Extinction Threatens 1 In 6 U.S. Trees

Air Date: Week of September 30, 2022

Between one in six and one in nine American tree species are threatened with extinction, according to a new study in the journal Plants People Planet. Some of those threatened species are iconic California redwoods (pictured above) and giant sequoia. (Photo: James Lee on Unsplash)

1 in 6 U.S. tree species are at risk of extinction, largely due to pests and disease, according to a recent study published in the journal Plants People Planet. Lead author Abby Meyer joins Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss how climate change threatens American forests, and how conservation efforts can help.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb

Hundreds of scientists from botanic gardens and research institutions across the U.S. recently collaborated on a study assessing the extinction risk of all 881 known American tree species. The study, published in the journal Plants People Planet, found that between 11 and 16% of American trees are threatened with extinction. The top threats to trees are pests and disease, and climate change is expected to increase that risk. Abby Meyer is the Executive Director of Botanic Gardens Conservation International U.S. and a lead author on the study.

MEYER: The impacts of climate change on average are, you know, warmer temperatures, droughts, more intense storms and natural disasters. And that makes species and entire ecosystems more stressed and more vulnerable. And climate change can accelerate the invasion of pests and diseases actually into these weakened forests.

BASCOMB: So trees that are vulnerable, because the climate isn't quite suitable for them anymore, are also more vulnerable to being invaded by pests and things?

MEYER: Yes, exactly. For example, bark beetles, which are one of the largest animal families in the world, surprisingly, they often attack trees that are weakened, so there will be their first target.

BASCOMB: Sure, that makes sense. Well, can you give us a couple examples of tree species that are at risk for extinction?

MEYER: Yeah, absolutely. So we identified 165 threatened tree species in the US. And lots of those are pretty well-known species like oak trees, we identified 17 threatened species of oak. Ash trees, we identified four species of threatened ash. The Fraser fir, which is a really common Christmas tree. Some other really well-known trees include the California redwood and the Giant Sequoia, some of the largest organisms on Earth. And for these species, stress from fire, drought really caused decline and die off of older trees, as well as prevent the regrowth of younger seedlings in the understory.

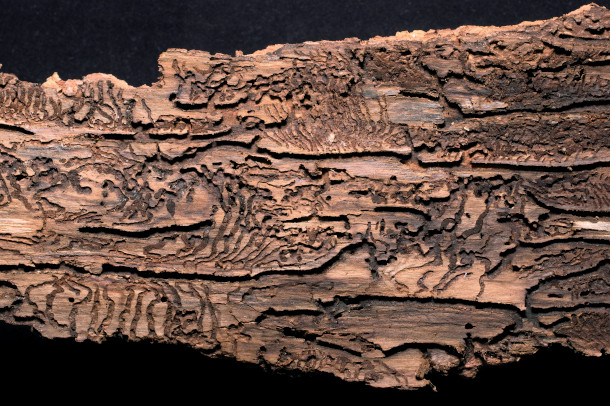

According to the study, the top threats to American trees are pests and disease. Climate change weakens trees, increasing their vulnerability to pests like the bark beetle, which burrow into a tree’s bark as pictured above. (Photo: Immo Wegmann on Unsplash)

BASCOMB: I mean, that's really discouraging to hear, you know, the redwoods and sequoias are also some of the oldest trees in the world, you know, individuals can be older than 1000s of years old. You know, they're able to survive that long imagine all of the changes and fires and things that come through. But now, now, they're not able to survive anymore.

MEYER: Exactly. So you know, for example, California redwood and giant sequoia are both fire-adapted species. So they evolved with seasonal fire happening, but with the intensity of fires that we've been seeing, and also, the rapid rate of change that we've been seeing with our climate, plant species just can't keep up.

BASCOMB: Now, if some species die off because of climate change or pests, as you outlined, I would assume that other species would just move in and take their place. Is that right? And if so, what is at stake with the loss of biodiversity if not the actual numbers of trees?

MEYER: Right, so I think of a forest or any ecosystem really as like a tapestry. And if you start pulling out one thread, and then another, soon, the fabric is not going to be as strong, you can see through it and could be torn more easily. So ecosystems are very similar. And each thread is depending on the other one for strength and durability. So if some species start to disappear, the remaining species become more vulnerable. And also, if certain species are disappearing in a forest matrix, some of the holes that are created in the forest canopy actually become places for new invasive plants and trees to take hold. Oftentimes, the species that can survive well now are the invasive species.

BASCOMB: Right. And I believe, I mean, there's certain other plants and animals that are reliant on specific species of trees. So if you lose one type of tree, you may lose a whole lot more than just that.

MEYER: Precisely. So all of the other species that depend on these trees for survival will be in trouble. Half of the world's animal and plant species rely on trees as their habitat. So in general, the consequences of forest decline are pretty catastrophic.

Trees are keystone species that provide habitat, protection, and food for numerous other species in an ecosystem. A single oak tree, like the one pictured above, can support up to thousands of species on itself. (Photo: Cole Marshall on Unsplash)

BASCOMB: Sure, I mean, one tree could be its own ecosystem, really.

MEYER: Exactly. A single oak, for example, can support hundreds and even thousands of different species on a single tree.

BASCOMB: So trees, I mean, they serve so many functions, you know, they give us oxygen, they provide habitat, and a big one we're concerned about now is sequestering carbon. The US government is relying on trees to offset our greenhouse gas emissions. Given your paper's forecast for so many tree species, how should we be thinking about the carbon storage capacity of our forests?

MEYER: Yes, that's a great question. Forests provide 50% of current carbon storage. So mass tree planting has been looked at in recent times as sort of a silver bullet solution to the climate crisis. And often tree planting initiatives that we've seen across the globe don't factor in biodiversity factors. And we know that diverse native tree communities are more resilient. So to allow for a dynamic and adaptable future forest, each species in forest needs to have a full set of genetic tools to adapt to any future scenario. So our goal right now is to get the right trees in the right places and encourage diversity; that both species diversity and genetic diversity.

BASCOMB: Now, your study found that over 160 tree species may be endangered or threatened, but the federal government only recognizes about eight. Why are those numbers so very different?

MEYER: Yeah. So in North America, we have about 10,000 threatened plant species across the continent, and a very small minority are actually listed on the endangered species list. And that's not a new thing. We've been working within that context for decades. The reason it can take a long time through the petition and proposal process, through a review process, there's also a public comment phase. And that can take years to actually get a species on to the list. It's also worth noting that species that are listed by the Endangered Species Act receive federal protections on federal land. And so the people who are approving species for the endangered species list won't actually approve a species unless it will benefit the species. So say a species exists on only private land or on non-federal land, they won't see the value in that. So that's why we have these other assessment systems outside of the Endangered Species Act that help us keep the pulse on which species are in decline in which species are doing fine.

BASCOMB: Let me just make sure I understand this correctly. You're saying that the Endangered Species Act only applies to federal land? I mean, you can't go out and shoot a California condor, for example, even if it's not on federally-owned land. So is it different for trees for some reason?

MEYER: Exactly. So there is a difference between the protections the animals receive and the protections that plants receive. So plants are protected on federal land, but not on private land, basically.

BASCOMB: You know, another metric of species endangerment is the IUCN's Red List. The red list contains a whole lot more mammal species than tree species, even though there are as many as five times more trees than mammals. I understand there's actually a term for overlooking plant species despite their abundance. Can you tell us about that, please?

Abby Meyer is the Executive Director of Botanic Gardens Conservation International U.S. and a lead author on the 2022 risk assessment study of U.S. trees. (Photo: Courtesy of Abby Meyer)

MEYER: Yes, absolutely. So there is a tendency by people to sort of ignore plants. And we call that plant awareness disparity. Some people call it plant blindness. Really, it comes down to some of the psychological characteristics of humans and how we are drawn to organisms that we can relate to. If we can relate to an animal that moves, that maybe looks like they're expressing emotion, then it makes us care about them. And for plants, we don't have that advantage. And so they're often overlooked. For example, there are more threatened plants than threatened vertebrates and invertebrates combined. Our job is actually much bigger than the animal world. And that's only to say that only 10% of all plants have actually been assessed for their conservation status.

BASCOMB: Well, now that we know so many of our native trees are at risk of extinction, what should be done about it?

MEYER: So conservation action can really take shape in a lot of different ways. That can look like seed banking, where seeds are frozen for up to hundreds of years to buy us some time and to preserve genetic lineages. There's also growing living plants in a garden or in a conservation grove that can be used for reintroduction in the wild or breeding. There's also long-term management of species in wild populations, as well as in these living plant collections or seed orchards. So management of these species through time and that includes genetic management is really crucial as these threatened species populations are dwindling. We need society to value plants and nature so that it gets the conservation attention that it needs.

BASCOMB: Abby Meyer is the executive director of Botanic Gardens Conservation International and lead author of this study. Abby, thank you so much for your time today.

MEYER: Thank you so much for having me. It was fun.

Links

Read the tree extinction risk study

Read a summary of the risk assessment initiative

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth