Animal City: The Domestication of America

Air Date: Week of May 22, 2020

Horses, dogs, pigs and people mingle in a fashionable part of early 19th-century Manhattan. (Image: Carl Fredrik Akrell after Axel Klinckowström, Public Domain)

American cities were once home to large numbers of livestock: cows grazing Boston Common, pigs roaming through what’s now downtown Manhattan. Then the nineteenth century brought cultural change and reform, and a new relationship with animals. The history of this transformation is the focus of Animal City: The Domestication of America by environmental historian Andrew Robichaud, who spoke with Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering.

Transcript

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

For most of modern human history we lived alongside the animals that provided for us. Cows, pigs, sheep and goats freely roamed villages while chickens flapped at our heels. In time, many villages grew into cities and animals were relegated to farms in the country. But throughout the nineteenth century in the United States, livestock still dominated many city streets. Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering spoke with environmental historian Andrew Robichaud, the author of “Animal City: The Domestication of America.”

ROBICHAUD: Anytime really in the early to mid 18 hundred's, you would have encountered a wide range of domesticated animals living in the cities.

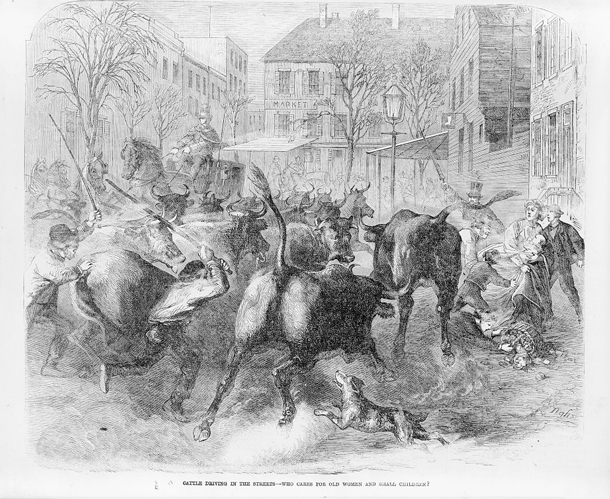

DOERING: Picture pigs roaming through the streets of Manhattan, cows grazing on the Boston Common, cattle being slaughtered right in downtown San Francisco.

100,000 horses in New York City.

ROBICHAUD: You would have perhaps seen an urban cattle drive through many of these cities. You might have also seen pigs feeding on trash in city streets, this was a really common problem in many cities, including New York, which has decade after decade of challenges regulating these pigs.

[MUSIC]

DOERING: With all these smelly, messy livestock roaming around, American cities were a bit behind European cities like London.

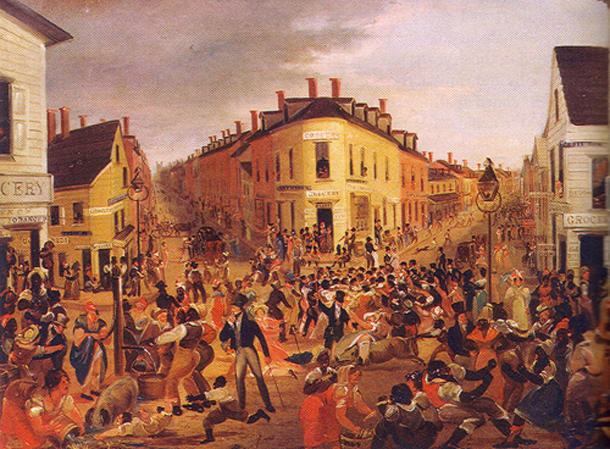

ROBICHAUD: And in fact, Charles Dickens when he comes in 1842 makes note of these pigs in New York and other cities.

DOERING: Yeah, he calls them gentlemen hogs you write in your book.

ROBICHAUD: He does he, gentlemen, hogs and Republican hogs are are sort of the terminology that gets thrown around around these pigs. And Dickens is fascinated with them. He thinks that this is just so interesting that New York is this major American metropolis, and that there are pigs mixing with these very fashionable people and very fashionable parts of town.

[MUSIC]

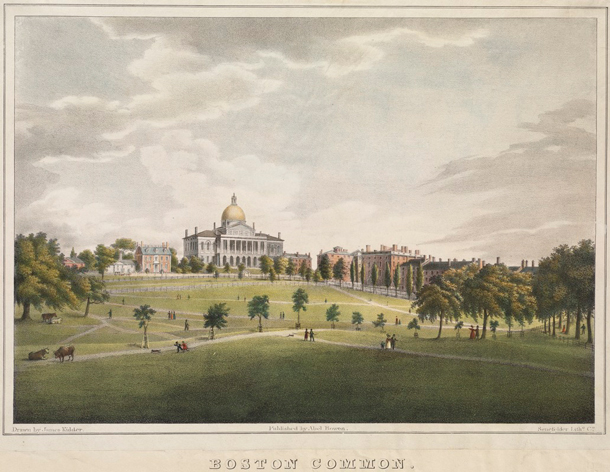

James Kidder’s 1829 lithograph of the Boston Common shows a landscape in transition from a cow pasture and multiuse space into an urban park and place of leisure. (Image: Boston Public Library, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

ROBICHAUD: He's seeing these American cities as an interesting urban form.

DOERING: American cities, at the time were rapidly expanding as immigrants arrived from Ireland, Germany, China, and more. And Americans from the countryside were moving to cities to find jobs in the quickly industrializing economy. These new urban residents weren’t coming alone.

[MUSIC]

DOERING: So Andrew, as early Americans started to leave the countryside and they were congregating in these cities like New York like Boston, San Francisco. Why did they bring their animals with them?

ROBICHAUD: Yeah, so I would rephrase that is why wouldn't they, for thousands of years, people lived with livestock. That's how they understood a main component of their subsistence their engagement with the market. It was a really central way of life, to own animals to have animals to eat animals to use animals in all different ways. And it's not completely obvious or inevitable that cities would not be places where people could have those animals. And in fact, what we see in the case of Boston, there are efforts to regulate or restrict the use of the commons for cows for many decades. And there's real pushback from a lot of people in the city to keep the Boston Common as an urban pasture.

[MUSIC]

ROBICHAUD: And so even in these developing industrializing economies and cities, they're still sort of this agrarian ideal that is part of the laws and the landscapes where people can have. If they really want it, they can still have a cow or two if they have the right lot size.

People and animals mix in this 1827 oil painting by George Catlin of the bustling Five Points neighborhood of lower Manhattan. (Image: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

[MUSIC]

DOERING: But it’s only a matter of time before keeping even one or two cows becomes impractical. As people work longer hours in factories they no longer have the time to take care of their own cows.

[MUSIC]

DOERING: And the growing population is demanding huge quantities of milk and meat. And these commodities are produced right in the city.

ROBICHAUD: Sometime in the 1820s 1830s We see the development in New York City of this massive dairy industry, located on the west side somewhere in the 10s and teens of the street grid, where they're these massive oversized barns that are keeping anywhere from 500 to 2000 cows. By one estimate, there are 18,000 cows living in these cramped feedlots in the 1840s. The conditions that the cows were kept in were so abysmal. We tend to think of feedlots as 20th century developments, but we see them in the 19th century.

“Cattle Driving in the Streets—Who Cares for Old Women and Small Children?” A depiction of a street scene in New York in 1866, showing the dangers of urban cattle drives that plagued many cities. (Image: Library of Congress)

DOERING: In what is now downtown Manhattan.

ROBICHAUD: In what is now downtown Manhattan, Yeah, yeah. So, yeah, this is the world that's emerging in New York is this really dense urban animal life as well.

[MUSIC]

You know, cows in cities might sound kind of cute and kind of interesting. But what was at stake here was the health of thousands, tens of thousands of urban residents.

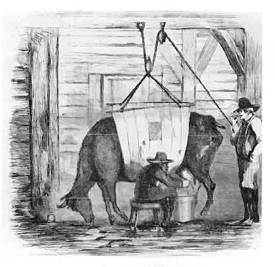

DOERING: At the time the child mortality rate was actually increasing. One suspected reason: bad milk. Urban dairies figured out they could cheaply feed their cows leftover swill, or mash, a whiskey by-product.

ROBICHAUD: By the descriptions of reformers they're producing this milk that's watery, it's blueish. Many cases these stables are actually connected to the distilleries And the mash is being piped in to the troughs of these cows piping hot as it's often described.

[MUSIC]

This 19th century illustration of “swill milk” being produced depicts a sickly cow being milked while held up by ropes. (Image: Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly, Public Domain)

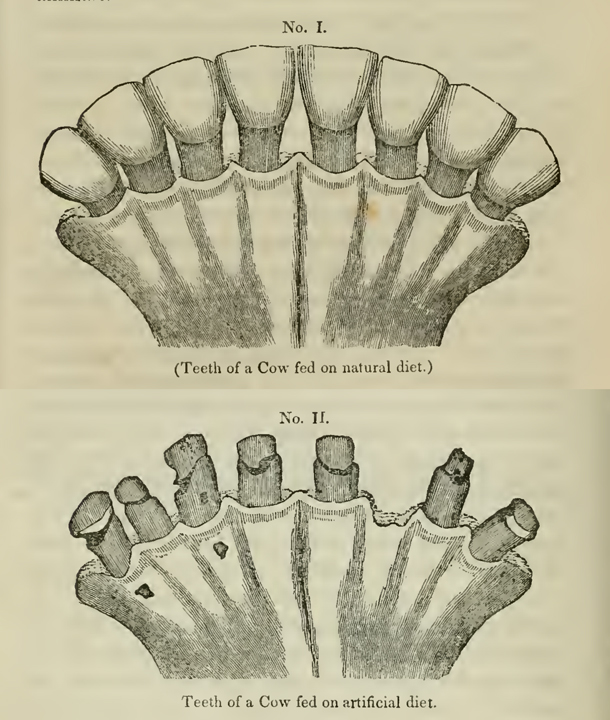

DOERING: This stuff was so toxic that the cows would refuse to eat it until they were almost starving, and then it would rot their teeth. The dairies had their ways of adding ingredients to the milk to make it lo ok more natural. They’d add chalk and plaster of Paris, that took care of the weird bluish hue; and other ingredients like molasses, sugar and eggs to mask the taste and smell. Needless to say, these additives made the milk even less healthy. And it was horror over the poor quality of swill milk that inspired the first animal ag reforms in the country, led largely by teetotalers involved in the American Temperance movement. Reformers were also deeply concerned about swill milk as a desecration of divine creation.

ROBICHAUD: The reformers in the 19th century are also thinking about this as a question of nature. And as they see it a question of nature and God's designs. And so they're really paying attention to the anatomy of cows and trying to figure out where do cows belong? And their answer is not in cities, they belong in the country they belong eating grass.

DOERING: Starting in the 1840s, railcars cooled by giant blocks of ice helped enable this for the reformers.

[MUSIC]

ROBICHAUD: And they see the railroad as this really great possibility to bring in country milk and to bring in the health of the country to reform and remake the city, both physically but also culturally and socially.

“Teeth of a Cow fed on natural diet”, above, and “Teeth of a Cow fed on artificial diet”, below, 1842. (Image: Robert Hartley, An Historical, Scientific, and Practical Essay on Milk, Library of Congress)

DOERING: But moving most milk production to the country didn’t actually solve the problems with the quality of milk. Even ice couldn’t protect against bacterial contamination, something that was undiscovered at the time. And, there were no real standards or laws for labeling milk.

ROBICHAUD: What ends up happening is that many of these urban swill Milk Producers start to advertise as country milk, they simply take that trope that's floating around society, they repaint their wagons, they rebrand and they say we're country milk. So it's really hard for consumers to be able to tell where their milk is actually coming from.

DOERING: I mean, we have a similar problem today. It sounds a lot like greenwashing.

ROBICHAUD: Yeah. It's, that's interesting. They, they certainly they didn't have the word for it at that time. But it is, I think it is an interesting example of something that's like greenwashing which is an environmental movement or an environmental reform of some kind that then gets picked up by profit driven interests and sort of twisted around.

[MUSIC]

DOERING: The quality of milk did improve towards the turn of the century as knowledge about bacteria and pasteurization grew, and regulators started requiring tests for adulteration.

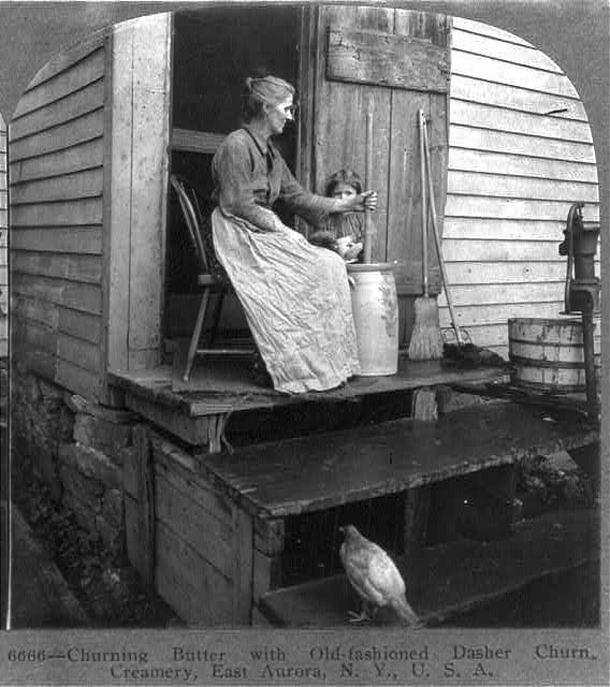

Churning butter was a labor-intensive chore performed mostly by women. (Photo: Library of Congress)

[MUSIC]

DOERING: The working animals in nineteenth century cities also included some animals we might not think of as livestock today.

ROBICHAUD: “Yeah, so this is one of the most surprising things that came out of my research was that dogs are really widely used for labor in American life in the 19th century. “

DOERING: Enterprising inventors figured out how to put man’s best friend to work pressing apples for cider, and churning butter.

ROBICHAUD: “Yeah, so you have to sort of imagine, well, there are all different models of dog machines, but one of the most common ones looks kind of like a treadmill, what they called an endless chain principle machine. And so you have to imagine a dog on a treadmill, moving the treadmill, and that's moving an arm up and down to churn butter. “

“And what's really interesting about this is that it also reflects some deeper changes happening in American life at this time. Churning butter was traditionally work that many women did in an agricultural society in America. And what's happening is that these dairies are growing and producing for markets for urban consumers in many cases in the 19th century in the 1800s. And dogs are doing that work.

[MUSIC]

ROBICHAUD: And so all these agricultural journals are touting the possibilities of dog labor, that dogs will save women from having to do this hard work of churning, which now takes many many hours rather than just a short amount of time.”

DOERING: But some people were concerned about the ethics of using dogs for labor, and in 1874 a high-profile trial in New York City charged the owner of a bulldog put in a cider press machine with animal cruelty.

ROBICHAUD: And it gets at questions of what is a dog is a dog, a creature of labor? is a dog, an animal that we can put to work in different ways?

[MUSIC]

A butter churning dog machine from The Boorman House in Mauston, Wisconsin. (Photo: Sixa369, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

ROBICHAUD: Or are dogs, creatures of leisure, are they pets, and that's really what's at stake here.

DOERING: SPCAs, Societies for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, were pushing for dogs as pets, along with better conditions for more traditional livestock like cows, pigs, and horses. George Angell and Henry Bergh founded the first SPCAs in the 1860s, which were largely inspired by a similar movement in Great Britain. These organizations gained considerable power as quasi-governmental animal welfare enforcement agencies, and this type of labor stopped. But their powers only went so far.

ROBICHAUD: And so that dog case that I talked about, where there's a dog who's running this cider press, he's running this machine. The SPCA intervenes, they stopped the owner from doing that. A week later, the owner has put into the treadmill, an eight year old black boy who is now doing the same work that the dog was doing and the SPCA can't do anything and they can't touch it because it's not part of their purview. And so there is this interesting overlap of the development of child protection and animal protection. And in fact, in New York, the SPCC Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children is founded after the SPCA and it's founded by most of the same members who realized that they need to create a structure to also be able to prosecute and protect children as they have for animals.

[MUSIC]

DOERING: On America’s other coast, the government is cracking down on slaughterhouses.

ROBICHAUD: Yeah, so this was a big public battle. In the 19th century. They called it the war on butchers in city newspapers and city newspapers covered it quite intensely.

DOERING: We’re at a time in San Francisco’s history when the population is swelling with gold seekers and Chinese immigrants. And the slaughterhouses are being swallowed up by the growing city. The stench of this industry becomes unbearable for locals.

ROBICHAUD: “And what they're doing in San Francisco is they're really saying slaughterhouses and livestock can't operate in large parts of the city and they end up creating a slaughterhouse district in San Francisco. It's called butcher town. But we see this happening in just about every major American city in the 19th century.

The buildings of San Francisco’s Butchertown, constructed on stilts so that they could release waste straight into tidal waters, fared poorly in the 1906 earthquake. (Photo: DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University, Wikimedia Commons)

DOERING: Butcher town became a throwaway place, a part of town where all the noxious animal industries ended up: hog ranches, tanneries, slaughterhouses . . . This district was on the outskirts of San Francisco near the water.

ROBICHAUD: “They're trying to tap into natural features of the landscape, especially water, and saltwater, if you can get it but river water otherwise, as a cleansing agent, they think that the prevailing winds are going to carry all of the miasma as they think of it is really dangerous fumes, unpleasant smells out over the San Francisco Bay, where they'll dissipate, and where they won't cause harm to people.

DOERING: “Yeah, it sounds like a the solution to pollution is dilution kind of mentality, right? Yeah. But I mean, did that cause problems ultimately for the health of the bay?”

ROBICHAUD: “Yeah, so the plans of reformers don't actually work out as they had imagined as, as you might have guessed.

[MUSIC]

ROBICHAUD: Like many environmental problems, there are unintended consequences.

DOERING: More and more slaughterhouses and butcheries are cropping up, and at some point they just overwhelm the system. At the same time, sewage from the growing city and mining waste from far upstream were pouring straight into the same, inky black baywater. And locals were getting pretty fed up.

The cover of Animal City: The Domestication of America (Image: Courtesy of Andrew Robichaud)

ROBICHAUD: “ And what's interesting in San Francisco in many other cases is that the government is not going after the polluters. They're going after the people who are using the lands that are polluted. “

DOERING: People like immigrant dairy farmers and Chinese shrimp farmers. The large-scale butcheries and tanneries were basically given a free license to pollute, while small scale producers, who were also dealing with the added cost associated with some of the new regulations were finding it impossible to compete. Polluting fines were the same regardless of the size of the producer. They were a drop in the bucket for large companies, but put many small, family owned producers out of business.

[MUSIC]

ROBICHAUD: I think there really is an environmental justice angle to this project as well, because in 1888, the city passes a law that says that Chinese residents can no longer live downtown they have to live outside of the city and where do they choose to put Chinese residents? Well, they say they have to live in butcher town. In the 20th century is where the city builds a sewage treatment plant. And it's actually a place to where public housing is built largely for African Americans in San Francisco who where being uprooted and removed from downtown. These spaces that are carved out in the 19th century to accommodate these animals suburbs are concentrated animal populations and life and death. They go on to have this long legacy of being redlined in many cases, sometimes they're explicitly redlined. For the smells that they're producing,”

[MUSIC]

DOERING: So by the 20th century, reformers had successfully exiled slaughterhouses and dairies from cities. Urban livestock were almost history, although horses still trotted through city streets until the age of the automobile.

DOERING: So Andrew, kind of looking big picture. How can looking into the history of the animal city help us understand the human animal relationships that we have today?

Andrew Robichaud’s next book project is a history of climate, ice, and the ice trade in nineteenth-century North America. (Photo: Courtesy of Andrew Robichaud)

ROBICHAUD: Yeah, well, I think that people living in 19th century cities were really on the forefront of a major change in human history. In many ways, most of us live in the shadow of this world that was created by 19th century reformers who really wanted to create spaces that were clean that were pleasant to be in that were free of brutality and free of blood and free of unpleasant smells.

DOERING: Andrew Robichaud says the brutality is still there, it’s just out of sight, out of mind. And in fact most of our meat and dairy come from CAFOs, Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations, far away from major population centers.

ROBICHAUD: And so this was one of the things that drew me into this project in many ways is that we have this modern landscape of human animal interactions that is so spatial, which is to say we have these really visible and really close relationships with pets with animals that many people treat almost like people. And then we also have this really massive and largely invisible world of feedlots and stockyards and slaughterhouses. This is really a feature of modern life and modern human animal relationships.

[MUSIC]

DOERING: Andrew Robichaud’s next project has a working title of On Ice: Transformations in American Life. It’s a history of climate, ice, and the ice trade in nineteenth century North America.

[MUSIC]

BASCOMB: That’s Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering, speaking with Andrew Robichaud, author of “Animal City: The Domestication of America”.

Links

“Animal City: The Domestication of America” by Andrew Robichaud

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth