Enduring Against Seemingly Impossible Odds

Air Date: Week of October 9, 2020

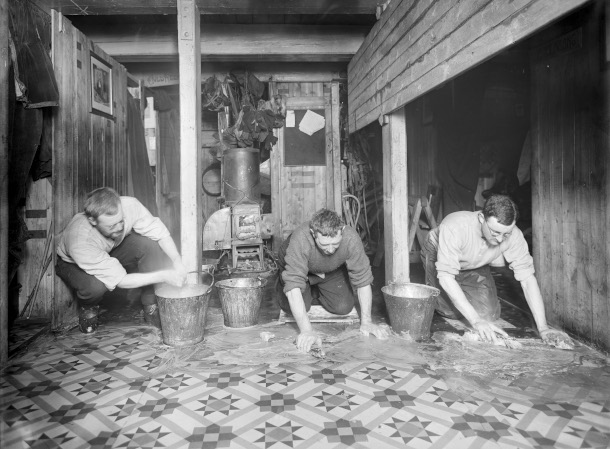

When ‘Endurance’ got trapped in sea ice, the crew aboard the ship kept their minds and bodies occupied by keeping up with their daily activities. (Photo: Manchester City Council, Flickr, CC BY NC ND 2.0)

In 1914, British explorer Ernest Shackleton and his crew of 27 men set sail for Antarctica. Disaster struck when their ship the “Endurance” became trapped in pack ice and later broke up, yet optimism and sheer perseverance carried all 28 men through what seemed impossible odds. Rosamund Zander, the author of Pathways to Possibility: Transforming Our Relationship to Ourselves, Each Other, and the World, joins Host Steve Curwood to talk about how Shackleton used emotional intelligence to keep his crew going through and how we can all harness an optimistic mindset to carry us through difficult times.

Transcript

CURWOOD: 2020 has been challenging, to put it mildly. The rising death toll from the virus pandemic is horrible, the mega storms and fires related to climate disruption are awful, the economic downturn is appalling and the social unrest linked to confronting systemic racism adds to a growing sense of uncertainty. In times like these it can be helpful to hear stories of people who survived extreme difficulties and how they did it. Rosamund Zander has written a book about just that, it’s titled Pathways to Possibilities: Transforming Our Relationship to Ourselves, Each Other, and the World. Roz says the key to getting through hardship is to work in ways that maximize the chances of having a good outcome. It’s not enough to just think positively, she says. One must take direct action and seize every opportunity to make things better. Roz Zander, welcome to Living on Earth!

ZANDER: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: Our pleasure. So let's face it, these are some difficult times, right? I mean, COVID-19 has pushed the world into a quarantine, that was unexpected, and a lot of people have fallen economically insecure. In your Pathways to Possibility there is a delightful set of stories to talk about dealing with, shall we call them difficult situations, how to overcome them and push through. And so what's the story you'd like to share with us from your book that resonates the most with these times?

ZANDER: Well, it may seem odd to you, but I think of a story about Ernest Shackleton. He was a British explorer, and living in the beginning of the 20th century. And he had an idea that he wanted to go explore the Arctic. And the first thing he did was to put out a job description. I'm going to read you his job description "men wanted for hazardous journey, small wages, bitter cold, long months of complete darkness, constant danger, safe return doubtful, honor and recognition only in case of success."

Men from the ship’s crew playing soccer while the ‘Endurance’ was trapped in sea ice. (Photo: Manchester City Council, Flickr, CC BY NC ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: [Laugh] So that sounds very difficult. Why? Why was it going to be so difficult?

ZANDER: Well, he got 28 men signing up with that kind of advertisement. They must have had a lot of adventures and thoughts, but it was much more difficult than they expected. And they set sail in Shackleton's boat, which was called the Endurance quite appropriately on August 6 1914, from the coast of England. Four months later, they were heading south on the coast of Antarctica and hit dense polar ice. By the end of January, the boat got totally trapped in the pack ice. And they had to wait there for 10 months patiently for a thaw in the ice because they couldn't move. After 10 months, the ice crushed the ship. Are we looking for troubles?

CURWOOD: Yeah.

ZANDER: So these 28 men camped on the ice for five more months, waiting for open water and enduring terrible hardships. Finally, they were able to sail their three lifeboats which they had rescued from the crushed ship to an uninhabited piece of rock called Elephant Island from which there was absolutely no hope of rescue.

CURWOOD: So no way to get off this island, huh?

ZANDER: No way to get off, except that they had their lifeboats. And Shackleton acted very quickly, because he knew that men were almost at the end of their ropes here. And he took five of them in a 22 foot lifeboat and set out on an impossible 800 mile journey through the world's worst seas at the worst time of year.

CURWOOD: What about the men who are being left behind? I mean, here they are, in this very difficult place their leader has left in this boat kinda doubtful the boat's going to get anywhere successfully. I mean, this is complete desolation.

ZANDER: It is, and they were left in the charge of Shackleton's first mate named Frank Wilde. And he understood how to lead men. And so as the men were waiting on the shore and watching the boats go off in the distance, some of them got tears in their eyes. And Frank Wilde got them to work immediately.

CURWOOD: So I guess we know this story because Shackleton must have had some success with that tiny boat on those big seas.

The Endurance, trapped in sea ice along the Weddell Sea. (Photo: Manchester City Council, Flickr, CC BY NC ND 2.0)

ZANDER: You're right. You know, the ending is going to be good, but it still has some lessons in it. So Shackleton realized they had to act quickly to get help. And so he took off in a 22 foot lifeboat, with five men, leaving the others behind. He set out on an impossible 800 mile journey through the world's worst seas, and that the very worst time of year. They aim for the nearest populated territory, which was South Georgia Island, and its whaling station. And they got there, but they landed on the wrong side of the island and had to climb 26 miles over the mountains and over the glaciers to get to the whaling station. It's hard to believe. They were hardly recognizable by the people working in the whaling station. They were so emaciated. They hardly looked like human beings. And then of course, Shackleton knows he's left 23 men behind and he gets into a sea worthy boat as soon as he can, and goes back the 800 miles to elephant Island.

CURWOOD: So what was the condition of those men who've been left behind?

ZANDER: Well they had suffered injury and infection, hypothermia, attacks by an elephant seal near starvation, completely unspeakable conditions. But not one member of the original 28 man crew was lost, not one, but the sink. How is that possible? Really? That's the question. And our best clue is that Shackleton remained consistently positive in his outlook and forbid the expression of negativity or despair. He declared, and when I love this, he declared that optimism is the true moral courage. Optimism is the true moral courage. Both Shackleton and Frank Wilde understood that they had to be completely disciplined with the men in keeping them from saying anything negative or going into despair, because that's the way they would survive. If there was a negative story hanging around and people were playing with it, "are we gonna make it?" they would very likely all have died in a short order time.

CURWOOD: So Roz why is it that in times of peril and stress, our minds tend to wander towards the negative thoughts instead of immediately jumping in to optimism?

ZANDER: Well, because we're wired that way. I meam it is a fear response, negativity is a fear response. You can't help but think of the possible dangers. Nature wants you to do that up to a point. But in such a time as COVID, or such an adventure as Shackleton's, it isn't useful. And you can overcome that wiring. But it takes discipline and effort to overcome it, you have to stay consistent of saying, tomorrow will be a better day. And that's the truth, as we know it.

Rosamund Stone Zander is the author of Pathways to Possibilities: Transforming Our Relationship with Ourselves, Each Other, and the World. (Photo: Courtesy of Rosamund Stone Zander)

CURWOOD: So when it comes to optimism, how important is it to be active about this as opposed to you know, just having an optimistic attitude and, and sitting there?

ZANDER: Well, it's very important because it's a disciplines what you're doing in optimism is overriding the wiring that we are given at birth, and to override wiring, it doesn't actually take you running around but it does take mental activity to do that. And then of course, telling other people to do the same. It's making a community keeping a conversation going, that lifts others as well and it does wonders for the immune system. actually. If you have a group of people who are all speaking in possibility, their physical state is different than those who are all in despair, it's completely different. And their immune systems are strengthened by optimism, not by positive thinking, not by lying to themselves. And optimism and positive thinking are quite different positive thinking occurs when you really know that something is bad, but you're hoping it will not be and you're going to pump yourself up to say it isn't but that's a lie. Positive Thinking is a lie. Optimism in the face of you could die or you could live the options are open, the future is open, you don't know the answer so that's not a lie that kind of optimism.

CURWOOD: Let's go back to Shackleton for a moment. How would the situation with Shackleton's men differed if they'd act based on positivity and not optimism? Do you think?

ZANDER: Well, the thing is that it's a lie and therefore it would show through. Somebody would be going into despair, and not know what to do about that. Whereas every man on this journey, knew what to do. They had to speak the story of survival that we are going to survive. And what happened was that they became very collaborative and when one man spilled his cup of milk four others rush to fill it up again, even though they were all starving.

CURWOOD: Well, I want to thank you for taking the time with me today. Rosemund Stone Zander is on Pathways to Possibilities: Transforming our Relationship with Ourselves Each Other and the World. Thanks so much.

ZANDER: Thank you so much. It was a great pleasure.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth