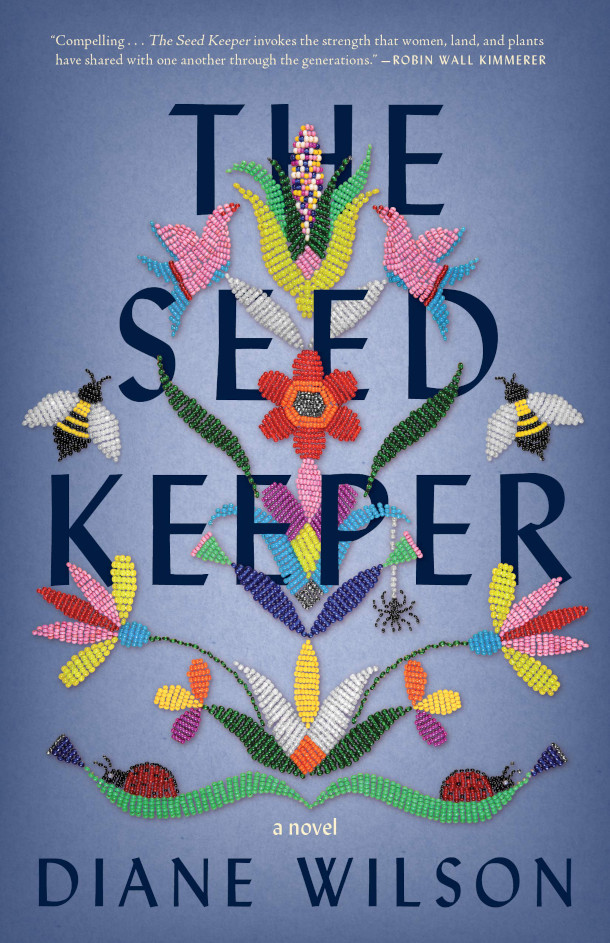

The Seed Keeper

Air Date: Week of November 19, 2021

The Seed Keeper is the newest novel from author Diane Wilson. (Photo: Courtesy of Diane Wilson)

For many Native American communities, seeds are living and life-giving organisms which should be carefully kept and cherished. But because of industrial agriculture and monocropping, more than 90% of our seed varieties have disappeared in the last century. The Seed Keeper is a novel that relays the importance of seed keeping across 4 generations of Dakota women who have experienced austerity and discrimination through war and American Indian residential schools. Diane Wilson is an award-winning author and the Executive Director for the Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance and she joined Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss The Seed Keeper.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb

This harvest season is a time when many of us turn to native American foods to give thanks. Afterall, for many, what is Thanksgiving without potatoes, green beans and pumpkin pie? The seeds for so many of our favorite foods of the season have been passed down through generations of Native American women. That tradition of keeping seeds is the backdrop for Diane Wilson’s novel, The Seed Keeper. A work of historical fiction, Diane tells the tale of 4 generations of Dakota women who, despite the hardships of forced displacement, residential schools, and war still managed to save the life giving seeds of their people and pass them on to their daughters. When Diane Wilson is not winning awards as a novelist, she is also the Executive Director for the Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance. And she joins me now. Welcome to Living on Earth Diane!

WILSON: Glad to be here.

BASCOMB: So Diane, what inspired you to write this book?

WILSON; Oh, well that's one of my favorite questions. You know, getting to relive the moment where these ideas come to you, even though I think it really grew over a few years. But there was a moment in about 2002 when I was participating in an event called The Dakota Commemorative March, and that was a biannual event to just honor and remember the 1,700, Dakota men, women, children and elders who were removed from the state after the 1862 Dakota War. So on this long walk, which was about 150 miles, somebody told me a story about the women who were preparing to be removed from the state and how they didn't know where they were going to be sent. They didn't know how they were going to feed their families, they didn't know what they were going to be able to grow. And so what they did was sow the seeds that they had gathered each summer in the hands of their skirts and they hid them in the pockets. And so that way, no matter what happened, they would have these seeds wherever they ended up. It was actually that story that stuck with me, that act of just fierce courage and protection for seeds. And it was it was a reminder to me of our responsibility to take care of these seeds and that when we do when we show that kind of commitment to them that they also take care of us. So it was that story combined with working at nonprofits doing similar work around seeds, protecting them and growing them out for communities that they came together in a novel.

BASCOMB: Now, the protagonist of your story is Rosalie Iron Wing, and she loses her father when she's young and basically grows up in the foster care system. But she eventually marries a white farmer. And there's a scene in your story where their farmhouse catches fire. And Rosalie's his first instinct is to save a box of seeds that she inherited from her mother in law. And her husband is kind of angry at her that she didn't first look for their son. But Rosalie has a friend named Gabby, who's another Native American woman, and she has a really different perspective on Rosalie's instincts there. Can you tell us how she responded?

Diane Wilson’s 2020 harvest of native corn, beans, and squash. (Photo: Courtesy of Diane Wilson)

WILSON: So Gabby brought forward that perspective that comes out of a need to survive, and how in difficult times, women have had to make decisions that in immediate were very painful but that allowed their community or their family or their people to survive. And so I felt like that was a perspective that needed to be brought forward, just as the women that I mentioned in the 1862, Dakota March knew that their survival might depend on those seeds. And that I think one of the issues that we face today is the fact that we've forgotten that connection, that our survival literally depends on not only our relationship with seeds, but with water, with all of the other plants around us with animals with all of these gifts that we receive that give us the gift of life.

BASCOMB: Eventually, Rosalie's family along with many other farming families in the area, they're struggling financially, and a company that you call Mangenta comes to town and offers farmers genetically modified seeds, which they promise will yield more corn. The GMO seeds promise more money but there is resistance from some people in town. How did the introduction of GMO seeds affect the community and eventually Rosalie?

WILSON: Well, I really wanted to portray the challenges that farmers are also facing trying to make a living as farmers and to show that evolution of the way that farming has developed, especially since World War II, when big chemical companies got involved and not only found ways to introduce chemicals that were leftover from World War II, but also to make a partnership between the use of chemicals and seeds and start to control the seed inventory in the country. And I think this is really critical history for us to understand that the way farming and gardening began, it was much more of a sustainable practice where people were trying to grow enough to provide food for their communities but as it evolved and became more of a corporate practice, then what we see is decisions that are being made because of a profit, because of a bottom line perspective. And that introduced this idea that our foods, our seeds, our plants our animals our water are all commodities and they can be sold. And if you can look at something as a product as opposed to a relative or a being, then it makes it much easier to rationalize how you're treating those seeds and those plants and those animals.

BASCOMB: Diane if native seeds could talk, what do you think they would say about how we've changed our relationship with land and farming?

WILSON: You know, that was actually one of the questions I asked myself during the writing process. And because I was writing in the first person, it was really important to me to be able to understand each character's viewpoint. And so what the seeds had to say was that there was an original agreement between the seeds and human beings. And in that agreement the seeds gave up their wildness, and in return, agreed to take care of human beings. And the human beings agreed as well to care for the seeds. When you carry that kind of reciprocal relationship, then you end up taking care of each other. And what's happened though, and this is where the story of the way farming has evolved become so important, what's happened is that human beings have forgotten to uphold their side of the relationship and instead have have really taken advantage of seeds in turning them into this genetically modified organism. Is that a way that you would treat a relative? Is that what is best for the seeds themselves? So if you considered the health of the seeds, the rights of seeds as a living organism, then human beings have broken that agreement. And what happens when you break an agreement with another being is that they may just leave. And that's what we've been seeing so much of with you know such a vast proportion of our seeds having already disappeared from the planet that, that lack of care that lack of upholding that relationship means that we're losing one of the most critical sources of diversity on the planet.

Native corn is one of the oldest varieties of corn and it’s the corn that Native Americans taught European settlers how to cultivate. (Photo: Courtesy of Diane Wilson)

BASCOMB: Diane, you're the executive director of the Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance and a lot of your work, as I understand it focuses on building sovereign food systems for Native peoples. And of course though, at the same time, you know, there was a time in the pandemic, when the US Food System really faltered. After that interest in gardening shot way up, but I think a lot of us are still hesitant to try and save our own seeds, you know not quite sure how to go about doing it. And I have to say, I grow a pretty big garden each year and I, you know, the sunflowers drop down and make sunflowers the next year and that's great but I don't really do a lot of seed saving. Can you give us some practical examples of how gardeners can save their seeds? And why do you think it's important to do that?

WILSON: Well, you can grow beans, dry beans are probably the easiest plant to start with in terms of saving your seeds. And there's many beautiful varieties. But if you grow beans to be dried down, then the same bean that you're saving to use in your soup is the bean that you're going to save and use in your garden. And they don't cross pollinate, so you don't have to worry about doing anything to protect them from other species. So beans are fantastic. I think that's probably the easiest one to start with. I think that even if you're not going to save your seeds, it's fun and it's really educational, to even save one. So that you're having that experience or you're having that relationship, you're understanding what is the process of saving seeds and you're going all the way through the cycle with the plant. But the gift of even just saving one of your seeds. One variety is that it teaches you a mindfulness, it teaches you to be present in a way that I think the world around us often pulls us away. You know we're on Zoom a lot and there's all kinds of social media distractions, we're working, we have all these things to do but a seed needs to be tended in its own time. So you pay attention to those seeds in order to have them for the next season.

BASCOMB: And in doing so you're upholding our part of the bargain, as you talked about earlier.

WILSON: Yes. And I think that we have gotten so far away from general practice of seed keeping. But at the same time, there are places that do and a lot of people that do. So, there are seed libraries now, there are you know, Seed Savers in Iowa does a beautiful job of tending seeds so that you have access to good healthy seeds that have been grown organically. So even if you're not saving your seeds to grow out each year, at least be supporting the people and organizations who are caring for seeds.

Minnesota is one of the top United States exporting states for soybeans, corn, livestock products and wheat, most of which are grown via monocropping and genetically modified seeds. (Photo: MPCA, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: And you know, I would think with a changing climate, it's probably more important than ever to have a diversity of seeds. You know, some might be more well adapted to drought conditions that we're going to be seeing in the future, or cold or hotter, or whatever it might be. I mean it's a nice thing to do but it's also a pretty practical thing to do at this point and when we're looking at our own food security.

WILSON: Yeah, I would say it's fairly critical that we be growing the seeds out every year. And I understand the need for a place like Svalbard so that, you know, in case a country does face a catastrophic natural disaster then you know, what happens if your seed inventory gets wiped out, for example then you've got a place like Svalbard that hopefully has that seed banked inventory to replenish your crops. But longer term a place like Svalbard doesn't have the capacity to be able to grow those seeds out. And seeds are living beings so if you're not growing them out, frequently, then they are going to lose viability with each passing year. And even though it's in a deep freeze, that's still losing viability. So at some point, they have to be grown out and if they're not being grown out, they're not adapting. So to me, one of the safest ways to protect your seeds would be if I'm growing out let's say Dakota corn in my garden and then you're growing this corn in your garden and somebody else in another third area is growing it out and if I get hit by hail, then maybe your garden makes it and we can share those seeds back again. Which also, by sharing seeds grown in different regions they're continuing to maintain a very robust viability and adapting to different conditions. And then, of course you know, we all grow out our gardens and in the fall this time of year what's the best thing to do but to get together with your family and your community and share your harvest. So when you're doing seed work, you're building community, you're protecting the seeds and you're also taking care of not only your own health but also the health of the soil.

BASCOMB: And Svalbard for our listeners who maybe aren't familiar with it is a deep underground seed repository, a seed bank.

WILSON: Yeah, it's in Scandinavia, and it was built into a glacier but the glacier is also melting. So I see the utility of it but is that really going to be feasible long term?

BASCOMB: Well Diane, I have to say, I really enjoyed your book I honestly did. It's compelling and it's beautifully written. In the end, what do you hope that readers will take away from this story?

Diane Wilson is a Dakota writer, speaker, and editor, who has published two award-winning books including her most recent novel The Seed Keeper. She is also the Executive Director of the Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance. (Photo: Sarah Whiting)

WILSON: I think more than anything, I would love it if readers would just reflect on what their relationship is to the world around them to the natural world. So that we don't take for granted, the seeds that we grow, we don't take for granted the water that we're provided with and in all the ways in which our food system has been made so easy for us. But at the same time, the sacrifices that have been part of giving up our participation in what is our own creating and growing our own food has meant that the world has really changed a lot and in terms of our relationships to everything around us. And I feel like as human beings, we are really suffering the consequences of that, not only in terms of what's happening in climate change but just in terms of who we are as human beings and what it means when we're raising children who are afraid of bees, who don't know that their food is grown in a garden, who don't know how to steward then the earth that they're going to be in charge of in a few years. So I hope the reader takes that and that sense of responsibility. And that's why I tried to tell the story across multiple generations so that you see it rolling forward that each generation is responsible for doing this work and making sure that the next generation understands their responsibility, and that gets passed on along with the skills to take care of it.

BASCOMB: Diane Wilson is author of the gripping novel The Seed Keeper and executive director of the Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance.

Links

Learn more about the Dakota Commemorative Walk

Civil Eats | “Gardening is Important, but Seed Saving is Crucial”

Learn more about NAFSA, The Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance

Food Diversity and Indigenous Food Systems to Combat Diet-Linked Chronic Diseases

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth