‘Dear Specimen’: Poetry for the Extinction Crisis

Air Date: Week of April 8, 2022

Fossil trilobites at the Zuhl Museum at New Mexico State University (Photo: W. J. Herbert)

For poetry month, a look at a collection of poems that peer deep into the past at species long gone to grapple with the extinctions unfolding today. Poet W. J. Herbert joins Host Steve Curwood to read poems from her “Dear Specimen” collection and explore the role of poetry in revealing and consoling our anxieties about the climate and extinction crises.

Transcript

DOERING: April is Poetry Month and we’re kicking it off with a collection of poems that peers deep into the past at species long gone to grapple with the extinctions unfolding today. “Dear Specimen” by W.J. Herbert examines the extinction crisis through the eyes of a woman who is facing her own death after a terminal diagnosis. But now, rest assured the speaker in the poems is an invented persona and the author herself is alive and well. W.J. Herbert joins me now from Portland, Maine. Welcome to Living on Earth!

HERBERT: Thank you, Steve. I'm glad to be here.

CURWOOD: It's our pleasure. Now many of your poems are in the form of well, let's say it's a one-sided conversation that your speaker is having with fossils and other specimens in a museum. So what inspired this?

HERBERT: Well, the true muse of this collection was the 2016 presidential election, when Trump pulled us out of the Paris Climate Accords, when he began dismantling all the hard-won victories environmental activists and policymakers had fought for, and I felt despair. And on a trip to New Mexico, Las Cruces I'd stumbled upon the Zuhl Museum. And there, fossils of 500-million year old species, extinct species, were displayed beside the few whose descendants survive. And it's at that point that the magnitude of the loss we face really hit me. Those animals, many of them died in the Permian extinction, which took 96% of our marine species and maybe 94% of our terrestrial. And it seemed to me that we were facing this kind of loss, and that we're culpable. And so that's where many of the poems began.

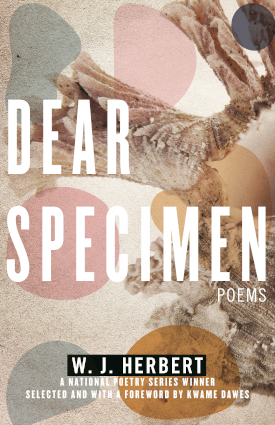

Dear Specimen is a 2020 National Poetry Series winner. (Image: Courtesy of Beacon Press)

CURWOOD: So let's go right to the poetry along the lines of what you've been talking about. I'm thinking of the poem Nautiloid. This is one of these poems where the speaker is directly talking to a fossil. Tell us about the nautiloid creature and, and read the poem for us, please.

HERBERT: Well, the nautiloid that I'm addressing in this poem was the straight-shelled nautiloid, very prolific in the Ordovician, and all the way up until the Permian. And there is an epigraph for this poem:

"Of the 2500 species that evolved in warm, shallow seas, only six survive."

It's called, "Nautiloid."

[READING]

Little squid, you're swimming

as if this black granite

only seconds ago skeined you,

though you haven't siphoned

through your fleshy tube

in 400 million years.

How is it you're still glistening?--

as if reflecting the same sunlight

I felt this morning

as I walked through your sea bed.

It's a desert, now, for coyote

& scavenging rabbit, occasional

jogger with her dog. all the green

-leaved creosote

scorched stones & gravel can gather.

CURWOOD: W.J., tell me, how does the speaker's own terminal illness affect the way that she's looking at these ancient fossils, do you think?

HERBERT: Well, I think the book is making two parallel journeys. The speaker is trying to understand her own personal mortality. But the fossil poems more refer to our species extinction. I think that the specimen poems are the ones where she feels closer, and she is able to notice the minutiae of them. The fossils are so stark, so bare, that I think that she much more easily can look at the specimens that she sees in this collection. And some of the poems are also written about animals that she sees in her environment. And those are the ones that she believes may be able to maybe not help her understand her impending death, but at least help her to understand what it means to be alive.

A tern specimen at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences Discovery Room that inspired the poem “Least Tern” in Dear Specimen (Photo: W. J. Herbert)

CURWOOD: So you could say that this collection is an ode to extinct species. But then on the other hand, maybe you could say it's celebrating them. So tell me though, what is it about these fossils that just so fascinates you and inspire so much wonder?

HERBERT: Well, when you realize how various life was, before we got to this planet, the millions of species that existed before we did, you just have to marvel at their miraculous adaptations, and their beauty in the way they coped with their environment. For example, with the nautiloid, the species that this poem was written about doesn't exist anymore. And all of the very many nautiloid species have virtually disappeared, there is only one left in our present day that you can see. And that's the chambered nautilus, and the fact that this animal was able to adapt by sinking lower in a sea that was becoming increasingly acidic, where oxygen wasn't available. And so the nautiloid in the poem became extinct, but the chambered nautilus survived. And so I was asking questions about survival. Though, it seems like the kind of chaos that we are creating with our fossil fuel extraction and burning is going to create a world where no adaptation will be enough to allow much survival of species. And so by looking at fossils, I can see the deep time reflected in the past, and moving forward in the future, I fear for the loss we face.

CURWOOD: I'd like you to read one of your poems that in my view is very clear and direct about talking about the climate crisis. You call it Tipping Point. Could you read that one, please?

Nautiloid fossils at the Zuhl Museum, New Mexico State University – the inspiration for W. J. Herbert’s poem “Nautiloid” (Photo: W. J. Herbert)

HERBERT: This poem has an epigraph by Greta Thunberg. She spoke at the UN Climate Action Summit in September of 2019. It's a famous quote, she said, "If you choose to fail us, I say we will never forgive you.”

Tipping Point

Fierce heat waves, wildfires, climate refugees,

acidic coral, glacial melt, and look--

a marmoset, orb weaver's filigree,

an algae-coated sloth whose canopy's

on fire, though she gave birth last night. Her nook

inside a lush Brazilian tree

which one sequestered carbon, helped us breathe,

is burning. We've done little to unhook

Earth from this carbon juggernaut, the greed

of fossil fuel producers, energy

that's not renewable, and so you took

your protest to the streets of Karachi,

Cape Town, New York, Bangkok, Berlin, Sydney.

Time's short, you say. From gorge to overlook,

Earth's angry, now, no longer on her knees

and, still, we decimate with each degree:

black rhino, blue whale, leatherback, chinook.

No rainbow, just a grim trajectory.

Marvels archived in dust's dissympathy.

CURWOOD: The climate crisis and the extinction crisis, these things are just so daunting, W.J.; I mean, if one is aware, one must feel some anxiety and grief. So, so how do we not turn away from all this grief and anxiety, and in your view, why is that important?

HERBERT: Well, I think it is true that many of us have a sort of climate PTSD at this point. It's deeply ingrained in us at this point. And for those who are working hard to try to ameliorate this situation, and I'm talking now about this marvelous youth movement that's global, and the many activists who've worked for decades. These people, I feel that they are hungry for a kind of literature, or art, or lived experience that will bring them peace. Yes, we have to keep the climate crisis in the front of our minds so that we can all act together to solve these problems. But at the same time, we need to be calmed. We need to be able to settle down and slow our heartbeats down and open our hearts to receive the kind of calming reassurance that poetry and novels and other kinds of art can can provide for us.

One of the poems in the Dear Specimen collection is titled “Lyuba” after the c. 42,000-year-old baby woolly mammoth specimen unearthed in Siberia in 2007. (Photo: James St. John, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's interesting that in your collection, you openly seek to console the reader. I'm thinking of the poem titled, "After His Nightmare, Sarah Asks." Now Sarah is the daughter of the speaker in this collection, and her young son Seth has just had a nightmare. So Sarah asks her mother to tell Seth a soothing bedtime story. And spoiler alert, it's about manatees. Could you read that for us, please?

HERBERT: Sure, I want to say about manatees, that they are endangered, the species that I'm writing about here, the West Indian Manatee, but they're a peaceful creature that, they're nicknamed sea cows. They graze eight hours a day just below the surface, so their bones are solid, they have to be able to stay submerged. So this poem is midway through the collection. The speaker's daughter's name is Sarah, and she's had a baby. And the boy's name is Seth and he sometimes has nightmares. And so she's calling her mother, asking her mother to tell a bedtime story to Seth. It's called, "After His Nightmare, Sarah Asks."

[READING]

Will you tell him a bedtime story?

"Once a manatee and her calf swam

in a lagoon where herons and egrets feed..."

"What do they eat?" he asks.

"Manatees eat sea grass,

but the calf is so young that it suckles

its mother, and once there was a boy

who, paddling his kayak,

would watch water lap over their great

gray backs."

Seth's quiet. Before he was born,

Sarah, heavy-boned, seemed to float,

undulating

to ebbs and swells as if the moon,

too, was impatient for a baby.

Now via Skype,

I see them snuggling. Above his bed,

a dangling sun. Venus. Mars.

Earth so adrift in the dark,

Seth seems uneasy

beneath it. Does he imagine fevered

soil, poisoned sea grass?

Mom, finish the story!

"I don't know how it ends, Sarah,"

I say, "but the boy loves

the manatees' whiskered faces,

flippers tipped with fingernails,

like his,

and he wonders if the calf

feels as drowsy as he does,

and where

the tide's cradle will carry them."

A mother manatee and her calf (Photo: Sam Farkas, NOAA Photo Library, public domain)

CURWOOD: As we wrap up here, it seems to me that the poems in "Dear Specimen" do all revolve around the central question of, well, how much do we deserve as a species to survive? What do you think?

HERBERT: That's a very tough question. We have this gruesome history as a species of hunting others on this planet to extinction. For example, the Steller's sea cow, which is like the manatee; it was larger, gentle, and was hunted to extinction in the 1800s. We have a very destructive legacy on our planet. So the only thing in my mind that we can put forth as an argument as to why we should continue to exist on this planet are our humility, and our empathy, and our love. These qualities, I think, are ones that, that redeem us in a way.

Author W. J. Herbert (Photo: Peter Ackoff)

I also want to say that, I want to put us into context. We are the only extant species in our genus, everyone else in our genus is gone. And in our family, there are only eight extant great ape species. So we're a small part of the world's millions of animal species. And we Homo sapiens sometimes remove ourselves from the natural world in a way that prevents us from feeling deeply and experiencing the world of others. And by others, I not only mean other people, whose experiences are so different, but I mean other species, who bring richness and biodiversity and really contribute to the web of life on our planet that none of us can live without. We need them all.

CURWOOD: W.J. Herbert's book of poetry "Dear Specimen" received a 2020 National Poetry Series Award. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

HERBERT: Thank you, Steve. It's been a pleasure.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth