How To Be A Good Creature

Air Date: Week of July 12, 2019

Sy Montgomery (left) poses here with her beloved Border Collie Thurber and friend and occasional writing partner Elizabeth Marshall Thomas at Sy’s New Hampshire farmhouse. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

From tarantulas in French Guinea to reclusive, aquarium-dwelling octopuses to the dogs and chickens in her own backyard, naturalist and author Sy Montgomery has connected with creatures all over the globe. They are her friends, her family, and especially her teachers. In her latest book, How To Be A Good Creature, she looks back on the valuable life lessons she’s learned from her friendships with feathered, furred and tentacled animals. Sy Montgomery joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss her treasured memories of these creatures.

Transcript

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Author and long-time friend of Living on Earth Sy Montgomery wrote the New York Times Best Selling memoir, How To Be A Good Creature. In it, Sy tells us exactly that. And who knows better than Sy how animals can teach us how to be good inhabitants of the world? From tarantulas in French Guinea, to reclusive aquarium-dwelling octopuses, to dogs and chickens in her own backyard, Sy has connected with creatures all over the globe. They are her friends, her family, and especially her teachers. Joining us now from her home in Hancock, New Hampshire, is author Sy Montgomery. Now, this book is a memoir that really talks about some 13 different creatures that have taught you how to be a good creature. And you start your stories with Molly, the dog.

MONTGOMERY: I'm looking at her picture right now on my desk. Yeah, Molly. Molly was essentially the older sister I never had. I mean, most little girls idolize their older sisters. I never had any siblings but I had something better. I had a Scottish terrier and even though she was chronologically younger than I was, I was very aware that dogs mature earlier than we do. They become adult in just a few years. We take, you know, 15, 18, 21 years to mature. But Molly was a fierce, strong, independent, wonderful, wise, adult individual. And I wanted to be just like her.

CURWOOD: Ah, your dog taught you to grow up to be a strong woman.

MONTGOMERY: Yes, she did. She totally did. And I used to dream of the day that I could run away with Molly, and live in a hollow tree or live in the woods somewhere, that with her, I'd be able to learn the secrets of the animals who lived in the wild. And that's what I went on to do.

After her initial visit with the citizen science group EarthWatch, Sy Montgomery returned to the Australian Outback where she studied a trio of emus, like those seen above for an extended period. (Photo: Greg Scales, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, in your book, you recount your career, and it seems like you're well on your way to being the journalist, a little girl had a newspaper, and grown-up woman has job as a reporter, and you're all set to go, and then, well, something happens along the way.

MONTGOMERY: Well, my father, ever my champion, gave me the gift of a trip to Australia, and I didn't want to just go as a tourist. I wondered if there was some way that I could volunteer or do a study or, you know, help a scientist. And there was. There's an organization, as you know well, called Earth Watch. You can spend a couple of weeks helping a scientist almost anywhere in the world. So, I looked to see what they had in Australia. And what they had in Australia was a project called “drought refugia.” And this was a study with Dr. Pamela Parker of the Southern Hairy-Nosed Wombat. Now, who can resist that? Almost nothing was really known about them until Dr. Parker came along. So, for a couple of weeks we lived in tents in the Outback and by day we would try to find the wombats. And I was crazy about this. I had the best time and I worked really hard, and afterwards, Dr. Parker was impressed enough to say, Sy, I wish I could hire you to work for me. I wish I could buy you a ticket to come back and Australia, but I can't. But what I can do is, if you ever wanted to come back on your own, I'd let you stay at my camp and you could eat my food. So, I went back to my wonderful job. And I quit that job and moved to a tent in the Outback. And I studied emus.

CURWOOD: And, you write that the emus really taught you something important, what was that?

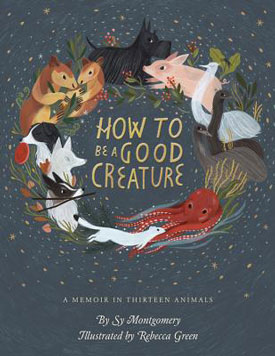

Sy Montgomery’s book, How To Be A Good Creature: A Memoir in Thirteen Animals, is a New York Times Best Seller. (Photo: The Toadstool Bookshop)

MONTGOMERY: They showed me a lot. I mean, I certainly learned a lot of field work knowledge from them, but the most important thing, Steve, it was that doing the science, doing the reading, all that intellectual stuff really matters. But, if you want to understand an animal, you also have to bring to that understanding your heart. I let them choose to be around me, and I wouldn't approach them so closely that they would feel frightened. The minute that they seemed upset I’d just back off and stay still. You know, at first I thought, I'm gathering important scientific data. This is really fun. And the data is important and taking notes is important. But the more I follow, the more I was with them. I found myself falling in love with them. And there were times that I realized that taking the notes wasn't the most important thing I was doing. Maybe the most important thing I was doing was falling in love.

CURWOOD: Indeed. Now, you're a writer, and so, there's always the editing process. Just how difficult was it for you to whittle your stories down to just 13 animals in 10 chapters?

MONTGOMERY: Well, I did leave out some important animals in my life, and they very much still animate my life. But the ones that I included in this memoir, it's a memoir in 13 animals, that’s the subtitle, are ones that taught me very specific lessons for my life about how I should perceive the world and how I should behave. And I chose those that best illustrated that. Some of the animals taught me how to cope with loss. Some animals taught me how to find your destiny. One animal showed me how to forgive, and Thurber showed me that there's always something wonderful lurking right around the corner that you can't possibly anticipate.

One of the lessons conveyed in Sy’s book was that of forgiveness, inspired by her forgiveness of an ermine that had killed one of the chickens she kept. (Photo: Fiona Paton, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Talk to me about how a creature taught you to forgive.

MONTGOMERY: Well, this was an ermine. They are the white-coated version of weasels, who live in the north. So, this weasel, ermine, who I met, I met on Christmas morning. And every Christmas morning I always make my hens a big bowl of delicious hot popcorn. And I was carrying it down to give to the ladies. And one of my girls was lying dead on the floor of the coop. And someone had a hold of her head. And when I pulled her away, this white head popped out from the corner with coal black eyes. It was a tiny little critter. This animal probably weighed less than a handful of coins, but so fierce, and I could not be mad at that weasel. I mean, the animal had just killed someone who I loved and it was Christmas morning and you’d think that would make you really angry or that you might even hate someone who did that. But that wasn't what I experienced at all. What I experienced was the glory of this creature, the glory of its wildness, and its ferocity, and its determination, and its courage, its braveness. And I thought about my mother. And my mother had just died, oh gosh, that very year. But throughout my childhood and growing up and even as an adult, we'd had a number of disagreements and, at one point, my parents had disowned me for marrying the love of my life, Howard Mansfield. We had a lot of disagreements, but in the moment that I beheld that ermine, I just felt this wave of forgiveness sweep over me for my mother. And I realized that she was fierce like that weasel, she shared a lot of the characteristics of that ermine, and there was so much in her to admire, and I realized how much I loved her, and how much I missed her.

CURWOOD: Now, you write about octopuses, in fact, a little shout out about us at the show when we went to meet one of your octopus friends at the New England Aquarium. How did you get into, well, talking and being with octopuses?

MONTGOMERY: The first octopus I met, I went in with an assignment for Orion Magazine on the intelligence of octopuses. And one of the keepers opened up the tank where Athena lived. And this huge animal, I mean, her arm span had to have been, oh, gosh, nine, ten, or more feet. She turned bright red with emotion. She slid from her lair, looking me straight in the eye with hers, and then out from the cold, 47 degree water come boiling up her arms, reaching for me with these questing suckers. So, naturally, I plunged my hands and arms right into the water to greet her. And the next thing I knew, I was patting her head. And she was just as curious about me as I was about her. And I came back several times to meet her. But the thing about octopuses is, they just don't live very long. And after only a few visits, I got the horrible news that she just died of old age. So, the next octopus who came, they invited me back to meet her, and that's the octopus, who you met, Steve, Octavia. And there's a chapter in this book about Octavia. And when I introduced you to Octavia, only once before had we had a close interaction. So, I really wasn't sure what she was going to do when she met you. But she was quite brilliant. She was interacting with you, and the producer, and the sound person. And while we were all petting, and feeding, and watching this octopus, just our senses being flooded with the sensation of touching this beautiful animal, feeling her suckers watching her change color right out from under our noses, she stole a bucket of fish, do you remember that?

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] I do.

MONTGOMERY: [LAUGHS] She totally outwitted us.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] You know, I have to confess I was a bit fearful. I mean, I hadn't met an octopus before.

MONTGOMERY: Right. And they're depicted as monsters in all kinds of literature, and paintings, and etchings.

CURWOOD: Yeah, when I reached in their first there was one sucker, and then there were several suckers, and everything attached. But thanks for you being there, I simply relaxed. But when I heard that she too died of old age and motherhood, I was sad.

Octavia rises out of her tank to greet Sy. (Photo: Living On Earth)

MONTGOMERY: I know, I know, they just break your heart. But I knew her more intimately than any other octopus, because I knew her pretty much from when she first showed up at the aquarium until she died. And it was just so beautiful to be able to see the full arc of her life. And the last thing a mother octopus does is tend for their eggs. And even though her eggs were infertile, she tended them with all the tenderness and love that a mother octopus would feel for living eggs. And that was a real blessing to be able to see.

CURWOOD: Now you, I think you struggle at times with making sure to not anthropomorphize the animals in your stories. But you also make the point that, perhaps the worse mistake is to assume that animals are emotionless, that they don't have emotions.

MONTGOMERY: Exactly, exactly. What we don't want to do is project our feelings onto other animals, or other people. And so, and, we can't help it sometimes, you know, we can easily imagine that an animal wants to be petted, and when maybe it doesn't. That's a common mistake. But more dangerous, as you said, is to think that they don't have thoughts or feelings, thoughts and feelings are not human things alone. We're part of a huge family of living creatures, and consciousness does not belong to us alone. Emotion does not belong to us alone. These are things that are helpful to animals to let them live. So, we do ourselves and the creatures a terrible disservice to assume that they are thinking nothing, that they are feeling nothing, that they know nothing, that they do not make decisions. We will never understand the lives around us unless we realize that animals are thinking, feeling, knowing beings.

CURWOOD: So before you go, Sy, what do you hope to impart to animal loving listeners, or even those whose relationships with animals may be a little more tenuous or even skeptical?

MONTGOMERY: Well, I would want to say that we are embedded in this glorious world of other souls, other minds, and these others have so much to teach us. And being surrounded by teachers in a confusing and difficult world should make us feel far more at home here, and far more in love with our homes, and give us the courage to fight for this beautiful Earth that is so imperiled, and so alive.

Host Steve Curwood and Sy in 2011, on a visit to Octavia the Octopus at the New England Aquarium. (Photo: Living On Earth)

CURWOOD: Sy Montgomery's book is called How to Be a Good Creature: A Memoir In 13 Animals. Sy, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

MONTGOMERY: Oh, such a pleasure, Steve.

BASCOMB: So, Steve, did Sy convince you animals are conscious and aware?

CURWOOD: Well, my dog Jilly already has. I have to spell the word food, because if I say it, she heads for her bowl and gives me the look.

BASCOMB: Yeah, I know that look.

CURWOOD: And by the way, if anyone would like to hear Sy Montgomery speak about being a good creature, and you’re in the Boston area on July 18th you can catch her that evening at the New England Aquarium. For more information, find this story on the Living on Earth website, LOE.org

Links

Learn about Sy’s July 18, 2019 lecture at the New England Aquarium here

How to Be a Good Creature: A Memoir in Thirteen Animals

Our interview with Sy Montgomery and Elizabeth Marshall Thomas from 2017

A Previous LOE story where we met Octavia, the Giant Pacific Octopus

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth