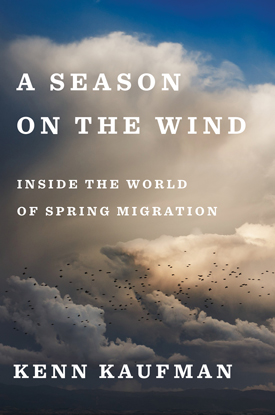

A Season on the Wind: Inside the World of Spring Migration

Air Date: Week of April 9, 2021

Many songbirds are known to make their migration during the nighttime hours. (Photo: Unsplash, Barth Bailey, Public Domain)

Every spring and fall, a journey of thousands of miles begins, as migrating birds find their way between breeding and overwintering grounds. It’s an incredible phenomenon that naturalist Kenn Kaufman brings to life in his book, A Season on the Wind: Inside the World of Spring Migration. Kaufman is the author of the Kaufman Field Guide series and is also a contributing field editor with the Audubon Society. He joined Host Steve Curwood to talk about his latest book and what our species can do to avoid harming birds on their remarkable journeys.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Kenn Kaufman is a renowned writer, artist and naturalist who has produced a variety of books focusing on the natural world, including the eight-part Kaufman Field Guide series. Since the age of six, Kenn has been a self-proclaimed bird nerd. He joins us today from northwest Ohio to talk about his 2019 book A Season on the Wind: Inside the World of Spring Migration. Thanks for being with us, Kenn!

KAUFMAN: Well, thanks, Steve. It's great to talk with you.

CURWOOD: Your new book is called "A Season on the Wind: Inside the World of Spring Migration." But you've written a bunch of them, how many guide books?

KAUFMAN: I've written about seven actual identification guides to nature. And, then a couple of books actually intended for reading.

CURWOOD: So we shouldn't read the guidebooks, huh?

KAUFMAN: Oh, well, a lot of people just look at the pictures!

CURWOOD: But, I bet little Kenn would have actually read it from cover to cover.

Kenn Kaufman’s new book A Season on the Wind: Inside the World of Spring Migration is available now. (Photo: Courtesy of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

KAUFMAN: (LAUGHS) I would have, yes. The guide books that I did have I did read cover to cover. I had memorized books by Roger Tory Peterson by the time I was 10 years old.

CURWOOD: What prompts, a kid really, to have practically memorized a field guide to the birds by Roger Tory Peterson.

KAUFMAN: Well, I was just so fascinated with birds as a little kid. I mean, I, I sort of discovered birds when I was about six. And, when you look at things like robins or grackles out on the lawn, and you get close to them, which you know, as a kid, you could just crawl across the lawn. Nobody thinks anything of it. Those birds are just so intense. They are so intensely alive, that I was just captivated by looking at them. And, so, I've just been utterly fascinated with birds and then with other aspects of nature, ever since I was six or seven years old.

CURWOOD: So, last time we spoke you were in Arizona, why are you in Ohio?

KAUFMAN: Well, I mean, Arizona is great for natural history in general. And there are a lot of birds there. But bird migration is not so obvious there as it is in eastern North America. There's just more birds that pass through the eastern half of the United States. And this area, Northwestern Ohio, the edge of Lake Erie, is really a fabulous concentration point for migratory birds.

CURWOOD: Well, how do you see them? Because as you write, the songbirds migrate principally at night.

Warblers are the most popular of the migratory songbirds that mark the peak of spring migration. The Blackburnian Warbler spends the winter in the Andes in South America, migrates north in spring through Central America, across the Gulf of Mexico, through the eastern U.S., heading for breeding grounds that are mostly in the spruce forests of Canada. (Photo: Courtesy of Kenn Kaufman)

KAUFMAN: That's right! So, it's sort of this massive phenomenon that's largely invisible. And, that's that's part of what makes it interesting. But here, birds are coming north on a broad front across eastern North America, they come North across Ohio, they get close to the edge of Lake Erie, and if it's approaching dawn, they can see that there's water ahead. And these birds will just come down and then land and so the numbers pile up on the edge of Lake Erie, the little wood lights there. On a good morning, after a good night, those woods are just full of these small songbirds. They concentrate there, and often they'll stay for several days feeding and fattening up for the next flight.

CURWOOD: Now, there's a term that's often thrown around where birds go during migration called flyways. But you write that flyways are a dated concept, why?

KAUFMAN: It's an interesting concept. The idea of bird flyways was developed first by people who were studying duck migration. And it was easy to study duck migration, because you can catch a bunch of them at once at some water area and put bands on their legs and then later ask the hunting community to send in the duck bands from the ducks they've shot. You very quickly can get a sense of where a lot of these birds have gone. And ducks do sort of follow specific flyways from one water area to another. But the great majority of birds don't follow anything like that. If you could look down on North America from outer space on a night at the peak of migration to see where the birds were going, you wouldn't see rivers of birds flowing toward the north. It would look more like a blanket of birds being pulled northward.

CURWOOD: And, yet, you write that people often come at the spring migration time to where you live there in Northwest Ohio. So if it's not a flyway, why do people come from all over the world to watch the migratory birds in your neighborhood?

KAUFMAN: They come there, because of the sheer concentrations of birds. The birds are moving north on a broad front. So, there would be just as many individuals passing over an area, say 150 miles farther west. But in this area, they're pausing because they're coming up to the edge of Lake Erie. And, we also have a lot of really good habitat here. So, birders can spend all day, or spend all week, going from one wood lot to another, or going to the marshes, going to the fields. And every place they go, they'll see concentrations of these migratory birds that are stopping over.

CURWOOD: By the way, what about the fall migration?

In the summer the Eastern Kingbird live in the eastern two-thirds of the U.S. and southern Canada, feeding on insects in open country. In winter, they gather in flocks in the Amazon rainforest, feeding on small fruits in the treetops. Talk about a double life. (Photo: Courtesy of Kenn Kaufman)

KAUFMAN: Well, fall migration is exciting. Actually, for the, the really serious birders they're often more excited about fall migration. There are more birds then. The total population is higher because the birds have been hatching young all summer. So you have all these young birds migrating south for the first time. So, the numbers are higher, and the young birds are more likely to wander out of range. So you'll get more rare birds, more things in places where they shouldn't be, during the fall. So, it's a very exciting time for birding. But to me, the thing about spring is that it's just a sense of resurrection, almost. A sense of rebirth. Especially if you're in northern Ohio, and things have been frozen solid all winter, and things start to thaw out. And all these birds come back. It's just such a, such a wonderful feeling that I can't help just wanting to go out and celebrate.

CURWOOD: Let's just say that one of the spring mornings, I'm with you there near the coast of Lake Erie. Springtime migration is happening. What does it sound like? What does it look like?

KAUFMAN: It's just a fabulous experience, if you can be out there at dawn or just before first light, along the edge of Lake Erie because you hear the night sounds, of course, there are the frogs and insects and there are a few night birds, like screech owls that are calling. But, then you hear the sounds of these birds. A lot of these nocturnal migrants are calling in flight, doing these little chip notes, little buzzes and things. And you hear more and more of that as the birds come lower. And some of them are coming in from the south and landing in the trees. But then as it starts to get light, you look out and there's small birds sort of flying along, paralleling the edge of the lake. There are others that are actually coming in from the north. Because, when these birds are migrating, if they're out over the open water when it gets light, they'll actually climb up somewhat higher and look around. We know this now from radar studies, right at dawn, we have birds arriving from all direction. Some are just pitching into the trees, some are flying along, paralleling the shore of the lake. And it's just an amazing amount of movement. It's just, it's like the whole world is alive with this movement of birds.

CURWOOD: How do they know where to go?

KAUFMAN: You know, that's a question that people have been working on for a long time. It's an amazing instinct that these migratory birds have. There are some kinds of birds that actually learn their migratory routes. Some things like cranes, for example, or swans or geese, the young birds just follow along with their parents and learn the route. So it's a tradition thing, not so much an instinct. But on the other hand, most of the small migratory birds, they're just going on instinct. And you can just leave a warbler, just drop it off in the north woods, and it will find its way from northern Alberta, perhaps, down to Brazil, without any guidance, without anyone showing it where to go. It's amazing that they've got this instinct. And then a lot of these small birds that migrate at night, they can navigate by the stars, they can detect the Earth's magnetic field. A lot of them can hear very low-pitched sounds, so they can hear, like, the sound of waves crashing on the beach from many miles away. We're still figuring out and still learning some of the things they use, but the navigational abilities of these birds are extraordinary.

CURWOOD: And yet we use the phrase birdbrain.

KAUFMAN: (LAUGHS) Yeah, I think birdbrain should be considered a compliment.

The Blackpoll Warbler is an extreme migrant among the warbler family, nesting across Canada and Alaska, wintering east of the Andes in South America. (Photo: Courtesy of Kenn Kaufman)

CURWOOD: So, in your book, you mentioned that birding is now seeming to become a more welcoming and diverse hobby. Talk to me a bit about that, and why you think that may be.

KAUFMAN: When I was a kid, birding was mostly a hobby for really well to do, you know, older white people. And even just as being a kid, I was sort of an oddity. And I once I wrote some books about birds in nature, and I started traveling around the country, speaking to bird clubs and things, it was really disturbing to me to see that I could go to some place where I knew that there was a very diverse local population, but I'd look out at the audience and just see a sea of white faces. And these people were all, you know, they were all perfectly nice, but I was just thinking about people who are not there. But now there are a lot of people who are starting to break down the stereotypes and the old barriers. And so when I go out in my local area on the boardwalk Magee Marsh to look at the migrating warblers in spring, I see a really diverse crowd. They're getting more and more families coming in. There are more people of color, there are people from other countries and other continents coming there. We're seeing lots of young people and every birdwatcher knows that diversity is good. You know, you want to go out and see lots of kinds of birds. You want to go out and see lots of kinds of people looking at birds. So to me, this is the best thing about what's happened in recent years.

CURWOOD: Kenn, what are some of the top locations here in North America that you suggest for migration birdwatching?

KAUFMAN: Some of the areas that are really outstanding in spring include the upper Texas coast, going over into Southwestern Louisiana. Just amazing numbers of breeds that stop off there in certain conditions in spring. There are places out on the Great Plains that are wonderful for shorebirds, some of the wetland areas in Kansas, for example, Cheyenne Bottoms and Quivira refuge in Kansas sometimes have amazing numbers of sandpipers that have come from South America and are headed to the Arctic. There are places in Florida, the Dry Tortugas off the end of the Florida Keys, wonderful area for migratory birds. And then when you turn it around and start looking in fall, there's a different set of places so that, for example, Cape May, New Jersey is one of the best places in the world to see migratory birds in fall. The area of Duluth, Minnesota right at the western end of Lake Superior is a fabulous place for fall migration.

CURWOOD: By the way, what have you observed in terms of climate change affecting bird migration?

KAUFMAN: I don't know any bird people who deny the reality of climate change, the fact that it's happening, and we're starting to see how it has an impact on birds. There are quite a few areas now where there are long term studies where we know that the birds are arriving earlier in spring. Arriving on average, like five to 10 days earlier. And in some cases, that puts them in difficult situations, because in some places, the birds are coming back a few days earlier, but the trees are leafing out much earlier than they used to. So the peak of insect populations now may be happening earlier in the season. And the birds are not in sync with it the way they would have been at one time. And I think we're still in early stages of it, and still in early stages of the studies. But I think we're going to see more and more impacts of climate change on these migratory birds.

CURWOOD: May be climate change, it may be chemicals, it's unclear, but there does seem to be a mass insect collapse going on. How do you think this is affecting the migrations for that matter, the whole business of being a bird?

KAUFMAN: Well, certainly a decline in inside populations is bad for birds, the majority of bird species in the world do feed on insects. So they're like the basic main item on the menu. One thing that's been determined recently is that, for birds that are wintering in the Caribbean, for example, there are long term studies in Jamaica, they found that if it's a really dry, warm winter, and insect populations are low, some of the migratory birds leave later in spring. You would think they would leave earlier just wanting to get out of dodge, because there's not much food. But apparently it takes them longer to build up fat reserves that they need. And that puts them at a disadvantage when they get to the breeding grounds. But this kind of thing is likely to happen all over the place. So decline in insect populations is going to be bad for birds across the board.

CURWOOD: Now, one of the more interesting illustrations in your book is a picture of a billboard that you bought of warning of the dangers of wind turbines. What's your concern?

Kenn Kaufman encourages thoughtful planning on the placement of wind turbines in his book. (Photo: Courtesy of Kenn Kaufman)

KAUFMAN: Well, I have to say, I'm not opposed to wind power, I don't think it's a bad thing. I think wind power is a really important source of renewable energy. And it's really worth developing, I just think the location is important. If you put up a wind turbine, any place, it's likely to kill a few birds. And that's just the way it goes. We can't take all the things threats to birds out of the environment. And it's so important to have green energy that, you know, we'll accept the fact that there's going to be some mortality of birds with these big spinning blades. But there's some places where wind turbines are going to kill so many birds that it's just not worth the risk. And one of the types of places where wind power is really a problem is in this major stop over habitat for birds. Like where we are on the shore of Lake Erie, there are all these nocturnal migrants coming in. They're landing in the dim light just before dawn, they're taking off in the dimness, just after it gets dark. And so they'd be going right through the sweep of these rotor blades on the wind turbines. Whereas a wind turbine out in the middle of farm country someplace, might not really be that damaging for bird life. Here on the lakeshore, in the middle of this stop over habitat, it could really do serious damage to populations of these long distance migrants that are already facing so many threats.

CURWOOD: For those people who live at a stop for birds on their migratory path, what can they do to make their local environments more welcoming and helpful to these traveling birds? Keep your cats inside, grow native plants, eliminate or at least reduce the use of chemical pesticides? And anything else, Kenn?

KAUFMAN: I really appreciate that question because that's something that's relevant everywhere. Just supporting conservation efforts in general, supporting protection of native habitats. There are cases where just by voting on certain issues, people can affect what happens with wildlife habitat in their local area. It's worthwhile for people to educate themselves about the issues and pay attention to what policy changes are going to have an impact on bird life.

Kenn Kaufman is a renowned birder and naturalist (Photo: Courtesy of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

CURWOOD: Before we go, what do you hope readers will come away with after reading your book?

KAUFMAN: I'm hoping that people who read the book will learn something about the science of migration. But if I, if people were to come away with one thing from it, I hope they would just be taken with just the sense of wonder. Just the fact that this is an amazing, miraculous thing that we're seeing. And it, it happens everywhere. So it's a true miracle that happens twice a year, and that you can witness just about everywhere. And I think the more you learn about it the more magical it becomes. And, so, just the blend of science and magic is the one thing that I hope that people will take away from the book.

CURWOOD: Kenn Kaufman's book is called "A Season on the Wind: Inside the World of Spring Migration." Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

KAUFMAN: Well, thanks, Steve. It's always great to talk with you

Links

Kenn Kaufman’s Official Twitter

Audubon | “Kenn Kaufman's Backyard Is One of the Best Spots to Witness Spring Migration”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth