Climate Disasters and Debt

Air Date: Week of October 28, 2022

The aftermath of Hurricane Maria in Dominican Republic after it hit the Caribbean Island country in September 2017. (Photo: Roosevelt Skerrit, Flickr, Public Domain Mark)

The rich nations of the global north are primarily responsible for historical greenhouse gas emissions. But some of the poorest nations are most impacted and many are crippled by debt related to loss and damage from storms, fires, and droughts. Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood moderated a panel discussion about the climate debt crisis with ProPublica reporter Abrahm Lustgarten; Avinash Persaud, advisor to Barbados’ prime minister Mia Mottley; and Colin Young, executive director of the Caribbean Community Climate Change Center.

Transcript

BASCOMB: The rich nations of the global north are responsible for the vast historical amounts of greenhouse gas emissions. But some of the poorest nations are being crippled by debt related to loss and damage from storms, fires, droughts and other impacts of climate disruption. And after years of talking, but not acting, on loss and damage at the UN climate summits, there are signs a confrontation is brewing for this year’s summit, COP 27, that begins in Egypt on November 6th. A coalition of 20 developing countries recently declared they are considering halting repayment of their debt, totaling more than $600 billion. Maldives former president Mohamad Nasheed spoke for the coalition calling it an injustice that developing nations must take on debt to rebuild from the climate disasters caused by the developed world. Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood recently hosted a panel discussion on the climate change debt crisis along with ProPublica. Panelists included ProPublica reporter Abrahm Lustgarten, Colin Young, executive director of the Caribbean Community Climate Change Center and Avinash Persaud, advisor to Barbados’ Prime Minister Mia Mottley. Steve began with Mr. Persaud and asked him to explain the scale of the climate debt crisis in the Caribbean.

PERSAUD: The countries that are being impacted the most, they're having to deal with this loss and damage, about 50% of the increase in debt in small island states, is caused by mopping up after natural disasters. 50%. The impression given by the international financial institutions is that it’s because they're corrupt is because they're spendthrift. Fifty percent is caused by global warming and other natural disasters. So the climate crisis means for us the debt crisis, and that's why we're campaigning heavily that we need to invest in resilience. And that requires borrowing concessional funding to invest in resilience. Every dollar we spend today, we save $6 or $7 in the future. The problem is, middle income countries, the only countries that can get concessional funding are countries whose income per head is less than $1,253 per year, not per month, per year. Well, 75% of the world's poor don't live in those countries. And so these countries need to be investing in climate resilience. They can't afford it. It's creating these loss and damage, creating these debts. And we're arguing that one of the things we want, one of the three main things we want is that they should have access to concessional funding to invest in climate resilience to avoid the loss and damage. My prime minister famously says they're giving us money after the event is like paying for the undertaker. We want investment now to avoid the loss of lives and loss of livelihoods in the future.

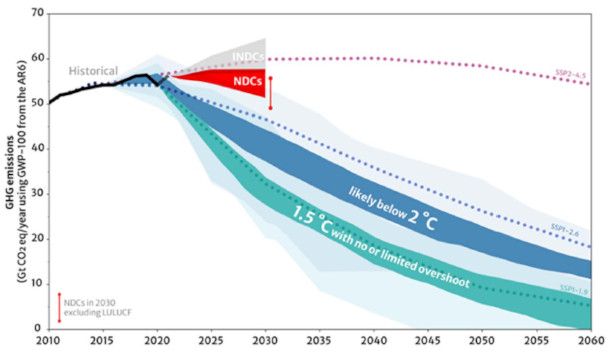

The world is projected to see a 10-percent increase on the greenhouse gas emissions under current climate pledges from countries, according to an analysis from the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) (Photo: Courtesy of UN Climate Change)

CURWOOD: So Colin Young, now you're the executive director of the Caribbean Community Climate Change Center. So tell me, what kinds of investments should these international organizations be making? Of course, I'm thinking of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, which seemed to be a little slow on the uptake here, to put it mildly. I mean, what sort of investments should they be making and, frankly, how much of these investments should be concessional loans and how much of them should be an outright grants, given the responsibility of the rich part of the world for the loss and damage that's occurring right now?

YOUNG: So right off, we will need investments in how to keep out the sea from rising. Not only is that tearing apart our beaches, but it's also salinizing our freshwater systems. The Caribbean has seven of the most water scarce countries in the world. The issue with coastal defenses, however, is that they are public goods and they're critical to our adaptation strategies, but you can't get a rate of return in investing in some of these adaptation initiatives. So those are obviously going to be grants or very highly concessional loans. The other area is in water. We absolutely need to build up the water infrastructure. When you look at the projections, areas will become even more dry. And obviously, this note impacts not only just the availability of water, but it impacts food security, it impacts health. And so we have to look at how do we improve rainwater collection. We look at how do we solid waste management and treatment so we can reuse those waters for agriculture and in recharging our aquifers. Again, this is an area where grants and highly concessional loans will make the most sense because again, they're public goods. Infrastructure, our housing stocks, the fact that most of the infrastructure we have in the region, which is you rightly said, is one of the most climate vulnerable in the world, was not built to accommodate the kind of deluge that we're seeing in rainfall patterns across the region. For every 1 degree Celsius rise in temperature, the air holds 7% more moisture. And so we're starting to see some incredible amount of rainfall where in 12 hours, we're talking about two three feet of, feet, of rain. So obviously our drainage will not be able to accommodate this amount of water. So what you have here is that countries have incurred a significant amount of loss and damage from climate change. In Dominica, it's 85% of the debt is linked to hurricanes. In Belize, you're talking about 7% each year of losses and damages of its GDP that is lost to climate-related disasters. So what has happened is the countries don't have the fiscal space to be able to then invest in rebuilding. And let me say one other point before I end this section here. We don't want to think of these disasters as sequential events because they're happening in parallel. Right, you might have a drought that is ongoing for multiple years, and then you have a significant rain event that may not be a hurricane that can cause 80% damage to your GDP, like what happened with Tropical Storm Erika in Dominica. And then a few years later, you had Maria. And then you have these multiple in parallel disasters that are absolutely at stranglehold on the economies of the region. The moneys that we are getting from the international financial mechanism, they're often too small, too slow to get. And by the time you do get them, you can count multiple, major disasters that would have happened between the time you applied and when you got those financing. If we look at Central America and the dry corridor in Central America, and the areas where there's massive droughts where people can feed their families and feed their kids, there are not many things that cause people to pack up and leave. Drought and not being able to grow food is one of them. Those people will end up in the north. The people from the Caribbean, when we start losing our land to sea level rises and we are projecting our 80% increase under some scenarios of category four and five hurricanes to be hitting our region, that is just going to be a disaster zone. And people will have to move and this issue of migration, there is a tremendous costs, not only to our economies in the region, but to the countries where those people will be ending up. So we also have to look at factoring in those costs of inaction. Because if we don't do and invest in the kinds of things we need to be doing now, the cost is going to quadruple down the road. And there's also going to be issues with political instability in the back door.

CURWOOD: Well, yes and the UN climate facilities the 100 billion dollars a year that was supposed to be coming. I haven't seen that money yet. So what has changed in terms of the evolution of the IMF and World Bank and then the efforts to have this UN climate facility also addres this? Abrahm Lustgarden you reported on this issue for ProPublica, how much of these banks started to move things forward? I mean, to what extent are climate risks and loss and damage now appearing in their calculations?

Avinash Persaud, advisor to Barbados’ Prime Minister Mia Mottley and economist on development finance. (Photo: PMO Barbados, Flickr, Public Domain)

LUSTGARTEN: The short answer is they haven't moved it forward. You know, there have been moments of hope. The agreement, like you mentioned, to raise $100 billion to fund transitions and climate stress countries. I think last time I checked that something around $19 billion had been spent in that agreements from 2015. And if all of that money had been spent, it would just be a pittance compared to what's needed. We see a, you know, a need of something like $50 trillion, to help these countries transition into a more climate safe future. But you hear, you get a sense of the sentiment of where the world is in the comments of people like John Kerry, a couple weeks ago in New York, who dismissed outright, you know, the notion that the United States, the wealthiest country in the world, would pay loss and damages for climate distress countries. And we're going to the COP conference in Egypt in just a couple of weeks. And this is going to be the top of the conversation.

CURWOOD: So Colin Young can you paint us a picture of just how much climate finance is flowing from North to South or from developed countries to those most stressed by climate disruption?

YOUNG: I think developed countries had promised since 2015, a measly $100 billion a year, measly. Look at how much money has flowed to the Ukraine, albeit that is a disaster in its own right, within months, and the entire set of developed countries have been unable to mobilize even $100 billion since 2015. In fact, by the time they meet it, which they promised to in 2023, we would be in deficit by $90 billion, because we're roughly about $70 billion a years what's flowing from north to south. And that's with a very liberal definition of what is called climate finance. Because as you know, one of the issues in the negotiations is that a number of developed countries continue to block the definition of what constitutes climate finance. And once you don't define it, it's hard to actually track what it is.

Colin Young, Executive Director of the Caribbean Community Climate Change Center. (Photo: Courtesy of Caribbean Climate Justice)

CURWOOD: Avi Persaud, the floor is yours now. So how should the more responsible parties in the developed world go about mobilizing the much needed climate finance for countries such as Barbados where you advise the Prime Minister?

PERSAUD: You know, when you sit in the south, we're burning up or we're drowning. And one thing that does is focuses the mind on practical solutions. And I think that two things that's very important for your listeners to appreciate. One is there's a scale problem. The entire global aid budget, aid for everything, aid for clean drinking water, for education, for health, everything is $160 billion per year and it's not going up. It's going down. It's being redirected to foreign policy, sending in stuff to Ukraine has been counting as aid. So you know, that numbers one $160 billion. We need a few trillions a year. We need at least $3 trillion a year to mitigate the climate. We need half a trillion dollars a year to adapt, to the countries that are vulnerable to adapt themselves. We need $250 billion a year to deal with loss and damage. And that's in the most extreme loss and damage as opposed to all loss and damage. We've got a scale problem. And the reality is, no one's giving us grants, no one's writing us a check for that kind of money. We would like them to, they have a moral duty to, they should do. They're not even taking responsibility for it, that's not gonna happen. So the private sector can get involved because a lot of climate mitigation, what we mean by mitigation, so, you know, moving from coal-fired power stations to solar power stations, the private sector is prepared to do that, because there's money in it for them. There's great rates of return in the low carbon transition into energy, transport, agriculture. So we need to use that lever to the full because you know, we have a shortage of money. But you know, what, as Colin said, they're not going to fund seawall defenses. They're not going to fund a new drainage system, because there's no money in it for them. They're not going to repair our leaking taps; there's no money in it for them. They will love to win the contracts, but they're not going to fund it on their balance sheet. And so that's where we need concessional money. By concessional money, we mean, the kind of money that we gave Germany, and we gave Britain after World War II, the kind of money America gave Germany. America gave Germany, this was 30 year money.

ProPublica environmental reporter Abrahm Lustgarten. (Photo: Courtesy of ProPublica)

This was an interesting contract, where Germany didn't have to repay if they didn't have an export surplus. And so any year they didn't have an export surplus didn't repay anything. And then the amount they had to repay was capped at 3.5% of their export earnings, 3.5% of their export earnings. Many developing countries are paying 20-30% of their surpluses. So we need concessional money to invest today for adaptation. But the development banks need to come to the table. At the moment, they're saying, "No, we're not doing concession money to you, because you've got too much money, because your income per head is over $1,253 a year." And then we need money for loss and damage. But we need to limit it. If we ask for money, for cash, for grants for everything, we're then get nothing. So what we're saying is, "Look, we're not asking for everything." We're asking it not for mitigation, we'll get the private sector to help us build solar farms. We're not asking for adaptation, we'll get the World Bank if you give us concessional money to make us a stronger, more resilient place. But when a hurricane has come through and wrecked our economies, and has made a third of the country homeless, then we need cash and grants and we're talking about maybe this is a levies on fossil fuel consumption. Now we're in a cost of living crisis to find a point at make. So one of the things we're proposing is that, okay, don't add to fossil fuels. But when fossil fuel prices are going to fall back after this crisis, they're gonna fall back after the Russian invasion, they're going to fall back at some point after the COVID disruptions. For every 10 percentage points that fossil fuels fall back, the oil price comes back, the gas price comes back, take one of those 10 and put it in to a reconstruction fund for when crisis happens in the frontline states. For every ten put one as because we do need grants for loss and damage. We're not going to get grants for everything. We need concessional money for adaptation and we need to engage the private sector. But the scale of the problem, many people don't understand. But the reality is we need alternative solutions, because we're burning up and drowning.

BASCOMB: That’s Avinash Persaud, advisor to the Prime Minister of Barbados. Colin Young, executive director of the Caribbean Community Climate Change Center, and ProPublica reporter Abrahm Lustgarten speaking with Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood. Thanks to ProPublica for co-hosting the event. You can watch the full discussion at the Living on Earth website loe.org.

Links

Read Abrahm Lustgarten’s report in ProPublica about Barbados’ fight against soaring climate debt

Watch the full panel discussion

Quartz | “COP27 Is All About the Money”

The Third Pole | “Whatever Happens at COP27, Climate Finance Must Be Overhauled”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth