Searching for Life on Mars

Air Date: Week of February 26, 2021

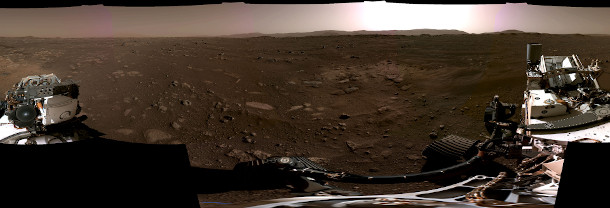

A panoramic view of Perseverance’s landing site on February 18, 2021. (Photo: NASA, Public Domain)

After a spaceflight of over 200 days, NASA’s Perseverance rover has landed safely on Mars. Perseverance is the first part of a three-phase mission designed to find signs of ancient life on the red planet, and return samples to Earth by the 2030s. Sarah Stewart Johnson, a planetary scientist at Georgetown University who has worked on the Opportunity, Spirit, and Curiosity rover missions, joins Host Steve Curwood for an update.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

After a spaceflight of over 200 days, the Perseverance rover landed safely on Mars on February 18th.

[SFX touch down confirmed, Perseverance safely on the surface of Mars ready to begin seeking the signs of past life. (cheering)]

CURWOOD: Venus is our closest planetary neighbor, but it’s a hothouse of nearly 900 degrees Fahrenheit and shrouded with clouds. Mars is much further away, but with a bit of atmosphere and morphology that suggests ancient rivers and oceans. So, NASA designed the Perseverance rover to search on the Red planet for signs of ancient microbial life, and perhaps help answer the enduring question of ‘are we alone in the universe?’ Perseverance touched down softly in an area that appears to have been at the edge of a Martian ocean, some three and a half billion years ago. Back when the robot launched we with spoke with astrobiologist Sarah Stewart Johnson. She worked on the Opportunity, Spirit, and Curiosity rovers and wrote the book The Sirens of Mars: Searching for Life on Another World. And she’s with us now for an update. Sarah, welcome back to Living on Earth!

JOHNSON: Steve, thanks so much for having me. It's a pleasure to be here.

CURWOOD: Now, the last time we talked to you, Perseverance hadn't even launched yet. So how did the launch and the flight and landing go for this mission? Of, course many of us saw on television, but from your perspective, as a professional in the business, how did it go?

JOHNSON: Oh, just spectacularly well, it was just flawless. I mean, the high definition video of the landing has now been released. And I really hope your viewers have a chance to watch it, it will blow their minds. You know, NASA sent this spacecraft on a journey that was 300 million miles. and Perseverance came blazing in to the top of the Martian atmosphere at 12,000 miles an hour. And over the course of seven minutes, what we like to call the seven minutes of terror, it slowed down to just two miles an hour, it landed perfectly unharmed, right next to this exquisitely preserved ancient River Delta, which is the main science target for the mission. And I guess that all just kind of speaks for itself,

CURWOOD: River delta? From how long ago?

JOHNSON: So, it's over three and a half billion years old, which is one of the most ancient times on Mars. And when we think back to our own ancient past, so much of that has been lost because of plate tectonics, because of fluid erosion. It's almost like we've swallowed our past plate by plate, we have so little left of that ancient history here. But on Mars, the past is everywhere. There are all of these incredibly old rocks. And this delta is from a period when we think that Mars was much more habitable than it is now.

CURWOOD: So this means we're gonna find life there, maybe? Kind of? Hoping? What are the odds?

JOHNSON: You know, I'd still say it's a bit of a long shot, but we're really hoping. So one thing to know about Mars is that, you know, Mars was a lot more similar to the earth around the time that life was getting started here. And so it's a big open question, you have the same sort of planet, the same types of starting materials, we found the building blocks of life, the organic molecules from which our own life is built. We found all the essential elements for life as we know it on the surface of Mars. We know that there were lakes and streams, maybe even a Great Northern ocean that existed on the planet early in its history. And so it's kind of an open question, did life you know, start twice? Did lightning strike that right over at the planet next door, or not? And so I think that that's why it's so exciting to look at Mars, because we've never found another planet, in the universe that's more similar to Earth. But still, you know, we have to, we have to do the hard work, we have to get these samples back to earth and really scour them with whatever we've got. You know, I like thinking back to this famous line that Carl Sagan once said, you know, extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.

Sample tubes, here being loaded into the Perseverance rover, are meant to house the samples of Mars as they are collected and returned to Earth. (Photo: NASA, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: So this is an extraordinary project that the Perseverance is a part of. Briefly, tell me, how are you going to get these samples back to Earth from Mars?

JOHNSON: So it's a great question. So what Perseverance is doing is kicking off this breathtakingly ambitious campaign to collect these samples of Mars and bring them back to Earth. And it's gonna take some time and some additional missions to actually get them back. So it's gonna be at least a decade. And the idea is that there will be three missions, you know, some of the details are still being worked out. But this first mission, Perseverance, will spend the next two years exploring this place called Jezero Crater. There are all kinds of exciting astrobiological targets that the rover will go up to and explore and characterize. And it will collect samples, at least 20 of them, hopefully double that number. But they're about the size of a piece of school chalk each, and it will cache those. And those samples will be left on the surface for the next mission to come along. And that mission will be a fetch rover that will pick up all of those samples and put them into an ascent vehicle, which will power on up to orbit. And then another mission will come and take those samples up from orbit and carry them home to Earth. And the best possible timeframe is we're looking at the 2030s to to get them back and of course it is just, it's an incredible undertaking. You know, you may have heard the term 'go big or go home'. You know, a lot of folks in the Mars community try to describe this as 'go big and go home'. But for the community of astrobiologists, I have to tell you, it's just incredibly exciting, the idea that one day, you know, I might be able to hold these various samples in my hands, you know, that we could get these back into our laboratories, these very carefully selected samples that we think might hold those echoes of ancient life. I mean, there just couldn't be anything better.

CURWOOD: So what could be in those samples to tell you about life? I mean, I gather we're talking about the fairly microscopic, or certainly small, forms of life.

JOHNSON: That's right, Steve. So it's really only been in this last chapter of our history here on Earth, that we've even had multicellular life, but microbial life, simple life, has dominated our own biosphere for most of our history. And that's the main thing that we're thinking we might find on Mars. And what we're looking for are called biosignatures, or traces of life, really anything that could denote a biological origin. And you've seen fossils before, you know, we didn't get body fossils here on Earth again till recently. But there's a molecular version of that, there are molecular fossils, where we can see with particular types of organic molecules, different chemical constituents that would potentially be very indicative of life. We could also potentially find biogenic minerals or structures, types of ancient microbial mats that might have been preserved in the lake that was in Jezero Crater. And the surface of Mars has become a pretty hostile place for life to exist, there's a really difficult radiation environment that life has to contend with. It's almost like a sterilization chamber right at the surface of Mars. And so we're really focused mostly on ancient life. And those samples, though, deeper down in the subsurface, that's a place where current life might actually still exist. And so that's one of the exciting things about another rover that's on the horizon, a mission from the European Space Agency, called the Rosalind Franklin rover, which is going to drill down through that thick basalt a couple meters into the subsurface, where you'd have a lot more protection from that dangerous radiation.

Now that you’ve seen Mars, hear it. Grab some headphones and listen to the first sounds captured by one of my microphones. ????https://t.co/JswvAWC2IP#CountdownToMars

— NASA's Perseverance Mars Rover (@NASAPersevere) February 22, 2021

CURWOOD: And so when does that land? And how far away from Perseverance will that activity be going on?

JOHNSON: So it's gonna land in 2023, in a place called Oxia Planum, and too far away, unfortunately for those rovers to rove toward each other and meet one day.

CURWOOD: What else is the Perseverance project doing? Aside from getting these samples near the spot where it is likely maybe there could be life forms or, or signatures of life forms, what else is the Perseverance project doing?

JOHNSON: So it's, it's sending the helicopters, that's one big part of it a technology demonstration. It's also doing some in-situ science as we explore the surface. And you've got to keep in mind, we've only touched down on a few spots on Mars, we just know so very little about what it's like to be on the surface. And so Perseverance is going to be exploring Jezero Crater trying to understand how it formed, what is its geologic history, what clues can be gleaned from that about the climate history of Mars, which is another big mystery for the Mars Science community. And it should be noted that the samples that will be returned to Earth will be studied from an astrobiological perspective, but they also may give us huge insights into the geochronology of Mars, the paleomagnetism of Mars, those are probably kind of big words, but really just understanding how old are these different rocks that were collected? And, and what sort of traces of the magnetic history can we glean? What point did Mars Stop being so habitable? And what point was the atmosphere lost to space, and Mars just kind of became the cold frigid desert that it is today?

CURWOOD: By the way, there were two other Mars missions happening around this launch. I'm thinking of the one from the United Arab Emirates called the Hope Orbiter. And there's one from China called what the Tianwen-1, what are some updates from those expeditions?

JOHNSON: It's been a banner month for Mars. You know, those two missions also arrived without a hitch. They went into orbit on February 9 and February 10. And it's just been terrific. They're starting to send back their own data. That Chinese mission is not just an orbiter. It also contains a rover and a lander. And so these other parts of the mission aren't going to get deployed right away. It's probably going to be May or June, before the Chinese orbiter has mapped enough of the terrain, figured out exactly where they want to land and put the, puts the lander down, and then the rover will come out and start exploring the surface of Mars.

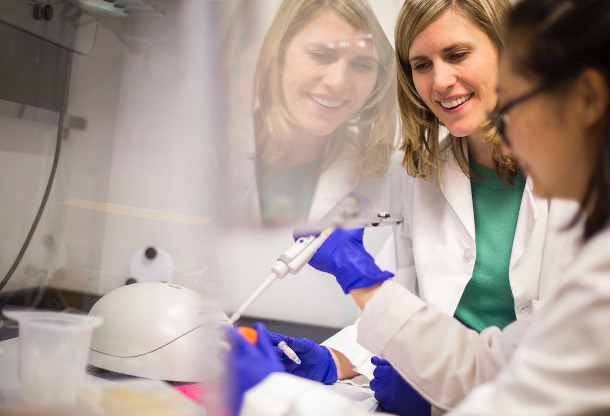

Perseverance is collecting samples of Mars to be studied by astrobiologists like Sarah Stewart Johnson, seen here in green and white. These samples may contain biosignatures, or indicators of life, whether that life is modern or ancient. (Photo: Courtesy of Sarah Stewart Johnson)

CURWOOD: To what extent is there hope in the interplanetary community, that China and the US can work together on these expeditions?

JOHNSON: I think there's a lot of hope, I'm not sure how it will happen. I think that the scientists are really longing to have more collaboration with the Chinese. From a scientific perspective, all of the data is good data. And it's all exciting to look at, and the Chinese are going to be exploring an entirely new part of Mars, the Chinese US relations have been challenging, I'd say, especially on the political level, but maybe we'll see some thawing in the months and years to come. We see a really different dynamic with the UAE, like that mission, you know, parts of it were built in the United States, there was so much back and forth between the engineers. And so I just am very hopeful that, you know, you could have a slightly more collaborative relationship going forward. And I think that my Chinese counterparts feel the same way.

CURWOOD: So, one of the bits of technology that came to light, especially during the pandemic, is that we can literally email a virus from one place to the other. In other words, describe the sequence and then somebody at the other end can replicate it. What equipment, if any, does the Perseverance have to take a bunch of observations that then could be sent back electronically to Earth so that we could duplicate the substances or configurations that it's discovered?

JOHNSON: That's an interesting question. So all of the data is coming back to earth through these orbital relays, there are these four different orbiters that are collecting data from Perseverance and then sending it back and a big data dump. But you know, this data is caught in these giant dishes here on Earth, and relayed to JPL into the science team, which is operating remotely. One thing that we have learned a great deal about are things like what is the particular mineralogy on Mars, or what are the, you know, weather conditions and, and some of that has fueled something I'm part of, which is called a planetary analog research. And whereas we're not always creating the same thing in the lab, like we do find places on earth with relevant similarities to Mars, and we can go do work in those environments, you know, we can learn how to look for life in those types of mineral constituents and see what works best. And so that's been great. The sample analysis at Mars, which is an instrument team that I'm working on with the Curiosity rover, there was what we have been calling the Cumberland analog, where we knew the precise mineral composition of a particular sample, that Curiosity collected and analyzed, and that was refashioned in the lab, you know, a little bit of this mineral, a little bit of this mineral, a little touch of this mineral, like an old recipe. And that Cumberland analog sample is sent off to many, many collaborators and different labs to run experiments, you know, to try to dope it with certain types of organic molecules and see if you could recover them all. All kinds of things.

CURWOOD: So Sarah, before you go, give us the big picture here. What What does this mission that Perseverance is in this first wave of, and for that matter, space exploration in general, what does it mean for humans here on earth?

Sarah Stewart Johnson is an astrobiologist and a Georgetown University Associate Professor who has worked with the NASA Science Teams for the Opportunity, Spirit, and Curiosity rovers. (Photo: Brittany Waddell)

JOHNSON: Well, I think it means different things to different people. But I can tell you what it means to me, at least you know, it, it may be a while, of course, before we get these samples back, and it's by no means guaranteed that we're gonna find what it is we're looking for. But this type of exploration, I feel like it's allowing us to ask fundamental questions about our place in the universe, you know, trying to really get at this idea of, are we alone? You know, why is there something and not nothing? And did that something from nothing, did it happen once or did it happen time and again, and I just think that the science involved there is just so compelling and so interesting, but especially right now, kind of in our current circumstances, I think there's another dimension here too, which is why exploration just kind of on its own is valuable. I think it'd be really hard not to like watch this feat of human ingenuity to watch that incredible landing to think about this idea that there's this machine that was built with human hands and we've sent it off to another world. I just, I feel like that really instills the sense of awe and an inspiration and, and I guess at times like these, it just can't be a bad thing to be reminded of what a civilization can do when we're working at our very best.

CURWOOD: Sarah Stewart Johnson is an associate professor at Georgetown University, and author of The Sirens of Mars: Searching for Life on Another World. Thanks for taking the time with us today.

JOHNSON: Oh, always a pleasure, Steve. Thanks again.

Links

Click here for more on NASA’s Mars 2020 mission, including the Perseverance rover

More on Sarah Stewart Johnson’s Biosignatures Lab

The Laboratory for Agnostic Biosignatures

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth