Exploring the Parks: Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve

Air Date: Week of August 2, 2019

Aniakchak’s renowned caldera is a beautiful reminder of Alaska’s location within the Ring of Fire. (Photo: Courtesy Chris Solomon)

Deep within the remote wilderness of the Alaska Peninsula, Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve is one of the least-traveled places within the national park system. Designated by President Jimmy Carter as a national monument and preserve in 1978, Aniakchak is always open to visitors with no amenities, no cell service, and no park rangers -- hence its slogan, “No lines, no waiting!” Chris Solomon, who wrote about Aniakchak for Outside magazine, joined Host Steve Curwood to talk about his experience among the grizzly bears and volcanism in this wild and remote patch of public land.

Transcript

Summer is a time of travel in the Northern hemisphere, and you have probably already had plans. But if you don’t or are thinking ahead to next year, we’ll be bringing you some stories in the weeks ahead that explore the vacation possibilities in US public lands.

[MUSIC: Sharon Jones & the Dap-Kings, "This Land is Your Land" on Naturally, Daptone Recording Co.]

CURWOOD: Today we look more than 5000 miles north to Alaska, and the Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve. This spot on the Alaska peninsula it is one of the least visited of our public lands and touts the catchphrase, “No lines, no waiting”. And it’s for the most adventurous among us as there are no roads to access the preserve. You must arrive by plane or by foot and don’t think about going in winter. But Outside Magazine contributing writer, Chris Solomon, says that’s all part of the charm. Chris, welcome to Living on Earth!

SOLOMON: Oh, thanks for having me, Steve.

CURWOOD: What made you decide to go to one of the least visited places in the national park system?

SOLOMON: I really like to go as far off the map as possible. I mean, I've joked that my cell phone is a, is a bit like a reverse Geiger counter. As the cell phone bars of coverage drop, the possibility of adventure and a good time seems to increase. Everybody talks about the most popular national parks, and those places are great. But I wondered, what's the least popular place? And I wondered, is there something interesting about that place? Or maybe, why is it so unpopular? There was a list on the National Park Service website of the places that got the fewest visitors. And year after year, Aniakchak anchors the bottom of the list or is very close to the bottom.

CURWOOD: So, remind me, where in Alaska is Aniakchak actually located?

Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve resides on Alaska’s peninsula, which leads into the Aleutian Islands. (Photo: Courtesy of Chris Solomon)

SOLOMON: It's 350 to 450 miles, I forget exactly, southwest of Anchorage on this stub of a peninsula called the Alaska Peninsula that's warted with these quiescent volcanoes. It's where Katmai National Park is that people have probably heard of. Lake Clark National Park is in the area, these better known national parks. And then after the peninsula runs out, the Aleutian chain begins with people are probably more familiar with at least from a map. But, Aniakchak is on that peninsula as well. But, it's so little known that even as we sat in the airport, there was a big mural on the wall and these other national parks were on there and Aniakchak wasn't even on the mural in the airport as we headed there.

CURWOOD: What kind of company did you have with you, both two-legged and four-legged?

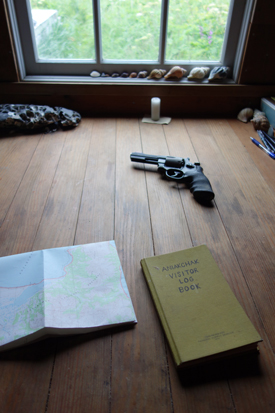

SOLOMON: [LAUGHS] Yeah, so it was just three of us. There was a great photographer named Gabe Rogel, who's now a good friend. And our guide was Dan Oberlats who is the founder and chief guide of Alaska Alpine Adventures. So, it was just us three, along with a 44 Magnum called Pepe that was Dan's, to try and keep the bears at bay, because the Alaska Peninsula is, is known for some of the heaviest concentrations of the largest brown bears on Earth. They're relatives of the Kodiak brown bears, which are often said to be the largest bears, but the Alaska Peninsula bears are basically the same bears. One census found 400 brown bears per 600 miles, which is just astounding. I mean, there's something like 700 bears in 60,000 square miles of the Yellowstone ecosystem.

Chris’s guide carried a gun named Pepe to defend against grizzly bears. (Photo: Courtesy of Chris Solomon)

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Oh, my! So there you are, you head to Alaska, to Aniakchak, but I guess you just don't rent a car in Anchorage or something and start driving.

SOLOMON: No, you don't. So, you have to fly to for instance, King Salmon, which is one of the bases of the Bristol Bay Salmon Fleet, and then maybe try to get to Port Heiden, which is a little dot of a town. And then, from there, you could either potentially fly a float plane into the monument, or in our case, the weather's so bad and unpredictable that we just decided to hoof it from Port Heiden. And we hiked about 22 miles up into the centerpiece of Aniakchak, which is this spectacular caldera.

CURWOOD: What exactly is the caldera?

SOLOMON: Yeah, so a caldera is essentially a volcano that has blown up, and then collapsed on itself and leaves a big bathtub. Essentially an empty ring, maybe the one readers would know best is Crater Lake in Oregon. And so Aniakchak has this great history and, it was so fun to discover this stuff, Steve. About 7000 years ago, as the Egyptians were kind of doing their thing and really dominating the Mediterranean area, this several thousand foot volcano, Aniakchak would have been, blew its top with the force of something like 10,000 atomic bombs. And then it, having done that, it collapsed upon itself. And over the course of a couple thousand years, it filled with several thousand feet of water. So it was this bathtub, and then one of the sides burst out with this tremendous flood. So then it became this empty ring with a hole in one side. And one of the great discoveries of doing this story is, you know, the native peoples, of course, knew about this place. But then in the early 20th century, this incredibly charismatic guy named Father Joseph Hubbard, who was called the “glacier priest”, came and quote-unquote, rediscovered it. And the glacier priest was this swashbuckling Jesuit from Santa Clara University, he would go on these expeditions around, around Alaska, often with a bunch of football players from Santa Clara University with their leather helmets on and they went to Aniakchak and they explored it. And they had found this place that hadn't blown up again in a couple thousand years. And inside were all these orchids growing in the warm soil, and they had bunnies that hadn't seen man. And so they would just walk right up to the football players who, who then ate them for dinner. And he described this sort of paradise found. And he wrote about this for, you know, places like National Geographic, and then he went away, and that year, it blew up again, and he came back and he described this kind of Dantean Inferno, and the place almost killed them with all the sulphurous gases. And so he wrote about it again, and became even more famous. So the glacier priest was one of the great finds of this story, and I was able to kind of follow some of his tales and writings as we explored the place.

At the bottom of Aniakchak’s caldera is Surprise Lake. (Photo: Courtesy of Chris Solomon)

CURWOOD: So take me back to a memorable moment or two for you in Aniakchak National Monument.

SOLOMON: We drop into the caldera after just being completely in the mist, you know, not knowing what we're going to find. And we drop into the caldera the second day, and we see this amazing place, and we camp by this beautiful little lake that's still the remnant of the bathtub that had been filled. And it's this lake called Surprise Lake where salmon still swim up into it and spawn, and they apparently taste like minerals from all the volcanic stuff that's still in the lake. And the next day we crawl out and we get on to the rim and you can look down and there are these pumpkin-colored hot springs that still push up out of the floor of the volcano. And it's just some of the most dramatic colors I've ever seen. And so you have this, you have this Surprise Lake that's the blue of you know of like a gemstone and right next to it you have this yellow and red hot spring pouring into it and it's just -- I still have the, the picture as my screensaver on my computer because I never tire of it.

CURWOOD: Is there another memory you have from there that you would like to share that’s sort of incredible?

Orange lava flows and hot springs speckle the bottom of the caldera, bleeding into Surprise Lake. (Photo: Courtesy of Chris Solomon)

SOLOMON: You know, one of the -- [LAUGHS] this might not be the kind of experience everyone wants, but we rounded a curve in a bay as we were exiting the monument. And around the corner, maybe a couple hundred yards away, was a, was a brown bear who was snuffling around, maybe he was on a kill, we couldn't tell. And he headed up on to the bluff where there was a lot of alders and underbrush and we couldn't see him anymore. That's not great because you want to keep an eye on the bear. So we decided to cut the corner across the bay and just walk through the tide flat and keep our distance. So we took off our shoes and started walking across the tide flat and the tide flat turned out to be almost thigh deep with tidal mud. So now we're reduced to walking at about one step every four or five seconds, as the mud is just sucking at our bodies. Meanwhile, we can hear the bear 150 yards away chuffing, you know, making unhappy noises in the underbrush. And then we get to the other side of the, of the bay. And the guide encourages us to walk as fast as possible. And I notice that he has drawn Pepe, the 44 Magnum, which encourages you to walk even faster. And we get to the other side of the brush. And we have no idea where the bear is. And there's a small path through the woods that we have to take. There's no alternative. And it turns out that it's what's called a bear trail. And these bear trails are these habitual paths that bears use for years, sometimes a century, sometimes longer. They're just, they're bear highways. And it was so well used by bears, by these thousand-pound bears, that the bear trail was knee deep with use. It was so worn. So we're walking through this incredibly dense thicket. We can't see 10 feet in front of us, with gun drawn, screaming and yelling 'hey bear!' 'Hey, bear!' with no idea where the bear is. And then we pop out on the other side safe. And we inflate our little rafts, and we float across a bay. And there's whales diving and puffins flying, and it was just a great end after a lot of adrenaline. So, [LAUGHS] It's the kind of thing that, you know, makes the colors a little brighter in life.

CURWOOD: How worth it was it to go?

Brown bears are highly abundant within Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve. (Photo: Courtesy of Chris Solomon)

SOLOMON: For someone like me who values wilderness, and solitude, and adventure, and who is willing to endure a little bit of discomfort and sogginess and freeze dried food [LAUGHS] for that payoff. It was a memory of a lifetime. And if you too are of that bent, I would encourage it highly. In 10 days, we saw two other people and they were fishermen who had simply pulled up on shore to just poke around for a few minutes. Otherwise we saw, we saw more bears than people; we saw beauty that I still tell people about. I made some friends for the rest of my life. I do find, and as I've written elsewhere, that the few people you go out with on these kind of experiences, these kind of wilderness experiences, have a way of really sharpening the relationships among the people that one spends time with. In short, it was one of better experiences of my life.

CURWOOD: Chris Solomon is a contributing writer for The New York Times and Outside Magazine. Chris, thanks so much for joining us today.

SOLOMON: Oh, it's my pleasure. Thank you.

CURWOOD: And, I'm glad the bears didn't get ya.

SOLOMON: [LAUGHS] So am I!

Chris Solomon is the Society of American Travel Writers 2018 Travel Writer of the Year. (Photo: Courtesy of Chris Solomon)

Links

Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve

Outside | “Baked Alaska: Surviving Aniakchak National Monument”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth