[MUSIC: Afro Cuban All Stars, “Amor Verdadero” on A Toda Cuba Le Gusta, World Circuit]

MALLOY: Miami, Florida. It brings some immediate images to mind, often involving beaches, parties, and glamour. From the tourist packed Ocean Drive, the bustling streets of Brickell, to the music filled air of Calle Ocho in Little Havana. Even if you are on vacation, in Miami it seems like there is no time to relax.

[MUSIC: Afro Cuban All Stars, “Amor Verdadero” on A Toda Cuba Le Gusta, World Circuit]

MALLOY: Many looking for a bit of peace and quiet from the never-ending party that is South Beach head south towards the keys.

[DRIVING SOUNDS]

MALLOY: But, there is a sanctuary just an hour west of Miami. The vast and peaceful wilderness of Everglades National Park.

The Everglades National Park is only a portion of the natural ecological system that is the Everglades. (Photo: National Park Service, Wikimedia Commons CC)

[DRIVING SOUNDS]

MALLOY: As I drive west towards the national park the electricity of Miami dwindles and the skyscrapers fade away. The air softens as the sounds emerging from the open windows change from beeping horns to birds.

[BIRD SOUNDS]

MALLOY: There is a visitor center not too far into the park where I am going to meet my guide who will introduce me to many of the exciting species of the everglades.

KOMINOSKI: My name is John Kominoski and I'm an associate professor at Florida International University in Miami. I'm an ecosystem ecologist and I've been studying the Everglades for the past seven to eight years.

John Kominoski is an Associate Professor and ecosystem ecologist in the Department of Biological Sciences at Florida International University in Miami. His research focuses on organic matter processing at the interface of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems and is part of the Florida Coastal Everglades Long Term Ecological Research. (Photo: Lizz Malloy)

MALLOY: John sports an excited smile and long khaki pants, despite the 82-degree weather. He describes the Everglades as a mosaic of habitats and that nothing like it can be found anywhere else in North America. Soon we embark on a journey to one of John’s recommended trails. Dense carpets of grasses extend toward the sky on either side of the road.

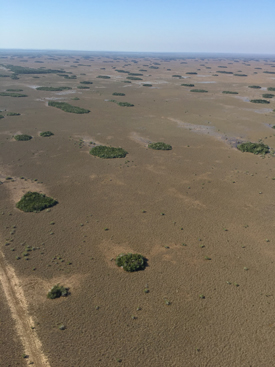

KOMINOSKI: It looks like a prairie. It doesn't look like a typical wetland that people are familiar with. When you're on the ground, you can't really see these open water habitats. And you would probably assume that the whole area was dry.

The Everglades is spotted with tear drop shaped tree islands. (Photo: John Kominoski)

MALLOY: From the mid 1800’s to the mid 1900’s there were constant efforts to develop the Everglades because it was seen as useless land. It wasn’t until Marjory Stoneman Douglas wrote The Everglades: River of Grass in 1947 that people began to recognize the Everglades as the rare ecological jewel that it is.

[BIRD AND WALKING SOUNDS]

KOMINOSKI: Okay! So, here we are at Royal Palm. Also known as Anhinga Trail and Gumbo Limbo Trail.

MALLOY: John heads through the trail entrance past massive banyan trees enveloped by strangler figs that look like they are made of dripping wax.

[WALKING SOUNDS]

KOMINOSKI: There's always water here because it's a canal essentially. So this is a great place for people to come to see alligators to see fish and hear fish, and birds and frogs and all that. So, we've got the double crested cormorant that's resting there on that dead branch. And we've got -- red, the red bark tree is gumbo limbo, as in the gumbo limbo trail. It's also called the tourists tree because it's red and peel-y [LAUGHS].

MALLOY: Along the other side of the trail is a sea of grasses that extends towards the sky, meshing greens, golds, and blues. Speckling the sawgrasses and invasive cattails are a variety of birds that don't seem to mind our company.

[BIRD SOUNDS]

The native Anhinga is not easily bothered by tourists in the park. (Photo: alans1948, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

MALLOY: A native diving bird called the anhinga suns its wings on a railing as a group of visitors look on and angle for photos. Unlike other water birds, such as ducks, anhingas don't have oil on their feathers to keep them dry when dive in the water for their prey. This helps them weigh their bodies down so they can dive deeper, but to dry off it takes a little bit of time and some sunbathing.

KOMINOSKI: Should we walk down to the end of the trail…?

MALLOY: Yeah!

MALLOY: This trail is full of excited visitors pointing and smiling at all the different wildlife that surrounds them.

KOMINOSKI: Okay, so here's our first alligator and whoa! Active!

MALLOY: An alligator, some 6 feet long, jumps in the canal about five feet in front of us behind the trail railing and scoops up a baby alligator in its mouth like a snack.

KOMINOSKI: So, this is definitely a female. And, it's possible that that jump that she made was to protect her baby. Wow. That is really special.

[ALLIGATOR CHIRPS]

The American Alligator is an abundant species in the Everglades. (Photo: Lizz Malloy)

KOMINOSKI: Yeah, she's definitely protecting that little one. Beautiful. This is kind of one of the beautiful, unique experiences you get when you're out in the Everglades.

MALLOY: Female alligators are protective mothers, who will sometimes keep their babies in their mouths to protect them from predators, like other alligators or even some birds. When they hear their babies making their distress call…

[ALLIGATOR CHIRPS]

MALLOY: ... the mother alligators go into full defense mode. But, I suppose that we aren't much of a threat because soon she lets her baby swim free from her jaws.

KOMINOSKI: This is the only place in the world where crocodiles and alligators coexist. And, fun fact, the American crocodile is very docile and actually more docile than the American alligator. So the American alligator is more territorial than the American crocodile, but the crocodile look scarier than the alligator to me.

MALLOY: I was inspired by John’s descriptions of the mangroves and megafauna that lie where the Everglades meets the ocean. So, I began my 30-minute drive south to the Flamingo visitor center. Grasslands became cyprus domes and cyprus domes became hardwood hammocks and hardwood hammocks eventually became mangroves as I reached my destination.

A scenic road connects Ernest Coe Visitor Center and Flamingo Visitor Center in the Everglades National Park. (Photo: John Kominoski)

MALLOY: I rent a kayak at the visitor center.

[WATER SOUNDS]

MALLOY: And paddle through the waters that are the lifeblood of the Everglades. Thrilled to be drifting past lumbering manatees and sun-bathing crocodiles. I feel like the star of my own nature documentary.

Where Everglades National Park meets the ocean, visitors can kayak through the mangroves. (Photo: Vincent Lammin, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

[WATER SOUNDS]

MALLOY: I can easily see why my guide John Kominoski loves this national park.

KOMINOSKI: You don't have to be a scientist to appreciate and want to protect the everglades. I think you just have to be somebody that wants to connect with yourself and with nature in a place that is experiencing a lot of change and may not be here for as much time as we hope it will be.

MALLOY: And change here means sea level rise, development, and climate change, which all threaten this delicate ecosystem. But, drifting along with the manatees, all that seems a million miles away.

[BIRD SOUNDS]

The Everglades National Park, although only half of its original size, covers 1.5 million acres. (Photo: John Kominoski)

MALLOY: For Living on Earth, I’m Lizz Malloy in the Everglades National Park.

[BIRD SOUNDS]

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth