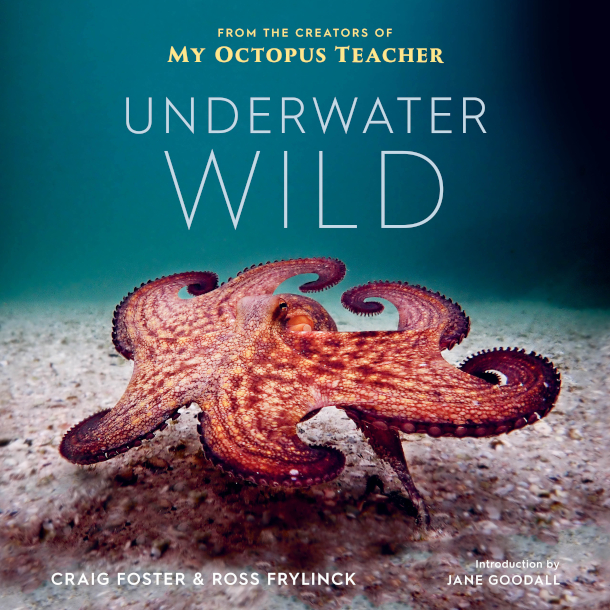

Underwater Wild: My Octopus Teacher's Extraordinary World

Air Date: Week of December 17, 2021

The cover of Underwater Wild: My Octopus Teacher’s Extraordinary World shows an octopus in a pugilistic, or “dymantic” posture, with six of its arms stretched wide. Sometimes the octopus meanwhile uses its other two arms to “walk” bipedally on the ocean floor! (Image: courtesy of Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins)

Underwater explorer Craig Foster dives nearly every day in the near-shore waters of South Africa and it’s here that he befriended an octopus, a relationship captured in the 2020 Academy Award-winning documentary “My Octopus Teacher.” His 2021 book “Underwater Wild: My Octopus Teacher’s Extraordinary World” brings the kelp forest to life with stunning photographs and gripping prose. Craig Foster joined Host Steve Curwood for a recent Living on Earth Book Club event to discuss the power of connecting with wild nature.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Oceans cover about 70 percent of our planet and hold 95 percent of our biosphere, that is places where life can thrive. We humans can relate easily to some marine species, especially whales, dolphins and seals, y’know, mammals who breathe air like we do. But befriending and learning from creatures with gills and without back bones is an unusual pastime for humans, unless you are Craig Foster. Diving virtually every day for years into the near shore waters of South Africa with just a mask, snorkel and flippers, Craig eventually became friends with an octopus and told the story in his 2020 academy award winning documentary, My Octopus Teacher.

[MUSIC FROM THE DOCUMENTARY]

Craig Foster’s daily practice of diving in the shallow waters of the Great African Sea Forest has yielded some fascinating insights into the lives of creatures living there. With friend and diving partner Ross Frylinck, he wrote the 2021 book, Underwater Wild: My Octopus Teacher’s Extraordinary World. The movie itself is compelling and this book is even more amazing, if that’s possible, as it tells the stories of the kelp forest with stunning photographs and gripping prose. Craig joined me from Cape Town for a recent Living on Earth Book Club event. I started by asking him to describe where he dives in this underwater world just offshore.

FOSTER: The Great African Sea Forest stretches from right up Namibia all along the West Coast of South Africa, and then turns around the point and goes a few hundred kilometers up the East Coast. It's about 1,400 kilometers in length. And the actual kelp itself grows to up to 15 meters, or 45 feet, in length. So it feels like you're in a giant, swaying, underwater forest, especially if the water is clear. It's, it's one of the greatest sights on Earth, and the top is, you know, they're heavy leaves that come off the blades, so you get shafts of light coming through the holes in the leaves. And it's this kind of magical dance of light. There are an enormous number of animals in the kelp, living on the kelp itself, on the holdfalts, in the leaves, and then a great biodiversity of animals living around the forest itself.

Craig dives nearly every day in the Great African Sea Forest without a wetsuit or oxygen tank. (Photo: Craig Foster and Ross Frylinck)

CURWOOD: So you get into this forest by doing something that I think most of us would think is torture! The water is not exactly warm there; even in December, I suspect it's probably not above what, 60 degrees Fahrenheit, maybe it's not even 50 degrees Fahrenheit yet. But you swim without a wetsuit! Why do you do this? And you do offer an explanation in your book, so I want you to tell me about your ideas regarding brown fat.

FOSTER: Yeah, so I mean, I grew up, you know, very close to the ocean, so close that the waves used to, you know, break parts of our house down. So I grew up diving from three years old, and we never had wetsuits in those days. So I had, you know, my first ten years of life doing that, and I had, I always in the back of my mind knew that this cold was something special. And whenever I had a difficult time, I used to go back into that, that cold water. And then about ten years ago, I just decided I want to try and dive every day for a decade. And I didn't want to wear the wetsuit, because I wanted to try and adapt my body to the cold and see how that affected me. And what it does is it gives you this incredible lift. There's a big shift in brain chemistry, an enormous amount of dopamine introduced to the brain, the cortisol levels drop radically. So you feel much calmer, and you feel uplifted. So it's this wonderful feeling. And also your, your mind somehow works better. So I do a lot of underwater tracking, and you need to have your mind really engaged. So the cold, ironically, actually helps with that tracking. And you ask about the brown fat. So every baby is born ready for the wild environment. We are wild-born creatures. So it's born with brown fat, which are little pockets that act as thermoregulation devices, they heat the body when it's cold. And if we don't expose ourselves to cold, what happens is this brown fat kind of withers and doesn't become useful. But if you expose yourself over and over again to cold, the brown fat builds up. And sometimes, you know, if you're really feeling good and healthy, because a lot of other parameters have to be in place. You know, you can be in this cold water here and really starting to get quite cold and then suddenly just feel this heat being released by the body. It's an incredible feeling. It's almost ecstatic. And you can feel yourself warming up in that cold and you can keep going. So it's an amazing device that's part of our evolutionary makeup. It's almost like having an inbuilt cloak, a warm coat, but inside your body that just turns on and, and keeps you comfortable.

CURWOOD: I gather, though, that this doesn't happen exactly the first time you go in cold water. How long did it take you to develop your, your brown fat and this remarkable reaction to the cold?

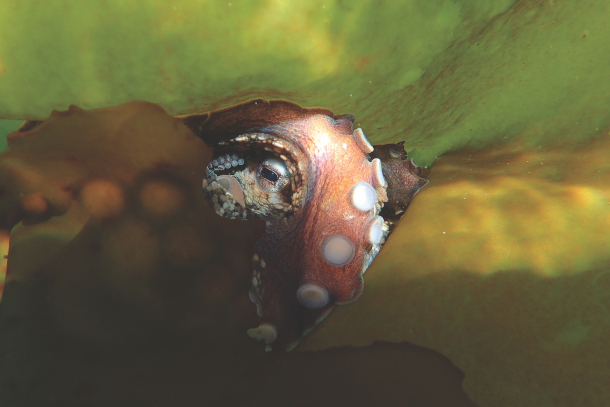

Craig Foster’s “octopus teacher” would wrap kelp fronds around her like a cloak while hiding from pyjama sharks and other predators. (Photo: Craig Foster and Ross Frylinck)

FOSTER: So what I could feel was after about a year of going every day, quite a big difference, stopping shivering after each dive. And then it just seems to increase over the next two or three years gradually. And then of course another big factor with the cold is it seems to improve your immune system dramatically. I used to get ill with flus and colds and things pretty regularly. And I just, I can't remember when I last had a flu or cold or anything like that. So it really does make a massive difference to the immune system.

CURWOOD: Whoa, certainly is very convenient right now in this time of COVID and the stresses that we see around the world, including South Africa to have that ability. So of course we're having this discussion with you, Craig, because of your documentary, My Octopus Teacher, and, you know, one of the most remarkable moments in that film is when she actually extends her arm, a tentacle, and touches your hand. Why do you suppose a wild animal would make contact with a human in this way?

FOSTER: Yeah, it's really strange. And it's not easy to answer that many ways. You know, it's totally mysterious. Not a lot, but quite a few animals will sometimes decide to reach out and make contact with a human. In the case of octopus, or cephalopods, they have a natural curiosity. So their whole lives are balanced between this fear and curiosity. And they're almost like a cat -- you know how curious cats are, they just can't help themselves. And when she's putting that one arm out like that, she's also, all her other arms are attached very strongly to the den. So she wants to know, she wants to feel, she wants to taste -- because they, you know, they can taste with the suckers as well. But she's being very careful. And he's putting the one arm out, and she just can't help herself. What is the strange creature here? What does this thing smell like, taste like? And they, they -- it's curiosity. It's sheer curiosity.

CURWOOD: Craig, you know, here at the, in Boston at the New England Aquarium, I also got to meet an octopus, courtesy of naturalist Sy Montgomery -- named Octavia, I think and she was in a tank, not in the open ocean. And she also extended one of her arms to hug my right arm. And I felt so connected to her. And then I was heartbroken when I learned that she would only live a year. Why such a short life, do you think?

FOSTER: Yes, I had the privilege of speaking to Sy not very long ago and, of course, read her wonderful book. It's quite interesting, you think, you know, these octopus only live for such a short time. I think that was a Giant Pacific Octopus, am I right, Octavia? So I think they live for up to four or five years, but the smaller octopus like my octopus teacher only live for a year, year and a half. And you think, oh my goodness, you know, this is, you know, they're dying, and they're so clever, this can't be good. But it's actually an incredible strategy, especially in the, the difficult world we're, you know, we're facing now with environmental crisis, because animals like cephalopods, that can breed very fast, and live fast and die young kind of thing, are actually much more resilient than animals say like sharks, like the pyjama shark, for instance, grows very slowly, they get up to 35 years old, they mature late, and they're much more vulnerable than cephalopods. So it's actually a very good strategy for survival. And they're one of the animals that do relatively well even under all the pressures we're throwing at them.

The tuberculate cuttlefish is a very soft, small, vulnerable animal that’s a cephalopod like octopuses and “even better” at camouflage than an octopus, Craig says. (Photo: Craig Foster and Ross Frylinck)

CURWOOD: And in your book, by the way, you introduce us to another cephalopod in the kelp forest there: the cuttlefish. And you were lucky enough to witness an incredible display of how cuttlefish have mastered the art of mimicry. This is something you describe on page 159 of your book, but I suspect you can tell us about it from memory.

FOSTER: Yeah, I never can forget! That's the wonderful thing about learning directly from these animals, Steve: it's so powerful and you, you get impacted so heavily that you can never forget a lot of the detail. And I remember very clearly the first day that I saw a tuberculate cuttlefish, this is a small species of cuttlefish that only occurs in South Africa. And they are such masters of camouflage that I, when I looked at this creature, I had no idea what it was. I thought maybe it's a strange piece of algae, or what the hell's going on here? And it was mimicking the algae. And this animal then changed into a cuttlefish and jetted off and left a puff of ink in front of my face, and I was just, like, open-mouthed, gobsmacked. And this animal is even better at camouflage than an octopus, if you can imagine that. It's very small, very vulnerable, soft bodied. So it's got this incredible way of pretending to be a hard-shelled whelk. It changes its whole body shape, and it points its arms, and it changes its color, and even tiny details of these little polychaete worms that grow on the backs of the whelk shells, it even mimics those. So it fools predators into thinking it's a hard shell. It even then sometimes pretends to be a hermit crab living in that hard shell, and drags itself along slowly, when it can actually swim, you know, relatively fast. And then if it has to swim, it can actually mimic a fish called a klipvis that lives in this environment. So this animal is truly the master of mimicry and camouflage, it's quite incredible.

CURWOOD: One of the most enticing aspects of your book is, is the sense that there's much more that's going on in the kelp forest and indeed in nature than just simply one creature finding its prey. That it's just sort of a rough and tumble and difficult and challenging world. You found a lot of cooperation and understanding and affiliation under the seas there, much of which hasn't been documented before. Talk to us a bit about that.

Cuttlefish are masters of mimicry. Here, a cuttlefish in the center of the frame mimics the whelk on the left. (Photo: Craig Foster and Ross Frylinck)

FOSTER: What I found was, there were such unusual alliances, and one of the most interesting alliances was between the tuberculate cuttlefish that we've just spoken about, and one of my favorite fish, which is called the giant clingfish, or rocksucker. And what was incredible is that when the, these fish are adults, they could so easily predate, or eat, the small cuttlefish, I mean, it's absolutely a perfect snack for them. And the other way around as well. An adult cuttlefish would, you know, quite easily eat the young fish. And in fact, they do eat a lot of fish in their environment. But for some reason, which I think I may have worked out, they have formed this ancient alliance, where they completely leave each other alone, and don't predate each other's babies. And you'll see them sitting, you know, right together like friends in these little caves, it's quite remarkable. But it's clever, because they both benefit tremendously from this alliance. And it's, it's been forged over an enormous period of time in this environment. So, and I think, you know, this whole idea of, you know, nature being a kind of environment, where it's just, you know, everything's killing everything else. Certainly, there are a lot of predators, for instance, in the kelp forest, and I see a lot of predations and kills going on every day. But one thing I've also learned is like, if you look at the bigger picture, that the whole biodiversity is in this incredible balance. So, for instance, you know, the pyjama shock is predating the octupus. But it also keeps those octupus numbers in balance, because if it didn't do that, those octopuses would overwhelm a lot of the mollusks, and you'd have a shortage of food, and everyone would suffer, including the octopus. So it's incredible how the biodiversity and this whole living system and this natural intelligence is kind of looking after itself in this wonderful way, and looking after us as well.

CURWOOD: I found it as a reminder of my responsibility as a human, to not just simply be extracting from nature, but to do my role to, to help the other creatures as they, as they help me. We have a question now from a student at the Boston Community Leadership Academy. It's called the McCormack school, it's for grades 7 to 12, and just down the street from our studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston. So let me ask my producer Jenni Doering if she could roll that tape for us.

A giant clingfish, left, and tuberculate cuttlefish, right, sit peacefully side-by-side in a small rock space. Each could harm the other but Craig believes it’s mutually beneficial for both species to remove the other from their lists of potential prey. (Photo: Craig Foster and Ross Frylinck)

JEO: Hi, my name is Jeo. And I'm from the BCLA McCormack. My question is, what is the most amazing thing that you learned while exploring the kelp forest?

FOSTER: Lovely question, thank you. You know, I learned a great deal from my octupus teacher, I learned so much about her behavior and her species' behavior; I learned, you know, I was able to find a new species thanks to her, actually living in her den, an incredible form of mysid that shoals inside the octopus dens. So a lot of incredible behaviors; I have many animal teachers, not only the octupus: specialized fish that surf out of the water, two meters out of the water to get their prey, the limpets and twist them off the rocks. So an extraordinary teaching in animal behavior that came, you know, straight from those animals. But I guess the most powerful thing that I think I learned was that all the animals in the kelp forest, and in fact, all the animals and plants in the ocean and on this planet, make up what we call biodiversity. And this biodiversity has tremendous intelligence, and it is the immune system of our planet. And I realized, and I felt, like actually felt in my heart, how this natural system has kept us alive for 300,000 years. That's how long we've being on this planet as a species, has kept us alive since the very beginning of time. It kept our great, great, great grandfathers and grandmothers alive. And over time, it's just kept us alive and it's still keeping us alive today -- every single breath we take, every mouthful of food. It's all thanks to this great natural system. And it's so important to remember that and do everything we can to help the system and to regenerate her. Because she's our mother. She is our mother of every single human that's ever been on this planet.

[MUSIC: Kevin Smuts, “Pretty Extraordinary Things” on My Octopus Teacher (Music from the Netflix Documentary), Maisie Music Publishing]

CURWOOD: We’re speaking with Craig Foster about the wild and wonderful world of “My Octopus Teacher”. And just after the break he’ll have more stories of animal encounters in the Great African Sea Forest. Stay tuned to Living on Earth!

Gully sharks prowl the Great African Sea Forest. Predators help keep the whole natural system in balance. (Photo: Craig Foster and Ross Frylinck)

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Kevin Smuts, “Basically Flying” on My Octopus Teacher (Music from the Netflix Documentary), Maisie Music Publishing]

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

We’re back now with Craig Foster, the diver and filmmaker whose remarkable connection with an octopus in the nearshore underwater kelp forest of South Africa was captured in his Academy Award-winning documentary, “My Octopus Teacher.” We spoke during a recent Living on Earth Book Club event, soon after the release of his 2021 book, Underwater Wild: My Octopus Teacher’s Extraordinary World, which he coauthored with his diving friend and colleague Ross Frylinck. We continue now with the story of when Ross and Craig encountered a great white shark.

FOSTER: It actually just occurred just off here, where I'm, from where I'm sitting now, only a few hundred meters from where I'm sitting. And we were swimming out, maybe three or four hundred meters out. And we were with a friend, and Ross, who's my friend and co-author, we were a bit ahead. And suddenly, we turned around because our friend was, was shouting, and he'd just seen a huge great white swim past. And you could see the fear and sort of shock in his eyes. And it was sort of circling around towards us. And I mean, it is, you know, if you are not used to sharks, they've been, through Jaws, and all the media and so on, have been blown up into these, like, terrifying creatures that are just after humans and will kill you. And it's really quite the opposite. I had been fortunate enough to spend two years diving with sharks, making a film about great whites and tiger sharks and other sharks, so I was quite used to being with sharks. And I knew that, first of all, they didn't see humans as food, we don't come up on their radar as food. And it's actually quite hard to get close to them. So I was excited that he'd seen the shark. And I wanted to stay and wait for this wonderful encounter. It's a real privilege and it's, it's pretty difficult to see a great white in the wild; they're, they're not very common, and they stay away from humans generally. So the others were a bit horrified that I wanted to wait. But we were in a safe position, we had a big rock behind us. And we were on a shallowish shelf. And one of the things is that you don't want that great white coming underneath you and doing a vertical approach on you in murky water. So we were in a, there's all these protocols when working with these big sharks, and we were actually in a very safe place. And we waited. But unfortunately, that animal, like mostly happens, it wasn't too interested, even perhaps a little bit afraid of these strange creatures and it moved away. But it was, it was a little bit frightening for the others who weren't, you know, hadn't had the privilege of knowing these animals. And Ross has subsequently, you know, got to know sharks much better. And now would, you know, not be afraid in a circumstance like that.

CURWOOD: Yeah, I mean, how close did the great white come to Ross?

Craig’s “octopus teacher” sitting in her den and enjoying a crab she’s caught. (Photo: Craig Foster and Ross Frylinck)

FOSTER: I think it came within, oh, three or four meters, swam past and just cruising along. No aggression whatsoever. But I mean, you see an animal like that, it's a very, it's a large animal that can weigh up to over, over a ton. So it's a large, a large, intimidating shark.

CURWOOD: Of course, your close encounters weren't all with creatures with fins and gills and the ability to stay endlessly underwater. You had a truly remarkable experience with an otter while swimming one day, perhaps you could tell us about that now.

FOSTER: Yeah, these, these animals are really special. It's a Cape clawless otter, so they live on land in holts, in little holes in the rocks and under grasses and things. And then they hunt in the kelp forest every day. But they're extremely shy. I mean, people can be living here for quite a few years and, you know, never having seen one. I mean, you've visited many times here, I know, Steve; have you seen one of these otters?

CURWOOD: I certainly haven't, no, I've even walked among those rocks where you have pictures of their, of where they go. And I've never noticed one.

Cape clawless otter prints on the rocks. They are notoriously shy creatures (Photo: Craig Foster and Ross Frylinck)

FOSTER: Yeah, so they're, it's not an animal that you see often. And you might normally see it from a distance. So I was diving very early in the morning. I think it was winter, pretty freezing cold. And I was like, you know, what am I doing so early here, what's going on? And then I just, out of the corner of my eye, I saw this, this big creature -- they're, I think it's the third biggest otter in the world, it's like a medium sized dog -- like, bouncing off the bottom of the ocean. They go down and they bounce off and all the tiny bubbles come out their fur. And I was -- woah! This is you know, so lucky, just to get a glimpse of this Cape clawless otter underwater in the kelp forest was so exciting. And I just kept my body very, very still. I was, didn't move a muscle. And then I was amazed to see this otter -- curious like you said, what's going on here, now coming in closer to me. And I could sense it was a bit afraid but also very curious. And then it approached, but it approached from behind. So it's thinking, okay, I mustn't get anywhere near this strange creature's mouth. I'm going to approach from behind and see what happens. I just kept dead still. And then I just felt its incredible little hands -- they've got hands not unlike human hands -- feeling my feet! [LAUGHS] And it was absolutely extraordinary, I was just on fire. Forgot about the cold, everything, it was just unbelievable. And then it slowly moved up my body. And then it came right in front of my face. And I stared into that wild face of that Cape clawless otter. And it put its little hands out and started touching my face. And it was just almost too much, I was overwhelmed, absolutely overwhelmed. And then it played with me in the water for maybe ten minutes. And it was almost too much for me, the experience; it was so overwhelming, I got out and sat on a rock, and then the animal approached again. Very strange, mysterious encounter. It's hard to know why they do this. But it perhaps could be that early humans were hunting cooperatively with these animals. And there's still a few places in the world, I believe in Bangladesh, where humans and otters hunt cooperatively and maybe, somehow -- I mean, it's mysterious, this is a big "maybe" -- this animal was kind of remembering some of this evolutionary past and wanted to engage again with this process. Or maybe it was just very curious and bold, and wanted to see what I was and realized, because it's a very intelligent animal, that I wasn't a threat.

CURWOOD: There's another question, back to the octopus -- Nathalie Arias, who's in the eighth grade asks: How have you used what you've learned from the octopus and the experience in your personal life?

A Cape clawless otter. Craig describes an “overwhelming” encounter with one such otter that approached him in the water one day and started playing with him. (Photo: Craig Foster and Ross Frylinck)

FOSTER: Yeah, that's a, that's quite a difficult question in a way. What it did, I mean, initially, that comes to mind is, when you start having relationships with wild animals, and a lot of wild animals, it takes a lot of pressure, strangely enough, off your human relationships. You know, we rely very heavily on human relationships for our well being. But as you start having the relationships with these wild animals, and spending time with them, and I like sometimes spending time alone with them, you kind of feel that -- it's a wonderful feeling -- the pressure off the human relationships. And that is a very positive thing. Because you don't, you're not so needy anymore. But you just want that relationship with that human because you love them, you care for them, and it's not so much you need them. And I think it's something to do with, you know, since, if we go back in time -- and I'm very fascinated with human origins, and I'm fascinated with living wild and how sophisticated early humans were. And I think that it's a natural state, we used to, and we're expecting to have relationships with multiple animals in our environment. So the psyche is expecting that and when we don't have that we put more weight on our human relationships. And that can sometimes be a bit difficult. So that's one of the things that I guess I've, I've got a lot out of that is that I have this, this relationship with these wild animals, and it's improved, I think, my, my human relationships.

CURWOOD: So to what extent does the ocean heal you? I mean, you and your co-author Ross mention in this volume that you've been recovering from emotionally traumatic experiences you, you've had; you talk about divorce, Ross mentions a sad, difficult relationship with his father. So how has the ocean healed you?

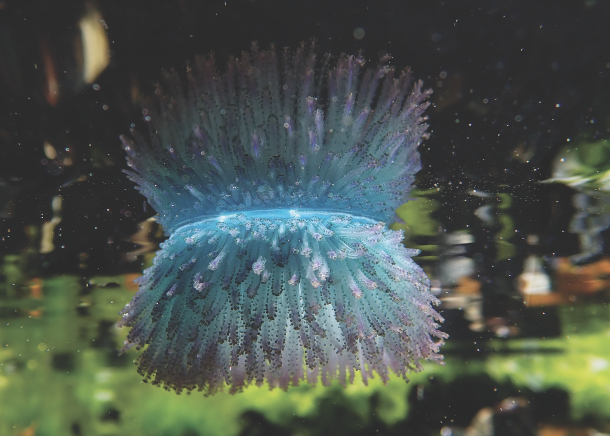

This image of a global bubble-raft shell was taken from below, looking up to the surface. This animal creates a stiff raft out of a stream of bubbles so it can float. They lay their eggs on the raft, too, and that’s what’s visible here: the darker eggs were laid first and have developed more than the newly laid pink ones. (Photo: Craig Foster and Ross Frylinck)

FOSTER: I think in actually in a number of ways. As I say, the daily immersion, almost anybody can be in a, not a very good mood, or quite tired, lethargic. And I promise you, I'll take you into that water, 20 minutes later, you're going to feel completely different. It almost works for everybody. And that's because there is actually a big brain chemistry shift and a physiological shift, and that can last for many hours of the day. And then of course, having a relationship with wild animals changes one dramatically. You feel connected to your environment, you know their behaviors, you have a sense of place, you don't feel so separate a lot of the time, you know, so separate; you feel like you are connected to an environment. And that, psychologically, is very empowering. And it also gives you purpose and meaning because you, the more you know, the more interesting it is. I mean, I just can't wait to get back every day to see what's happening. I've got 20 or 30 mysteries I'm working on. Will I be able to get a little bit further with solving them? Taking photographs and writing down the notes, interacting with a whole group of incredible marine biologists who fascinated with this world. It's an empowering way of living. And you kind of fall in love with wild nature. And I think this is something that's humans have done for a very long time. So you feel kind of a little bit in the human design, you feel like you are doing maybe what you're designed to do. And that feels good. But it's not like this perfect elixir, that you know, you just go and do that and then everything's fine. Of course there's, a lot of things come along, life's difficulties. But it's also incredible to have the tool of the ocean, if I'm struggling, I force myself to go down there, and I force myself in that cold water. And I can normally get out of that difficult space, because it has this, this way of affecting one quite dramatically.

CURWOOD: Craig, speaking of difficult spaces, places -- as a species, we're in trouble. Just look at the ocean, I mean, between climate change, plastic pollution, changing the ocean chemistry to make it more acidic, we're making things difficult for ourselves and for the creatures that are there. How do you think getting closer to the oceans might help us reverse this decline in the way we humans are treating this environment that supports us? I mean, should we all just get in the water and take a look?

The blue button lives on the surface of the sea and is made of a round, flat float and a ring of “tentacles” that are actually a colony of hydroids. (Photo: Craig Foster and Ross Frylinck)

FOSTER: I think we should, I mean, but it's also, doesn't have to be the water. If you are far away from the water, you know, in your backyard, there's, there are insects or if you're even in a city, there are actually, in most cities, there are incredible animals. The biggest, I think, threat in many ways to our environment is this disconnection, or what I call the cooling of the human heart to nature is, in my mind, the greatest threat. And if we don't know creatures, and plants, and fungi, and algae and all these wonderful things, it's hard to care for them. It's hard to make decisions in life to regenerate or benefit nature. So that act of connection is an extraordinary act in empowering oneself and others, to think about system change, to think about ways to regenerate this biodiversity, which is the very lifeblood of ourselves and our planet. And it doesn't matter where you are, or what animals or plants or living forms you get to know. It's just making that connection again, because when you've made the connection, you definitely start thinking and caring about that, that thing you start to love.

Tiny baby tuberculate cuttlefish incubating in their eggs (Photo: Craig Foster and Ross Frylinck)

CURWOOD: Well, it's very attractive. I mean, one might say that you're advocating a quiet reverence, like Jane Goodall, who sat and sat and sat until finally, one of those primates was able to approach her, to make the connection, the way that you made the connection with your octopus, and otter. And so to what extent is the prescription for healing our planet, one of patient waiting and expectation -- waiting and seeing how nature approaches us, as opposed to us trying to thrust our way out into nature?

Craig Foster is cofounder, with Ross Frylinck, of the Sea Change Project and coauthor of Underwater Wild: My Octopus Teacher’s Extraordinary World. (Photo: Swati Thiyagarajan)

FOSTER: That's a wonderful way I think to put it, Steve, and I can hear comes from you having thought a lot about this. Nature is so much more sophisticated than us. We think our technology is so sophisticated, but it's, you know, it's so slow and pathetic compared to the technology of nature. I mean, what she can do at ambient temperature we couldn't even think about doing with our technology. It's quite extraordinary. So she has all the answers. She knows what to do. We're new on this planet, we're the, the new babies on the block, so we need to really listen to her and watch her because I think we can learn so much from her. So I, I love that, love what you're saying, that idea.

CURWOOD: Craig Foster is a co-founder of what he calls the Sea Change Project, and co-author of Underwater Wild: My Octopus Teacher's Extraordinary World. Thank you so much for joining us today, Craig, what a gift.

FOSTER: Thanks so much, Steve.

Links

Watch the full length video recording of Steve and Craig’s conversation

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth