The Best Science and Nature Writing

Air Date: Week of January 3, 2020

Emi (mother, foreground) and Suci (baby, background), two of the Sumatran rhinos at the Cincinnati Zoo in 2006. (Photo: MrsApplegate, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The best science writing strives to entertain and educate in equal measures, and to help make the jargon of the scientific world accessible to the general public. To cover some of the most captivating recent science writing Living on Earth's Aynsley O'Neill spoke with Sy Montgomery, a bestselling author and the guest editor for the 2019 edition of The Best American Science and Nature Writing.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

It takes special talent to write about science for the general public. Part of the challenge is translating the technical jargon of science into more accessible language. And trying to explain anything new is also hard, especially since it can come with complexity and uncertainty. Unless you are Sy Montgomery. She’s one of those science writers who makes you feel less like she is teaching you something and more like she’s sharing some exciting thing she’s discovered. Sy is a New York Times best-selling author and National Book award finalist who has written over 20 books about the natural world. Most recently she was the guest editor of the 2019 edition of The Best American Science and Nature Writing. Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill caught up with Sy to discuss some of the best science and nature stories to come out of the last couple of years.

MONTGOMERY: Boy, there was a lot of good science journalism happening, which is kind of a miracle when you consider that science writing, in newspapers at least, there's just no space for it anymore. So, it's kind of a minor miracle that these kinds of stories, some of them, you know, investigative journalism that takes weeks, months to complete, is actually coming out. But it was hard deciding which were the best ones to include. And I was delighted that it was so difficult to make that choice.

O'NEILL: Let's start talking about some of these incredible, incredible pieces. A personal favorite of mine and a personal favorite of yours, if I remember correctly, has to do with Sumatran Rhinos, if you could tell us a little bit of that story.

MONTGOMERY: Well, who doesn't love a good Sumatran Rhino story? Sumatran Rhinos are the rarest of the rhinos, and rhinos are disappearing so rapidly from the earth. Of all the species, the Sumatran, the only one who's a hairy rhino, they have been under horrendous poaching pressure, and they're practically extinct in the wild. So, this is a fabulous success story called The Great Rhino U-Turn and it was written by Jeremy Hance for Mongabay. And it tells the story of how the species was rescued from extinction against all odds, thanks largely to Cincinnati Zoo. And the story goes like this. In 1995, there were only three Sumatran Rhinos in America in zoos, and they were the only ones remaining from 40 rhinos that had been captured in the wild to breed since 1984. 11 years after these 40 rhinos were captured, half of them had died. None of them had bred. So, by 1995, three were left. One was in New York. One was in Cincinnati. One was in California. So you're not gonna get a lot of breeding done that way. So, it was decided to bring the two female rhinos to Cincinnati. First, they had to find out, are the females even in condition to breed? So they trained the females to submit to ultrasounds, so you could look inside them and see how they were doing. They found out that one had a horrible growth in her uterus. She was never going to have a baby. They were down to one female and one male. And the female was named Emi and she wasn't ovulating. So, what are you going to do about that? Well, they took a big risk. They figured, you know, let's just put the two of them together. Now, why is this big risk? One ton rhinoceros meets another one ton rhinoceros. And what if they feel like I wouldn't mate with you if you were the last rhino in the world? Wait, you are the last rhino in the world! But I still don't want to mate with you. If they get into a fight, you have got two tons of big problems. And typically, they're very solitary animals, and they don't want to be together until the female is ovulating. They put two together. And sure enough, the male did in fact mount the female. Well, no baby resulted from that. She did have four pregnancies, but all those pregnancies were not successful. Then a fifth, and then the sixth one. You wait 16 months for a baby rhino. The infant is born. And his name was Andalas. And he was healthy. And she gave birth to two more. And the wonderful thing is they're no longer at Cincinnati Zoo. Everybody misses them. But where are they? They're in Sumatra, at a breeding center and perpetuating their race. And this was just against all odds, and just a wonderful story. And it shows you the individuality of the animals. I love the story because you got to kind of know the names of the animals and what their temperaments were like, and you got to know the big risk that people were taking. And when we take a risk to save a species, and it works, in this world in which sometimes you just want to take a cyanide pill, because it seems like everything is falling to pieces a story like this just warms your heart, and makes you realize, science is our way out of the mess we've created. And thank God, it's one of those inspiring, feel good stories, and it's one of my favorites in the whole book.

Black women are approximately four times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes as white women. (Photo: NICHD, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

O'NEILL: And now another one of the stories is again, to do with babies, but this time looking at humans and specifically, black women in the United States, what it is like for them. Could you share with us a little bit of that story?

MONTGOMERY: Yeah, wow, this blew me away. I couldn't believe it. It was one of those stories that you're reading it and just like oh my gosh, you can't believe it. The statistics blew me away. Started with statistics from 1850. Okay, slavery did not end until 1865. The white infant mortality rate was 217 per 1000 babies, the black infant mortality rate was worse, but not all that much worse, 340 per 1000, because babies just died all over the place. But then, between 1950 and the 1990s, babies of all races who died in the first year of life dropped 90%. Yay, this is awesome. In 1960, the US was ranked 12th in developed countries for infant mortality. But now, our country, the most developed arguably in the world, the richest country in the world is ranked 32 out of 35 and the US is one of only 13 countries in the world where maternal mortality got worse in the past 25 years. And what is driving that is the terrible death rate of black women and their babies. I was absolutely floored. Black infants in America are more than twice as likely to die as white infants. But what's even more shocking is that black women are three to four times more likely to die from pregnancy related causes than white women. And you're like, why? Well, immediately you think income disparity, you know, poverty. These women, maybe they just don't have the education. They don't know something's wrong, they don't have enough money to get to the doctor. People have all kinds of problems related to poverty. And that's not even it. And that's what blew me away more than anything else. It's not related to income. It's not related to education. A black woman with an advanced degree is more likely to lose her baby than a white woman with an eighth grade education.

O'NEILL: That statistic floored me when I heard that the first time. It's just shocking to hear that.

MONTGOMERY: Well, this is why journalism like this is what we desperately need. Everybody would have decided, oh, it's poverty or oh, it's education. But no, it's not. So, people went to work trying to find out what was the deal here. So, there were all kinds of other things they investigated. Were black women drinking or smoking more? Of course, let's blame the woman, right? It turns out, they drink and smoke less during pregnancy than white women. So that wasn't it. But something about growing up black in America was doing it. Then they looked at other statistics about what happens to sick black people in our medical system in general. And I was absolutely shocked. Diabetic black people are more likely to have a foot or leg amputated than diabetic white people. What's that about? Black people are less likely to get adequate pain relief in the hospital than white people. What is going on here? They receive inadequate treatment because they're black. So, this whole story that starts out horrifying, just gets more horrific with each page. But that's how you change things. And Linda Villarosa is part of the change because she, in this article, has pointed out what is going wrong.

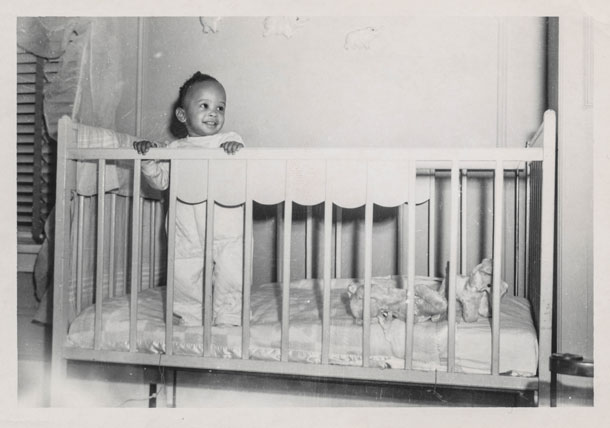

A young Black child in 1953. Infant mortality rates in the United States have gotten worse in the past few decades, due in large part to the high mortality rate of Black mothers and children. (Photo: SimpleInsomnia, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

O'NEILL: One of the things that really is incredible about that is how that author, she pulls together all of these statistics and this data, and she also combines it with this beautiful piece of storytelling about this one woman whose pregnancies she follows.

MONTGOMERY: It made, it made it very visceral and very real.

O'NEILL: One of the things that they mention in the article is how much racist mindsets can factor into how black women and black people in general receive treatment in hospitals.

MONTGOMERY: Yeah, that blew me away. There was one survey of doctors, and this, this is modern, this isn't like in the 1800s or anything, in which doctors said that they thought that black people were less sensitive to pain than white people. That's insane. That is crazy. And it makes me scared for all my black friends. And we never talk about stuff like that because my friends and I we talk about animals no matter what, but it scares me to death and you want to do something, but of course, you know, not even the doctors, if they have a bias you don't know you have a bias until someone points it out. So, thanks to this fantastic piece of investigative journalism, now we can make a change.

O'NEILL: A lot of the stories in this collection are stories of adventure, taking you everywhere from the deserts of Chile, to the Sea of Cortez to Cincinnati for those Sumatran rhinos, really examining what kind of science and what kind of scientific journalism can happen in these incredible places around the world. And one of the stories concerns a search for extraterrestrial life, but a search for extraterrestrial life on the planet Earth. Could you tell me a little bit about that story?

The Atacama Desert in Chile is home to a team of scientists’ quest to learn what extraterrestrial life might be like. (Photo: Alessandro Caproni, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

MONTGOMERY: Yeah, this was one of my favorites, too. In it, Rebecca Boyle takes us to the driest nonpolar desert on Earth. The Atacama Desert in Chile. So this is this totally alien spot on our own planet and she takes us there and why? Because it is the most like Mars of any surface on Earth. It's 90 degrees, if there was any shade -- there isn't -- with daytime gales; nighttime is perfectly still and from a distance, the place she went called the Salar Grande looks like this sea of pebbles. But you get up close and it resolves into a field of fissures and slabs called polygons and edged with these smooth round nodules, which are pure salt. Totally seems like another planet, but it's our planet. So this was once a salt flat. It dried up between two and 5 million years ago. The salt flat is at least 225 feet thick. And she gets to go to this utterly lifeless was looking place to look for life. And she finds it.

O'NEILL: It's incredible when you think about all these tiny microscopic critters that can exist, wherever you could possibly think of them on the highest mountains, in the depths of the ocean floor, in volcanoes and see events, all sorts of extremophiles who just cherish the most difficult place to live and they're still going to eke out an existence one way or another.

MONTGOMERY: It's amazing. And, like, Where is the life? Well, it's inside the salt nodules. She cracks them open with the scientists that she's accompanying. And inside, some of them are these little green stripes. And they're called halobacteria. And they are, they are alive! Life just loves to be anywhere, life seems so irrepressible. And for those of us who hope there is life elsewhere in the universe, this is thrilling. And it's this fabulous living laboratory. But what I love so much about what Rebecca Boyle does in this is she takes us to this place, we meet these cool people. And so she blends this adventure story with all the science. And she also quotes these wonderful Chilean poets. I mean, didn't you love that? I love that. There's some Raul Sarita and Gabrielle Mistral. And he would refer to the sun as Lord burn all things. And one of the quotes that she takes from this Chilean poet is one that I kind of feel like is emblematic for this whole, this whole book of fabulous science writing, and it's his exhortation, “lift up your face, child, and receive all things.” That's what science does for us.

O'NEILL: Wow, a stunning work of journalism. You're very right that that is very emblematic of all of these stories that you've put together. And I suppose now I have to ask, Who did you hope would read these stories and what do you hope people will take from them?

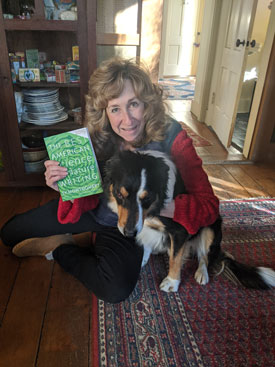

Sy Montgomery poses with The Best American Science and Nature Writing 2019 and her dog, Thurber. (Photo: Isaac Merson)

MONTGOMERY: Well, the lovely thing about every one of these stories is that I think anybody who likes to read anything, will enjoy them. Because they have such a fabulous wow factor. You know, you don't have to have any special training in science to enjoy these. And that's what great science writing does. It connects people with science and makes them care about and love science. What we do is bring to light the truths that we're finding in the world. We people have to have that knowledge, we have to have the truth in our hands, because our leaders aren't doing it for us. So we've got to take the lead. And we've got to make the change in leadership as well. In the introduction, I wrote about the Boston March for Science and I spoke at the kids’ March for Science, because as we've seen, children are not just the leaders of tomorrow, they are the leaders of today. And little kids were my audience. And I told them the story of a scientist that I'd worked with and went to Papua New Guinea with her. Her name was Dr. Lisa de Becque. And we climbed to 10,000 feet into this cloud forest. We're looking for tree kangaroos. We got radio collars on them, we got to find out where they went. We're in this cool place, I mean, cloaked with mist and burns and moss and these amazing animals that looked like Dr. Seuss had designed them. And all these kids were standing in the rain on this pouring freezing cold day, absolutely riveted to the story of Dr. Lisa de Becque and the science that she was doing good science writing is going to spark that interest in you. Whether you love science, whether you're 10 years old, whether you're ninety years old, it makes us excited about learning the truth of our world and makes us excited about the adventure of learning and the excitement of discovery. And that is part of what makes us human.

CURWOOD: Author Sy Montgomery speaking with Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill.

Links

Listen to our most recent book interview with Sy Montgomery, for How To Be A Good Creature

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth