Judge Barrett and Environmental Law

Air Date: Week of October 9, 2020

President Trump nominated Judge Amy Coney Barrett for Associate Justice of the Supreme Court on September 26, 2020. The nomination was announced in the Rose Garden of the White House. (Photo: The White House, Amy Rossetti, Flickr, Public Domain)

Supreme Court nominee and Federal Appeals Court Judge Amy Coney Barrett is a conservative who tends to interpret the law narrowly, meaning that if she is confirmed, she would generally rule against innovative environmental advocacy legislation. Patrick Parenteau, a professor of environmental law at Vermont Law School, joins Host Steve Curwood to talk about Judge Barrett's record and how she might approach environmental litigation on the high court.

Transcript

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Republicans are trying to rush Senate confirmation hearings for conservative appeals judge Amy Coney Barrett to replace the late Ruth Bader Ginsburg on the Supreme Court. The hearings, set to begin October 12, come amid a coronavirus outbreak that includes the President and dozens of Republican officials including 3 senators on the Judiciary Committee. Many of the people linked to the White House outbreak attended Judge Barrett’s announcement September 26th in the presidential rose garden. Judge Barrett is an acolyte of the late conservative Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia and at age 48 she would become the youngest justice. Strictly conservative justices more often than not rule against innovative environmental advocacy litigation. To explain how that works we turn now to Vermont Law School professor Pat Parenteau. Welcome back to Living on Earth Pat!

PARENTEAU: Thanks, Steve, pleasure to be with you.

CURWOOD: So please take a moment to walk us through a role that a Supreme Court justice plays when it comes to environmental matters.

PARENTEAU: Well, the first rule is to see whether or not Congress, when it passes environmental laws, is acting within the constraints of the Constitution. Most of our environmental laws are based on the Commerce Clause. US Congress doesn't have what states have, which is broad police power authority to protect public health and welfare, and so forth. Congress has to ground the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act and all of our environmental law is in some kind of impact on interstate commerce and that comes into play big time when you're talking about the Clean Water Act. And whether or not Congress can go to the limits of the Commerce Clause to protect the headwaters, let's say of our, our watersheds, the small rivers and streams and wetlands that make up the full aquatic ecosystem. A judge like Judge Barrett, who's a self-professed originalist, takes a fairly narrow view of Congress's authority under provisions like the Commerce Clause. So that will be something to really watch early on, when, as we know, some of the anti-regulatory forces will begin challenging not only the rollbacks that Trump has put in place, but even going back to some of the prior rules that were in place, under President Obama and others. Some of those rules could be at risk with a strict constructionist, when it comes to the Constitution.

CURWOOD: So what is Judge Barrett's voting history, which could indicate her stance on matters that are likely to come up and in cases involving the environment?

Amy Coney Barrett sits on the Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit in Chicago and was a professor at Notre Dame Law School. (Photo: Rachel Malehorn, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 3.0)

PARENTEAU: Yeah, we have to look mostly at what she has said in her writings. She was a law professor for many years at Notre Dame law school on the Seventh Circuit where she's been for the last several years. She has not actually written any majority opinions dealing with environmental law but she is very outspoken on matters of constitutional interpretation, and particularly statutory interpretation. And because she is described as a protege of Justice Scalia, she said in accepting President Trump's nomination, I intend to follow the lead of Justice Scalia, in the way I approach my job if I'm confirmed. And what that means is when it comes to interpreting statutes, Justice Scalia was a textualist, as is Judge Barrett, which means that you don't so much look to the purposes of the laws that Congress enacts, for example, the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, the Endangered Species Act, most of these laws have very strong environmental objectives and purposes. And sometimes the words of the statute don't fully reflect the policies and the purposes that drove the law to begin with. And that's where the words of a statute become critical. A judge, like Judge Barrett would not necessarily pay much attention to the statement of purpose or policy, she would zero in on the narrowest definition of the word in question. So that could really limit federal power to protect natural resources.

CURWOOD: So what are some of the cases that are likely to come up fairly soon with this, if we end up with a, basically a six to three conservative Supreme Court to deal with them?

PARENTEAU: Yeah, let's talk about the climate cases, because those are the ones that are, I think, going to be most at risk. The Trump administration, of course, repealed Obama's Clean Power Plan, which was one of the major features of his attempts to deal with climate change. And it's been replaced by something called the Affordable Clean Energy Act, which is a misnomer but that's what it's called. And it doesn't do anything at all, to deal with climate change and in fact, it increases the threats to public health by allowing a lot of dirty old plants to continue to operate. So that case is now being argued in the DC Circuit Court of Appeals. And from there, it's almost certain to go to the Supreme Court. And that's going to put front and center what exactly is the power of the EPA to use the Clean Air Act to deal with climate change to deal with power plants. And the rule that's right behind it is the rule dealing with automobile emissions and fuel economy standards. And once again, the Trump administration has rolled back the Obama rules which was driving us towards 50 miles per gallon, with much cleaner vehicles, electric vehicles, and hybrid vehicles. Trump has rolled all that back to about 28 miles per gallon. That's going to end up in the Supreme Court and that'll be another question both of what's the scope of EPA's is authority under the Clean Air Act, but in the case of the tailpipe standards, it also raises the question whether California which has historically been given an extra authority to deal with air pollution given their very severe air pollution problems in the Los Angeles Basin, there's also going to be a question of whether the Trump administration's revocation of California's authority to set stricter standards would also be overruled. That is to say California's is attempts to regulate would be struck down, that would eliminate one of the most potent federal tools, we have to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. And then there's the methane rule right behind that, and whether or not EPA can regulate methane coming from oil and gas wells across the country. So just looking at that one issue of the Clean Air Act, and climate change, there are three cases lined up, all of which could potentially get to the Supreme Court in front of this new 6 - 3, almost ironclad conservative majority of the court.

CURWOOD: There's been some discussion that if the Democrats in fact do take the White House and the Senate along with the House that they might want to expand the Supreme Court, say to 11 and appoint two more justices and shift the balance. Your views?

PARENTEAU: So I know that's very much in discussion and tempting, I'm sure if the Democrats do take control of the government, but the problem with that is you're going to have an endless sequence of people continuing to change the number of justices on the court, depending on who's in power. So I'm not sure that that's a really good long term solution as tempting as it may be. There's also some discussion about term limits and limiting the terms of justices on the court that might have more appeal. I mean, I think actually, that makes some sense. It won't help with the current members of the court, though, they're not going to retro actively impose term limits on people that were appointed for life. But in terms of future appointments, maybe term limits would make some sense.

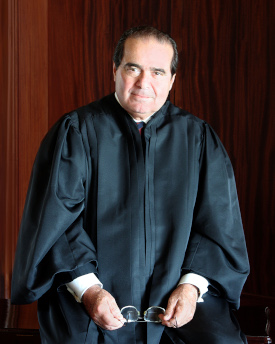

The late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia played a crucial role in the landmark climate change case Massachusetts v. EPA. (Photo: Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States, Flickr, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: There's been some cynical remarks saying, well, Trump is designating Judge Barrett because she's a woman and she's young. So she'll be around without necessarily revealing her qualifications. From what you know, how sharp a jurist is, she Scalia was very conservative, but also very smart.

PARENTEAU: Yeah, I think I'd have to say she's also very smart. And she's also very candid, frankly, I've read two of her articles, just to get a sense of does she confront the other side of the positions that she's taking? And she does. She frankly acknowledges when it comes to questions of statutory interpretation, that it's a very difficult job for the court to perform. because you're on the one hand, courts are supposed to be deferential to the legislative branch. But on the other hand, they're supposed to exercise independent judgment about what the words of a statute mean. And you could certainly find interpretations of statutes that go against what the real intent of a Congress was. I mean, when you look at environmental law, it's always responsive. I mean, we didn't pass the Clean Water Act, until we had rivers catching fire. We didn't pass the Clean Air Act, until people were literally choking in the smog of Los Angeles. The point being, Congress is often reactive to these problems. And when they pass laws, they can't envision all that has to be done in order to deal with them. That's why they leave to agencies discretion to let laws sort of evolve and adapt as time goes by. But a doctrine that says we're going to stick to the original intent and words of the statute, we're not going to try to take into account these broader goals and purposes, that cuts directly against what Congress is trying to do with environmental law, which is oftentimes remedial in nature and long term in nature. Barrett has acknowledged that tension she has said, you know, judges face a difficult job of balancing their duty to the Constitution, to say what the law is, but also to be respectful of the fact that legislators sometimes have to enact laws that are very general in their scope, and that don't have all the specificity that you might want. So I think she's an honest, although conservative judge, I would not discount the fact that she could evolve and grow as a justice, but clearly she's going to start from a place. That means environmental law in particular is going to have a very hard time you have to understand an awful lot about the science and the technologies or the technical aspects of environmental law, you really have to spend time trying to understand what environmental law is trying to accomplish in order to fairly interpret it. I'm not sure she's open to that kind of exploration of what is the law of trying to do. If she's going to take this approach, if all I want to do is determine what this word means she's going to miss an awful lot of the nuance that goes with environmental law.

CURWOOD: These days, you see a bill come in front of the Congress, and it's as thick as a book, or maybe even a stack of books that seems that nobody actually reads through. To what extent does Congress now have to start paying a lot more attention to really understanding what it's passing?

PARENTEAU: Oh, I think that is absolutely right. You know, when Congress passed the Clean Water Act, they invented a term waters of the United States. They didn't define it they didn't know what it meant. That's clear from the legislative history. It was kind of thrown in at the last minute in the conference report. That can't happen anymore. The Supreme Court's not going to pass that. Congress is going to have to do the hard work of figuring out what it wants the agencies to do, and spelling it out in plain English, understandable English. and, you know, that's just the way it's going to be and if Congress doesn't do that, you're going to find the Supreme Court making decisions based on what they think the words mean, not necessarily what Congress was trying to accomplish.

CURWOOD: Pat Pareteau is a professor of law at Vermont Law School. Pat, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

PARENTEAU: Good to be with you, Steve. Thanks.

Links

Politico | “What Amy Coney Barrett Could Mean for Climate Law”

E&E News | “Could Barrett 'Shut the Courthouse Doors' on Enviros?”

Learn more about Justice Scalia’s role in Massachusetts v. EPA

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth