Teddy Roosevelt’s Conservation Legacy

Air Date: Week of February 5, 2021

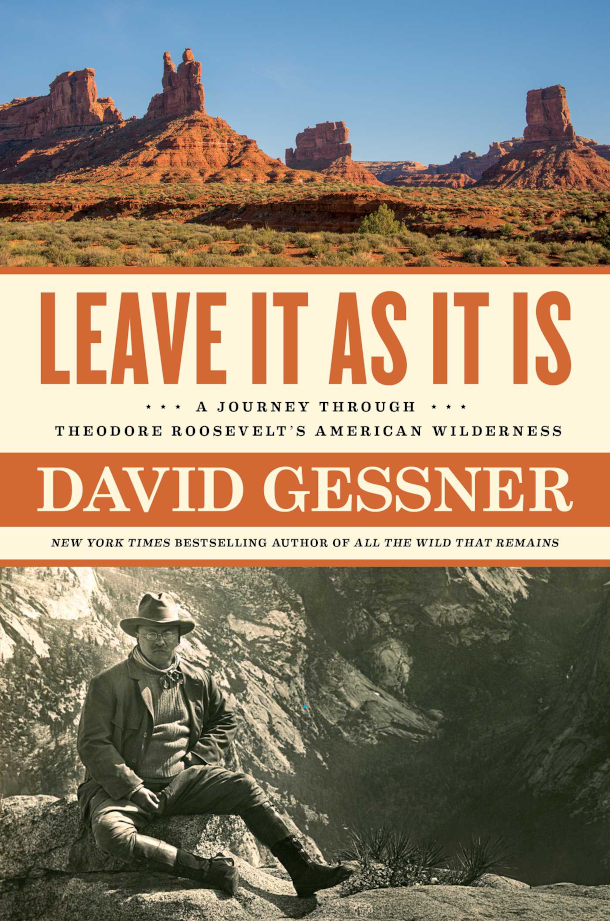

The cover of Leave It As It Is: A Journey Through Theodore Roosevelt’s American Wilderness. (Image: Courtesy of Simon & Schuster)

President Theodore Roosevelt’s famous rallying cry to “Leave it as it is” upon seeing the Grand Canyon for the first time continues to inspire conservation today. But his racism casts a shadow over his legacy in a time when conservation is being reimagined with more diversity and inclusivity. In his 2020 book Leave It As It Is: A Journey Through Theodore Roosevelt’s American Wilderness, author David Gessner reevaluates TR’s vision for today, and joins Host Jenni Doering to discuss.

Transcript

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth I’m Bobby Bascomb

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering

In 1903 President Theodore Roosevelt shouted through the wind as he stood at the rim of the Grand Canyon and delivered a famous rallying cry for conservation. “Leave it as it is,” he said. “The ages have been at work on it, and man can only mar it”. TR acted on those words and preserved over 230 million acres of public land using the Antiquities Act. But President Roosevelt was a flawed man. He was racist and a known eugenicist who viewed white Americans as superior, and believed Native Americans had no rightful place on their lands. Despite Roosevelt’s deeply troubling views on race, he still has a lot to offer us in a time of renewed calls for conservation, says writer David Gessner. He’s the author of Leave It As It Is: A Journey Through Theodore Roosevelt’s American Wilderness and he joins me now. Welcome back to Living on Earth, David!

GESSNER: Thank you. It's great to be back.

DOERING: So what exactly did Roosevelt do for conservation, David?

GESSNER: Well in a way he created it. I mean, he created the idea of it, he created the arena in which it was fought. Certainly there had been land saved and parks saved before him. But the fervor with which he took it on, I mean, he made it one of his top three goals of his administration. We never had that before or since with a President. And what you have, you know, in the end, he saved 230 million acres of public land. And he did it in a variety of ways. But perhaps the one most linked to him is the Antiquities Act, is the act through which presidents can save national monuments. It's a misconception that Roosevelt created that act, he did not. But Congress created it in 1906, and Roosevelt went right to work. Many of the traditions of that act started with him, including proclaiming monuments on your way out of office, which he did, and proclaiming larger and larger monuments, notably the Grand Canyon, where he said, "Leave it as it is," where he proclaimed 800,000 acres.

The Grand Canyon, where President Theodore Roosevelt declared “Leave it as it is” in a famous speech. TR designated Grand Canyon National Monument in 1908 and President Woodrow Wilson signed it into law as a National Park in 1919. (Photo: Scott Taylor, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

DOERING: So David, why study Teddy Roosevelt? What do we gain from looking back through time at a man who seems almost mythical today?

GESSNER: I was thinking, hey, I've written ten books about the natural world. Maybe it's time for me to start fighting for the natural world, maybe it's time to put up or shut up, basically. And I thought, this is a pretty good character, for all his flaws, for all his contradictions, is a pretty good character to use as a role model, if I'm going to start getting in some battles.

DOERING: What kinds of battles were you hoping to get into?

GESSNER: When I moved out to Colorado when I was 30, I spent a lot of time traveling over to Southeast Utah, and I really fell in love with the Anasazi ruins and red and orange rocks. And, you know, I was just recovering from testicular cancer. And there was something tied to my recovery there, something, a feeling of excitement and health and all. And so I started to write about it. And many years later, in Obama's final term, in 2016, I was asked to write about that landscape in an anthology that was being used to support the idea of Bears Ears National Monument, and that anthology was given to all members of Congress, in the attempt to get this through. And in December of 2016, when Obama declared Bears Ears a National Monument, it was this great empowering and personal feeling, the personal tied to the political, that was so exciting for me. And then nine months later, when Donald Trump was president and Ryan Zinke was the Secretary of Interior. And he declared, in front of a portrait of Teddy Roosevelt, on Teddy Roosevelt's birthday, and claiming he was a Teddy Roosevelt Republican, that he would un-declare 85% of Bears Ears National Monument, the feeling was a little bit like, you know, being lifted high and slammed to the ground. And it was on that day really, that the book was born. And that day, I kind of decided that I was going to fight for that place and write about that place. And since Roosevelt was so linked to the story, I would use him as kind of my guide and model.

Theodore Roosevelt (front right) on an outing in Colorado, c. 1905 (Photo: Harry H. Buckwalter, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

DOERING: So of course, much of this book centers around Teddy Roosevelt's relationship with the lands and people of the American West, where most of the public lands in this country are, and the journeys that he undertook there. What was it about the West that really captured the imagination of TR and so many others?

GESSNER: Well, I think it's, you know, it's almost a cliche of the American going from East to West, and I lived it out, as I mentioned, when I was 30. And it coincided with a return to health for me. And I don't think that's that unusual. Roosevelt had an incredibly tragic 24th year of his life, when, in one day, he lost his mother and his wife, and he retreated into himself. And then he retreated and left the East behind and moved to the Badlands. A lot of people think of that as an exhilarating, thrilling time. And it's been written about that way by Edmund Morris and other biographers. But it was also a kind of exorcism, right? He, he was trying to get rid of, of what he'd left behind, the ghosts that were haunting him. And being Teddy Roosevelt and being hyperkinetic, he did it by throwing himself into, you know, ranching, into hunting, into being out in the wilderness. And he really felt himself kind of remade. He later said he never would have been president, if it had not been for his time in the West. And you also have him, you know, he'd always loved the natural world, and he'd always loved nature, but you have him falling in love with big wilderness. And so, Roosevelt would come back and save those lands he loved.

DOERING: Mmm. And he also knew them intimately, I think; he knew about the wildlife that he found there. You know, he's mythologized as this macho hunter and you know, trophy hunter. That's the first thing that you see if you visit his old house in Sagamore Hill, I think is the grizzly, mounted heads of some of his safari kills. But this other side of him was Roosevelt the naturalist. Can you tell us a little bit about that and the knowledge that he had?

Comb Ridge, an 80-mile-long angled sandstone formation, is a key feature of the Bears Ears National Monument and home to ancient Native American ruins. (Photo: Bob Wick, BLM, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

GESSNER: Well, he really started out as kind of a geek. You know, he didn't dream when he was young of being a statesman or soldier. He dreamed of being a field naturalist, like his hero, Charles Darwin. And, you know, this is somebody whose life changed when he saw a seal being pulled up on a fishmonger's table in New York City, and started studying it, measuring it. And then his world breaks wide open when he's 14, and he gets a gift of glasses, which helps him see the world better. And a gun, which helps him kill things. And just like Audubon before him, as a birder he would shoot birds to study them. But he loved birds, he loved bird sound, he loved the birds' music, and it changed him completely. He started to write because of birds. And to me, that's really fascinating. I mean, there's the famous story of him rushing into a Cabinet meeting, and saying he had important news, and they all wonder what it is -- "Are we at war?" and he said, "I just saw a chestnut-sided warbler, and it's only February!" So to me, Roosevelt's important now, because he gives us a model of someone who believed in science, someone who believed in large landscapes and ecosystems, and someone who, despite his prejudices, escaped one of our most obvious prejudices of all, which is anthropocentrism, the belief that man is most important. Here was a guy who, in the Oval Office, who believed that worlds beyond the human world, worlds of animal fungi, lichen, trees, that they mattered. And to me to have somebody like that right now, who could articulate for us why the climate fight is so important, because remember, that was one of the great things Roosevelt did. He invented the environmental fight in many ways. He gave us a language to think about it, you know, for our children's children. And I believe he could do the same thing today in the climate fight. Very good at digesting large amounts of information, and then putting them in simple inspiring language. And I guess one thing I really wanted to try to do with this book was inspire people and get them out there to fight.

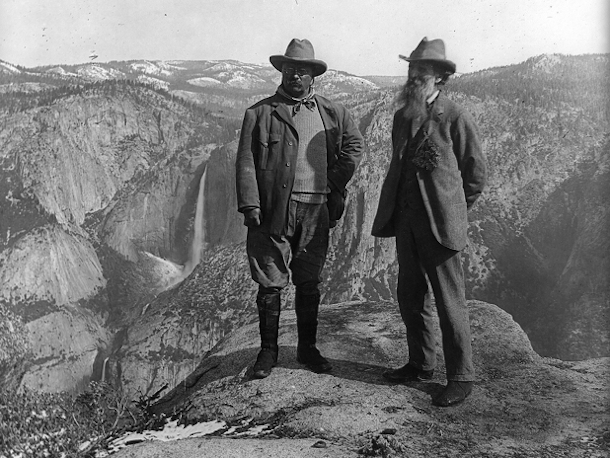

DOERING: So David, one memorable passage in your book Leave It As It Is details Roosevelt's meeting with the famous naturalist John Muir, where he abandons most of his entourage in San Francisco, to head into the mountains with Muir and a few guides and porters. Could you read some of that passage?

President Theodore Roosevelt, left, with naturalist John Muir at Glacier Point in Yosemite, 1906. (Photo: Underwood & Underwood, public domain)

GESSNER: Sitting around the fire, the two men talk. And talk. The president, by force of long habit, guides the conversation with polished monologues--his clipped sentences snapping off like the pine cones bursting in the fire--that sound as if they had been revised at his desk. He shoots words like rivets. The prophet is no less a pontificater, and also, through habit, used to having the floor. For both of them listening means waiting your turn to speak. Sometimes they can't wait and so barge right in. "Both men wanted to do the talking," one of the park rangers in attendance will remember. Their words clash against each other like waves around a point.

DOERING: So David, what did John Muir mean for Teddy Roosevelt and the environmental movement that followed?

GESSNER: You know, Roosevelt, I always think of him as kind of in between Muir on the kind of more left side, and Gifford Pinchot, his Forest Reserve director, on the other side. And Muir spoke, you know, in this kind of, as I say, religious, awe-filled language that I think Roosevelt started to adopt more and more. In that chapter that that passages from, I suddenly appear and pop into their world as they sit around the fire. This is a famous camping trip they took in the middle of his presidency, and they deserted all the press and the fancy folk who were having a big fundraiser and hiked up into Yosemite. And they camped out in the open, five inches of snow fell on them one night, they hiked into a blizzard. And they sat talking around a crackling fire. So in my little fictional interlude, I come popping in and I tell them of, you know, where the world has gone. I tell them about climate change. And I also call them out on some of the things where, if we're going to give Roosevelt credit for being ahead of his time, on environmental issues and being prescient. We have to call him out when he was behind his time. And both men were chauvinistic and, and were also very lacking in their appreciation of the native people who'd lived on the land before. You know, it's a standard biographical move, to bring up a flaw, excuse somebody or move briskly on. And with some of these issues with Roosevelt, I just let them sit there and say, Look, this is a complex, messy, hypocritical, but brilliant and accomplished, and very important person. And I think we have to be more comfortable with sloppiness, and extend some historical empathy. At the same time, we got to call people on things. I mean, I want to take from their lives, something we can use now, in the age of the pandemic, in the age of climate change. So I say they give us kind of a rough draft of a wilderness vision. There are things that are wrong with it, and their lack of empathy toward native people is a huge problem with that vision. But there are things that are great about it, too. So I want to discard what I find abhorrent, and embrace what I love about it, and use it now.

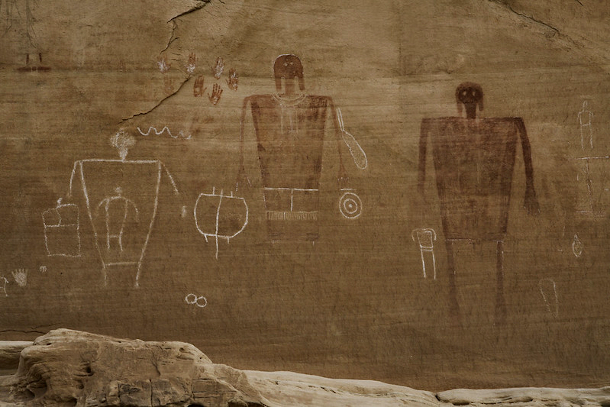

Native American rock art at Cedar Mesa, part of the original Bears Ears monument designation. (Photo: Bob Wick, BLM, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: Well, so what do you say to people who say, you know, those men, those white men, they had their time, they got to do a lot of talking while other people didn't get to do any of the talking. And you know, they, certainly they had their moment. Now let's forge a new path. And let's, let's listen to some new voices.

GESSNER: Well, I respond by saying, I partly agree with them. And I think that part of the interesting thing that happened in the course of the book was I wanted to learn about the Antiquities Act and about Roosevelt, and about the early environmental fight. But the book more and more focused on Bears Ears National Monument. And Bears Ears National Monument is the first national monument to be born from the thinking, the planning, and the hard work of five Native American tribes. And I interviewed Regina Lopez-Whiteskunk, who was one of the Mountain Ute tribe members for the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Council. And she said to me right away, we didn't want to relive, you know, historical trauma, we didn't want to say, it's our land, give it back. We wanted to use the tools of the United States to do something new. So she and the group studied the Antiquities Act. And they used that to create Bears Ears National Monument. And some of the things they included and that are included in the proposal, are the use of medicinal plants, are the use of the land for ritual, are the importance of the Native heritage. This was a land, this wasn't just common ground, now, it was common ground thousands of years ago for tribes that would meet and trade. So the exciting thing for me early on, was to take this old fairly sturdy vision of the natural world. You know, we call, Wallace Stegner called America's parks, "America's best idea." And maybe they weren't the best idea, but it was a pretty good idea. And to take that pretty good idea, and turn it in a new way, that includes inclusiveness, diversity, and a way of looking at the land not as a tourist, not as a user of the land, but as someone who belongs to the land. And to me, that was thrilling. And that changed the whole direction of the book. And one of the things I started to study was the history of taking land from Native people. An example would be the very first national monument, which we know as Devil's Tower, but was known to the native people there as Bears Lodge, and it had been sacred ground. So we saved that as a national monument, but before that, for hundreds of years, it was already the sacred special land belonging to the native peoples.

Devils Tower or Bear Lodge Butte in Wyoming was the first U.S. national monument, established on September 24, 1906 by President Roosevelt. It is considered sacred by Northern Plains Indians. (Photo: Tim Lumley, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: David, how does the movement to protect Bears Ears represent a new vision for conservation, do you think, in this country, and maybe beyond?

GESSNER: Well, one thing I love about the Bears Ears fight, is if you read the declaration of Bears Ears as a national monument, it reads like a bunch of nature writers got together. In fact, it was Indigenous people, and then politicians who got together. But you learn not just about the history of the place that's being saved. You learn about the phenology, you know, the phenomenon of the year, what grows when, what buds when, when the birds return. And by the time I finished reading the proclamation, I felt like, wow, these are people who get it, who get a different view of the world, not as selling and buying and power, but as a process that goes on cycling through the year and then through the years, and then through the centuries. And that place has such a deep history. I mean, the place is the embodiment of the Antiquities Act. The very first time I walked into that landscape, we hiked without seeing anyone for two miles. And all of a sudden, tucked into the sandstone ledge was a little village, and I always compare it to like a cliff swallow's dwelling, it was so organic to the place, you know, and it had been deserted for 600 years. And here we were looking up at it. And, to me, that's, you know, just such an exciting connection between the past and the present. To look back and to learn from what came before. And to, you know, to give the people that came before the credit they're due, while being critical of them where we should be.

DOERING: David Gessner is the author of Leave It As It Is: A Journey through Theodore Roosevelt's American Wilderness and teaches at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington. Thank you so much, David.

Moon House is one of numerous ancient cliff dwellings within Bears Ears National Monument (Photo: Bob Wick, BLM, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

GESSNER: Thank you, and I have to say as a way of goodbye, "Bully!"

DOERING: And there is “bully!” or “excellent” news for proponents of Bears Ears National Monument. On his first day in office, President Biden directed his Secretary of the Interior to consult with tribes and review the Trump Administration’s 85% reduction of Bears Ears.

Links

Read the Bears Ears Proclamation

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth