Supreme Court Clean Water Win

Air Date: Week of May 1, 2020

Degraded coral reefs at Kahekili Beach Park, west Maui, Hawai‘i. A 2018 USGS study found little evidence of live coral near groundwater seeps. (Photo: Peter Swarzenski, USGS. Public domain)

In a key decision for environmental law, the US Supreme Court has handed down new guidance on when indirect sources of water pollution require a Clean Water Act permit. Vermont Law School Professor Pat Parenteau joins Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss how the 6 to 3 decision came about, and precedent for environmental law.

Transcript

BASCOMB: The Clean Water Act is designed to protect lakes, rivers, and the ocean from pollution, and the law states any direct discharge into those waters requires a federal permit. But when sewage from a municipality in Hawaii that was being pumped into the ground started leaking out into the ocean officials said no permit was needed as it was not a direct discharge. And though this view was championed by the Trump Administration the US Supreme Court recently ruled 6 to 3 that on a functional basis the treated sewage was being dumped in the ocean in violation of the law. The ruling could set a key precedent for years and here to explain is Vermont Law School, Professor Pat Parenteau. Pat was part of a group of law professors that filed an amicus, or “friend of the court”, brief in the case. Hey Pat, welcome back to Living on Earth!

PARENTEAU: Thank you, Bobby, good to be with you.

BASCOMB: So Pat, tell me about the Clean Water Act case in the County of Maui vs. Hawaii Wildlife Fund. What was the Court asked to decide here? And what did they decide?

The Supreme Court of the United States is conducting its business remotely during the COVID-19 pandemic and will hear oral arguments by phone this May. (Photo: Phil Roeder, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

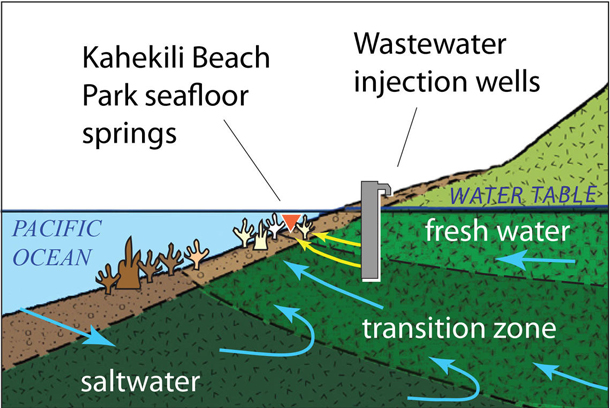

PARENTEAU: Yes, it was a very important Clean Water Act case. And the question was, what do you do when you have an injection well, that is injecting treated sewage into the groundwater, which then flows into the ocean and causes all kinds of problems. This particular discharge in Maui was impacting a very important coral reef and the reef was deteriorating. This is also a very popular surfing beach and swimming beach. And of course, treated sewage still has a certain amount of bacteria. So there was that question as well. The legal question was if you discharge through the groundwater into the ocean, is that the kind of activity that requires a permit under the Clean Water Act? The County of Maui said it didn't; the State of Hawaii didn't require a permit. And this activity has gone on for many years. And finally, a lawsuit was brought, what we call a citizen suit, by a group of conservationists in Hawaii. And they convinced the courts that even though it was an indirect discharge to the ocean, it was still one that required a permit. And so this issue had to go all the way to the United States Supreme Court, because we've had other circuit courts who ruled in the opposite way, saying that it must be a direct discharge to surface water in order to require a permit. So that was the question the Supreme Court had to resolve.

The Roberts Court, from November 30, 2018. Seated, from left to right: Justices Stephen G. Breyer and Clarence Thomas, Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr., and Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Samuel A. Alito. Standing, from left to right: Justices Neil M. Gorsuch, Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, and Brett M. Kavanaugh. (Photo: Fred Schilling, Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States)

BASCOMB: And what did they decide in this case?

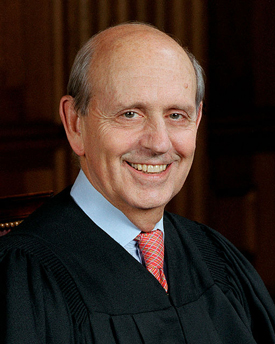

PARENTEAU: Well, what they decided was to kind of split the baby. The environmental groups were arguing that anytime that you could trace a discharge into groundwater that ended up in surface water, that should require a permit. And the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals agreed with that and called it the "fairly traceable" test. The petitioners, the County of Maui joined by EPA and the Trump administration, argued, no; no indirect discharge should require a permit, it would have to be a pipe that you know, discharged directly into the ocean in order to require a permit. The Supreme Court came down in the middle and said, We don't agree with the Ninth Circuit in this broad test of "fairly traceable". But we also don't agree with the County and with the Trump administration that only direct discharges should be regulated. And Justice Breyer wrote an opinion, and he came up with a new test. He called it the "functional equivalent" test, and what he meant was, if the discharge through groundwater is the functional equivalent of direct discharge to the ocean, that's going to require a permit. And what he expressed was a concern that if you didn't capture some of these indirect discharges, that would create a big loophole in the law, and it would allow people to get around having to get a permit by simply moving their pipe back from the river or the lake or injecting waste into the groundwater, even though they knew it was going to go right into the surface water.

A USGS diagram showing how injected wastewater from the Maui facility travels to seafloor springs among a nearby coral reef. (Photo: USGS, Public domain)

So Justice Breyer wrote the opinion; the key here was Chief Justice Roberts joined the opinion, and even more surprisingly, Justice Kavanaugh join the opinion. So this is really the first time that Justice Kavanaugh has sided with the more liberal wing of the Court in a decision that really gave at least a partial victory, I think, to the environmental groups.

BASCOMB: Now, what are some other examples of indirect water pollution situations that could be impacted by this decision?

PARENTEAU: There are quite a few. There are a lot of these injection wells that sewage treatment plants use to get rid of their, their treated effluent rather than discharge them directly to the river. So there's quite a few of those around the country. Another big category is these coal ash pits all through coal country in the Southeast part of the United States, the Midwest. There's a legacy now of all this coal that we've mined and burned in power plants. And the residue of that is this toxic ash material, which is just dumped, really, in many places, in these open pits that don't have liners. And what we're finding now is that all of this coal ash is leaching into the groundwater into the rivers. And so the question there is that when this coal ash pits leach these heavy metals down through the groundwater that is getting into the surface water, is that another form of indirect discharge requiring a permit? The courts on this question have been split, and so now we have this new test that the Supreme Court and the Maui case has come up with. And some of these cases are probably going to have to be reviewed under this new test to see whether or not some of these indirect discharges actually require a permit. So this, this case will take several years, I think, to sort out what this new test is going to look like.

Associate Justice Stephen Breyer’s opinion for the County of Maui v. Hawaii Wildlife Fund case introduces a brand-new “functional equivalence” test for whether an indirect water pollution source is subject to the Clean Water Act. (Photo: Steve Petteway, photographer for the US Supreme Court)

BASCOMB: Now, in the interest of full disclosure, Pat, you were part of a group that files an amicus brief in this case, can you tell me about that?

PARENTEAU: Yes, a group of us law professors got together and wrote a brief and had it circulated among our colleagues, both environmental law professors and administrative law professors. And we argued for a little different test, we thought a simpler approach would be to say, as long as you can establish a proximate cause between the indirect discharge and the impact on the water. You know, we cited examples of using dye tests to be sure that the same pollutant you're concerned about is actually coming from a designated or a defined point source. So we argued for the result in the case, which was, there should be some instances where these indirect discharges are regulated. We just advocated a slightly different test, one that Justice Breyer didn't think much of. And so he literally invented this functional equivalent test, it's, it's brand new.

BASCOMB: Well, it seems to have done the job, though.

PARENTEAU: I would say so. I think you have to chalk this up as an important win for water quality and the environment. And good news from a Court that -- frankly, we're all very concerned about, whenever an environmental case gets to the Supreme Court these days, we kind of hold our breath and hope for the best and, and I think, in this case, we probably got the best outcome we could have hoped for.

Former EPA Regional Counsel Pat Parenteau teaches environmental law at Vermont Law School (Photo: courtesy of Vermont Law School)

BASCOMB: Well, Pat, how likely is it that the EPA will enforce the Clean Water Act any differently because of this ruling?

PARENTEAU: I don't think we can count on the Trump administration to become aggressive, more aggressive in enforcing these requirements. They weren't even enforcing requirements before this decision, and with this test of functionally equivalent, I would worry that this EPA might actually take a position that something that really is functionally equivalent isn't. But future EPA administrations can, of course, take advantage of this. And even more importantly, citizen suits can use this test to bring actions against problems that EPA or the state isn't addressing. In fact, that's how this Maui case came to the Supreme Court. So it's most important, I think, for citizens and community groups to protect their sources of water quality, their sources of drinking water, when the government failed to do it.

BASCOMB: Pat Parenteau is a professor of environmental law at Vermont Law School. Pat, thank you so much for taking this time with me.

PARENTEAU: My pleasure, Bobby, thanks.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth