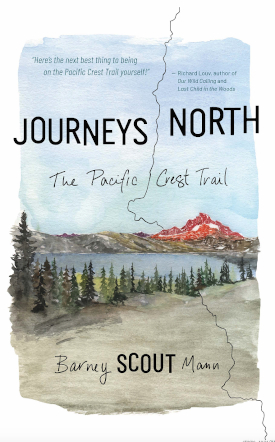

Journeys North: The Pacific Crest Trail

Air Date: Week of August 13, 2021

The Pacific Crest Trail runs 2,650 miles from the U.S. border with Mexico to the Canadian border. (Photo: Bureau of Land Management Oregon and Washington, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

In a typical year, several hundred intrepid hikers walk all the way from Mexico to Canada, along the Pacific Crest Trail. At more than twenty-six hundred miles long, it covers some of the most challenging and spectacular terrain in North America. But it’s not just about the pretty scenery, writes Barney Scout Mann in his book Journeys North: The Pacific Crest Trail. He joins Host Bobby Bascomb to talk about braving blizzards, bears and blisters, and the tight-knit community he and his wife Sandy found on their PCT hike.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth I’m Steve Curwood.

In a typical year, several hundred intrepid hikers walk all the way from Mexico to Canada, along the Pacific Crest Trail. At more than twenty-six hundred miles long, it covers some of the most challenging and spectacular terrain in North America. But it's not just about the pretty scenery. In his book Journeys North: The Pacific Crest Trail author Barney Scout Mann writes about the tight-knit community he and his wife Sandy found when they hiked the PCT. He spoke with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb

The cover artwork of Journeys North by Obi Kaufmann depicts Thousand Island Lake and Banner Peak, notable sights on the PCT as it traverses the Sierra Nevada range. (Image: Courtesy of Barney Scout Mann)

BASCOMB: So what drew you and your wife Sandy to hike the trail back in 2007?

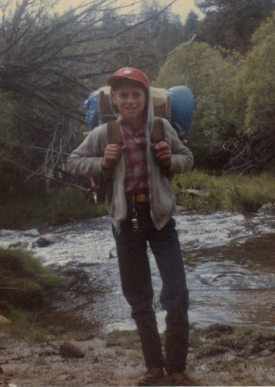

MANN: So you have to go a ways back. Both of us fell in love with backpacking at about the same age. I was 13 years old. And I was born into a household with parents who don't camp. But they took me at age 11, 12, 13 to Boy Scout meetings. And there at age 13, I went on a 50 mile backpack in the Sierra Nevada, John Muir's "Range of Light." I was, always been the smallest boy in any class at school, which is hard on a boy. It's no fun, I had to dance as fast as I could to make sure I wasn't the kid picked on, and it didn't always work. But out there, I saw stuff that I'd only seen on a TV screen, I grew up in Los Angeles. And so bears were not behind bars, I actually could see one. And hearing a beavertail slap in a stream, and seeing it. This was the real deal.

And the other thing was, out there, as long as I walked, and alright, I did have a 35-pound pack on a not-80-pound body, and that was hard, it was! But out there, as long as I kept up, I was the same as the big boys. So at age 13, I fell in love with backpacking. And for Sandy the same. My wife, Sandy, who has the trail name Frodo, and actually Scout is not my given name, but to thousands of people they only know us as Scout and her trail name, Frodo. She too, she'd see her brothers go off too on Boy Scout campouts, she'd think, I can hike! I want to do that. And it wasn't till later as a teen she got a chance.

Barney Scout Mann on his first 50-mile backpack in the Sierra Nevada in 1965, at the age of 13. (Photo: Courtesy of Barney Scout Mann)

And as she said, when we met a few years later, if I hadn't been a backpacker, she wouldn't have married me. In 2003, we'd already begun thinking seriously about doing a thru hike, as they call it, doing the entire Pacific Crest Trail. And we went out on the John Muir Trail, which is "only" -- and we use the word "only" very strangely in this community -- only 211 miles. We wanted to see if we'd come off that still being as enthused about doing a thru hike. And obviously we did, because in 2007, the summer of our 30th wedding anniversary, we set out to hike the Pacific Crest Trail.

BASCOMB: Mmm, wonderful. Well, let's get a lay of the land here. You start your trip from San Diego, you make your way down to the Mexico border, and then walk all the way up to Canada. How does the landscape change as the PCT makes its way from each border?

MANN: Well, there's both a micro and a macro answer. The macro is, it changes dramatically. You have some landscape that is out of Lawrence of Arabia, sand dunes, it's one day in the Mojave and you have some of it. And you have landscape that is, you are above treeline, it is barren, it is white granite that glitters in alpenglow. And you have everything in between. I saw one guidebook that identified 15 different plant and fauna zones, and the PCT goes through all of them.

Scout and Frodo at the Southern Terminus of the PCT, steps from the U.S.-Mexico border east of San Diego, California. (Photo: Courtesy of Barney Scout Mann)

But you might think, okay, I'll be walking and one day, I'll be in one thing, and then it'll slowly and gradually change. And it doesn't happen at all. The micro scale, literally in a half day's time, I can go through, easily, and many times, go through half of those different flora and fauna zones. I cross under a dirt underpass under Interstate 10, east from Los Angeles, at about 1800 feet, and I'm in what looks to you like desert. And within, okay, not a half day, but two-thirds of a day, I have climbed up into a pine forest and have gone through all the zones in between: the different desert zones; oaken. And the other thing, it's not just the landscape changing. Because we're out for five months, we're walking through seasons.

Every night on the trail, Scout would look up in the sky and spot the Big Dipper, follow it to the North Star, and just think for a moment: “That’s the way I’m heading. That’s what I’m doing.” (Photo: Patrick Beggan)

I see a plant, and actually, each of my three long hikes, I've done the Pacific Crest Trail, the Continental Divide Trail and the Appalachian Trail. Each one, there's a plant called skunk cabbage, or false hellebore. Each one of these trails, I would see it sprouting in the spring, just the little tiny tips coming up, almost like a bulb. It's only about a foot and a half tall, really thick, lush green, and it has little flowers. And I know I'm reaching the end of my hike, because at the first frost, a bit like a tomato plant, the plant just collapses. And it's like a starfish on the ground. And I know it's, my hike is beginning to end when I've seen that.

BASCOMB: Well let's talk a bit about the culture of these long hikes, starting with the idea of trail names. That's a nickname that's given to you by your fellow hikers. How did you get yours? And how did Sandy come to be known as Frodo?

MANN: So imagine if you got dropped down into a completely different place. If you woke up one morning and you were in Hogwarts, or you woke up and you were in Narnia, would you still want to be Bobby?

BASCOMB: Mmm, that sounds a little boring! [LAUGHS]

Frodo carefully crosses a stream in Oregon on a log bridge. (Photo: Barney Scout Mann)

MANN: This is actually a tradition that started on the Appalachian Trail. You do something stupid, maybe it's a play on your name. But trail names are usually given, sometimes thrust on you, rather than something you choose, although that happens on occasion. A guy who was named "Sky God" as his trail name, didn't take too long to realize that he had chosen that name for himself. [LAUGHS] The name Scout dates back to our 2003 John Muir Trail hike.

First day out, a young man attached himself to us like glue. Twelve miles later, we're climbing up Half Dome, and he was just out of high school, the two of us must have looked like parental types, and I hear this question behind me. And the question is, "What's the most important thing you've done in your life?" And at that point, I probably had three, four, five truthful answers to that. But the one that came out of my mouth was, "I was Scoutmaster of a large Boy Scout troop for five years." And "Scoutmaster" is a bit pretentious, and the book that we'd torn up -- and yes, we used to tear up books and put 150 pages at a time in our resupply up the trail so we wouldn't have to carry the whole book that time.

But the book we'd done that to, and that we were reading was To Kill a Mockingbird. And who would not want to be named after nine-year-old Scout Finch? Frodo -- I hope we have some LOTR, some Lord of the Rings fans out there. Frodo comes from, it's my fault. About a year before we hiked in 2007, I woke up and realized, oh my gosh, that's going to be the summer of our 30th wedding anniversary! She's not a jewelry person, but I really wanted to do something special. So literally, the idea sprang into my head, whole cloth. I could see a Pacific Crest Trail ring, a custom ring. And you could look at it from four or five feet away and you'd see the trail symbol, that "pregnant triangle", as we call it, with the tree in the center and the mountains backdrop.

The PCT ring that Scout gave to Sandy as they set out on the Pacific Crest Trail the year of their 30th wedding anniversary, earning her the trail name “Frodo”. (Photo: Courtesy of Barney Scout Mann)

And in the channel would be a small outline of the northern and southern monuments, and of the two primary mountains that you see on the trail, Mount Shasta and Mount Hood. I drove a jeweler crazy for about six months, but she actually did it! I give her the ring. We both cry. And if she was here, she'd say, Yeah, you cried more, which is true. I did! [LAUGHS] And the next day, we'd had a number of hikers who I had shown before I gave it to her, and all but as a group, they accosted her: "We want to see, show us the ring!" They said, "We know your trail name! You are the ring bearer. You're going on a long quest, a dangerous journey. You are Frodo!" And to this day, 13 years later, literally thousands of people, if not tens of thousands, know her simply as Frodo. And on her hand, she still wears the One Ring.

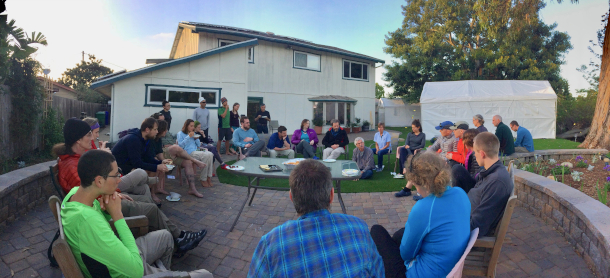

BASCOMB: Ah, lovely. And there are also people that are called trail angels. You and Frodo became known as trail angels for hosting people in your home. Can you tell us about that, please?

MANN: So you start with trail magic. And trail magic is literally any act of kindness toward a hiker, whether you pick up a hitchhiking hiker, whether you have a bit of your town lunch leftover, you've gone out on a day hike, and you run into a longer distance hiker, and you see them eyeing that piece of pizza you're just planning on taking home and throwing away, and you give it to them, and you've just made their day. That's trail magic. And you, who have done that, is a trail angel.

Scout and Frodo host an after-dinner talk with thru hikers, a few of the many thousands of hikers they have hosted over the years, about making the most of their PCT experience. (Photo: Courtesy of Barney Scout Mann)

And it goes from small to large. What we do is probably a bit large and maybe even obsessive. [LAUGHS] For about two months, we host hikers in our home. People from all over, about a third are internationals, and we'll have 30 to 40 hikers here a night, and we have this corps of volunteers, because it's all free. We had so much kindness in 2007 that came our way. You know, when we're out there in the small towns, we don't have the things we usually have at our disposal, and so many times and places along the way, we had trail magic, from trail angels. To be able to give back is, is great.

BASCOMB: That seems like something that's so rare in your day to day life, both A, relying on the kindness of strangers and having that appreciation for your fellow people and feeling like you want to give back to them, people that have been so generous with you.

Barney Scout Mann is also a trail advocate who is currently serving as President of the Partnership for the National Trails System. (Photo: Patrick Beggan)

MANN: That's one of the things I love about the outdoors. It's one of the reasons I wrote the book too, so people who, their comfort zone is their couch, they can have a moment to experience what it's really like to be out there. And one of the neat things, as my wife likes to say, she thought the hike was gonna be so much about the landscape and stunning views, the pain and deprivation and trying, you know, the physical challenge. But at the end of the day, what it was really about -- gosh, I'm going to tear up a little bit! -- it was about the people. If you and I were coming at each other on a trail, and whether we're out there overnight, a week or, you know, in my case, five months, I would look at you from afar, a couple hundred yards away and say, "oh, there's another person!" I would think, "this person would give me the shirt off their back." And I would anticipate you would have the same thought in your mind, that the default attitude is we're kind to each other out there. I tell people that out there, on the trail, I found the community of people I've always wanted to be with, and I never knew existed.

BASCOMB: Is that what keeps you coming back to these long trail hikes that you do?

MANN: Why do I come back to it? A lot of reasons, a lot of reasons. One of which, of course, is that rich, rich sense of camaraderie. The other is -- well, the best way to explain it is, our hike of the Pacific Crest Trail is 13 years ago. And today, as I'm talking, I'm 69 years old. I was out there for 155 days. And Bobby, today, right now, I could sit here and tell you a story for each and every one of those 155 days. We are open out there in an entirely different way. We imprint differently. And around any bend, at any moment, a small miracle can happen.

BASCOMB: So you have this great story in your book about a big bear that you encountered on the trail one day. Can you tell us that story, please?

MANN: [LAUGHS] Yeah, I love it! Although it doesn't necessarily put me in the best light!

BASCOMB: Well . . . [LAUGHS]

MANN: So we are a thousand miles up the trail. We are actually just west of Lake Tahoe. And people we've leapfrogged with, that's, you'll see for a couple days, and you won't see for a week, or you might have a break with, and then see them the next day. They've all seen a bear! Not only that, they have their pictures, and they have their bear stories. And we have not seen a bear yet. What's wrong with us? And it's not that we haven't on many other earlier trips. But we don't have our Pacific Crest Trail bear story yet. And we've gone through the country where it's most likely, in the Sierra Nevada. So my wife and I are camping alone, which we did just over the majority of the time. And we were cowboy camping, which means not a tent, it was nice enough, and we enjoy that, to camp under the stars. We would trade off every night, one of us would do dinner and the other of us would set up our little campsite. So that's what I'm doing. I'm laying out our sleeping bags, my wife is about 20 feet away. And on the other side of her, about 50 feet away, I see pull around this large rock, the largest black bear I have seen in the wild.

Beautiful specimen, height of summer, sleek coat -- actually cinnamon colored, as black bears can be. And as I like to say, this thing was the size of a small Volkswagen. And I can tell, as I see him, I can tell by his aspect, where he's looking, he is not aware of us yet. The wind direction is such, and he's looking away. So what's my first move? Hmm. There's me, between me and the bear is my wife, right? My first move is a quick, hand down, camera up, and I get off two shots. [LAUGHS]

A black bear “the size of a small Volkswagen” approaches as Frodo cooks dinner. (Photo: Barney Scout Mann)

But all the way I'm watching him! And then I get her attention, I go, "fftt!", just make a little noise. She looks at me and I flick my head and she looks, sees the bear. And she takes the pot of food, puts it in our bear canister, cranks down the lid, comes over, stands by me. And she says "what do we do?" She knows: what you want to do is look large, and show them you're human. And I guess a lot of people think banging on pots means that we're human because that's what people can do, or clicking your hiking poles together. But what we did was we sang, in two-part harmony, Leonard Cohen's "Hallelujah" to the bear. And as we reach the chorus, he turns his massive head and looks at us, long enough for us to know and acknowledge whose house we are truly in. And then he turns and slowly ambles away.

Scout and Frodo, a.k.a. Barney and Sandy, backpacking in 1977, the summer they were married. (Photo: Courtesy of Barney Scout Mann)

BASCOMB: So after walking some 2600 miles, you're just a few dozen miles from the border with Canada, from completing this entire hike that you've been doing, when a series of powerful snow storms dump just several feet of snow on the Cascade Range in Washington where you were hiking. What was it like to face that final test when you were so close from finishing?

MANN: Oh! We thought we had this in the bag. And at that point, this is now late September. At that point, you feel like you're in a vise. The days are growing shorter, so I have less time to walk. I see it all around me. I see it in the colors. I see the huckleberries are now gone and they're bright red. I feel it in the weather. And I feel it miserably at times in the weather. And you feel it in your body. I've been charging for now close to five months, and I'm getting messages from lots of different parts! And it's not just me, it's the young ones, too. We're being, we feel it. It's time to shut down. And we know, you can also feel, we have Canada in the bag! It's almost every year safe to finish by October 15th, I've seen people even finish October 31st. Because the snows at some point, shut down the trail. September 29, we are 60 miles from the Canadian border. We need three days and two nights. Unbeknownst to us, as you just said, a series of storms have lined up out of the Gulf of Alaska. And that night the first one hits.

I remember waking up and seeing the first snowfall: "Oh, this is sort of, you know, this is sort of cool!" And then as it starts to weigh down on the tent and you have to knock it off. And then it's, we're waking up to three, four inches already in the ground. And what's this going to be like? How much more is it going to go? And that day, we fairly quickly have a high pass. We're climbing first thing two thousand feet. We have a young woman, Blazer, one of the main other folks in the book Journeys North, we were close enough that she would call us her trail parents, her trail mom and trail dad, we'd call her our trail daughter. And Blazer, her, her jacket zipper's broken and she's lost a glove. I have, I have taught snowshoe backpacking. I'm experienced in snow backpacking. And as we get toward the crest of Cutthroat Pass -- what a name, huh! -- snow's been getting worse and worse, it's now over our ankles, and trail finding is an issue. This is days before anyone routinely carried a GPS or you had one on your phone. We have paper maps. And we see four people we know: Guts, Chuck Wagon, Dalton and Chigger. Do you love those trail names?

Frodo hikes in thick snow just 50 miles from the northern end of the PCT. (Photo: Courtesy of Barney Scout Mann)

BASCOMB: [LAUGHS] I do! Chuck Wagon, that's great.

MANN: Three guys and a gal, Chigger was a gal. They're heading toward us! Why are they heading toward us, this is wrong! And they say, "We have just turned around. The trail has become impossible to find. We're heading back to a road head. It's the last paved road, five miles back down at the base, and we're gonna hitch into the little tiny town Winthrop and see what the story is." We stand there in snow that's almost whiteout, and it's getting deeper by the moment. And for 10 minutes, I talk. Weighing it over; and, reluctantly I said, "Okay, maybe that is the best thing." And I turn and I take one step, South. I who have been heading north for five months. And I stop in my tracks. I can't go South. And I open my mouth. And I start to talk again. In the meantime, Blazer said I'm doing whatever Scout and Frodo are doing, and we felt likely the group would do the same. My wife and I had a tacit agreement. She did something that, as I'm talking there in the snow, it's the only time that she's ever done in our marriage. We've now been married 43 years. After about two minutes of me jawing again, she says "Scout, I'm exercising my veto. We're going back." I stop, stop talking. And we started heading down. And that was the first time [LAUGHS] we retreated from the snow!

BASCOMB: But you did finish eventually. You made it to Canada.

MANN: Yes, I'm still here. And we did make it to Canada that year, yeah.

BASCOMB: [LAUGHS] Yeah, I imagine; you make it sound like, you know, the geese that are flying South for the winter. They can't turn around and go North. That's just against what's ingrained in you at that point.

MANN: Yeah, yeah, there was this intense drive. Every night I'd go out and I'd brush my teeth. And on the Pacific Crest Trail, most nights were clear. And I'd look up in the sky and I'd spot the Big Dipper. And then I'd go from those two sides of the pot and I'd go six lengths out and I'd eyeball the North Star. And I'd just think for a moment. That's the way I'm heading. That's what I'm doing.

Despite three blockbuster snowstorms in the last miles of their hike, Scout and Frodo (pictured at far right), “trail daughter” Blazer, and the rest of their trail family did, eventually, make it to the border with Canada. (Photo: Courtesy of Barney Scout Mann)

CURWOOD: Scout Mann’s book is Journey’s North: The Pacific Crest Trail. He spoke with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth