A Treaty to Fight Plastic Waste

Air Date: Week of December 9, 2022

Delegates agreed during the negotiations that the treaty will cover the full life cycle of plastic, from creation to disposal. (Photo: vaidehi shah, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

In March, delegates at the UN Environment Program committed to creating a legally binding agreement to tackle the plastic crisis all the way from production to disposal – its full “life cycle”. And the first of five negotiating meetings, which will eventually produce a treaty document, recently wrapped up in Uruguay. Margaret Spring, the Chief Conservation and Science officer at the Monterey Bay Aquarium, attended the negotiations and joins Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss progress made and the presence of the plastics industry at the talks.

Transcript

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

The world produces around 300 million pounds of plastic each year. Less than 10 percent is recycled, some is incinerated but the vast majority ends up in our landfills and oceans where it pollutes and kills marine life. So, in March, delegates at the UN Environment Program committed to creating a legally binding agreement to tackle the plastic crisis all the way from production to disposal–its full “life cycle”. The first of five negotiating meetings, which will eventually produce a treaty document recently wrapped up in Punta del Este, Uruguay. For more I’m joined now by Margaret Spring, the Chief Conservation and Science Officer at the Monterey Bay Aquarium. She attended the negotiations as an observer and delivered the statement from the science and technology major group at the talks. Margaret, welcome to Living on Earth!

SPRING: Thank you. It's great to be here today.

BASCOMB: Now, there are many different ways to write an international agreement like this. And it's very complicated, of course, and every country has their own interests and opinions on how to go about it. From what I've read, there were two basic approaches to creating the agreement that were discussed here. Can you tell us a bit more about each of those approaches and which countries were sort of leading the charge on each?

SPRING: Okay, well, each country sort of spoke on their own behalf. But if you talk about the countries who are part of the High Ambition Coalition, they're asking for a legally binding convention or treaty with specific control measures in the treaty and uniform rules of the road, essentially, that everyone would have to comply with, and then implement those through national plans of action and reporting. What the United States and others were promoting was to have a general goal in an agreement and to set all of the specific control measures in their national plans. So the country could decide how they wanted to meet that goal, without any uniform rules of the road across the global space. So I think that's the difference, is that the High Ambition Coalition and other countries are more interested in seeing everyone have the same rules, and implement them the way it makes sense in your country. But the US and other approaches were more to say, give us the general goal, and we'll figure out how to implement it at home. It's subtle, but important, because plastic is traded and moves around the globe without much country specific control, always. So really, there was a strong argument for a global agreement on those restrictions.

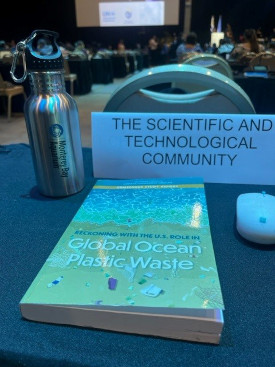

Margaret Spring, who observed the talks for the International Science Council, says delegates were eager to receive scientific input and guidance. (Photo: Courtesy of Margaret Spring)

BASCOMB: Well, the instrument approach favored by the United States is more similar, I think, to the Paris Agreement, which was a landmark agreement, of course, to address greenhouse gas emissions. But that was agreed to seven years ago. And now a lot of observers would agree, I think, that progress on the wonderful goals laid out there have actually been pretty slow in coming, you know, to the frustration of many. So what was the argument to emulate that model when it comes to curbing plastics?

SPRING: The sense I got from that discussion was that the United States was very strongly in support of a zero-plastic pollution in the environment by 2040, which is the same goal articulated by the High Ambition Coalition. It's just that they disagreed on how to get there. There was a concern that a convention approach might take too long. That was one of the arguments put forward by the United States, that it was more nimble. The United States is taking this approach of a national action plan largely because they state they want to avoid delays associated with ratification of a treaty. And most of the civil society there and others really did not agree with the United States approach. And of course, many of the other countries did not.

BASCOMB: Now we know that chemicals like PFAS and phthalates can be found in many plastics, and they pose serious health threats. To what extent were those chemicals and the health problems associated with them included in the discussions here?

SPRING: They were strongly included in discussions here, certainly, partially because they were raised inside meetings by medical professionals as well as interest groups, but also because they were discussed in the context of briefings of delegates. And the delegates, I think, really learned a lot at this meeting from scientists and others about the potential harms that plastics pose. There have been a number of publications recently, in the last year or so that have really raised this issue. But I felt that the people at the meeting themselves were really talking about this a lot and raising really strong concerns about it. And I was representing the International Science Council in my role there. And I did speak, having discussed with a number of other science professionals, the need for action, because the science we had was very strong on those issues.

BASCOMB: Now, how strong was the lobby presence here? I mean, oil and gas companies stand to lose a whole lot of money if we suddenly start curbing our production of plastic. What kind of influence did you see there?

SPRING: There were a number of people there from various industries, whether they're brands versus plastic producers. The plastic producers I think were more interested in discussing ways to improve recycling. And they were very clear about that. There was some interest on maybe, as the issue of chemicals and toxics came up very strongly in these meetings, in opening this up to more transparency, and so they seem to be moving in that direction. The brands, on the other hand, are very concerned, and a number of them were in a business coalition that spoke at the meeting, and a number of them were actually for source reduction. So there's a real split and a real spectrum of industry there. But there's certainly some concerns about some of the plastic producers really slowing the progress, a fear of that. And I didn't see that in the end because I think that the strong voices for moving fast were still there.

BASCOMB: Right. Well, that's the thing. I mean, the other side of that coin is that the companies that are producing these materials that we're so concerned about have a role to play in reducing the problem.

Plastics are fossil fuels in another form & pose a serious threat to human rights, the climate & biodiversity.

— António Guterres (@antonioguterres) December 2, 2022

As negotiations towards an agreement to #BeatPlasticPollution continue, I call on countries to look beyond waste and turn off the tap on plastic.

SPRING: Absolutely. I mean, that's one of the things that came up was that there needs to be a lot more understanding of how these materials are being produced, what's being put in them, and what threats they pose to human health in particular. And that was a very strong topic of discussion, probably stronger here than at previous meetings, which was the concerns about human health, and the leaching of chemicals and toxics from plastics during their use and during disposal. You heard that from the countries where disposal is a real big problem, such as the Southern hemisphere, as well as from public health providers and doctors who were there at the meeting, who were speaking about the dangers of endocrine disruptors and others. And so that information is largely held by the industry without a lot of transparency. And that is where the industry has to be part of the solution.

BASCOMB: Now from what I understand, there were initially several approaches suggested here, one being to eliminate just single use plastics, another to eliminate marine plastic, you know, address that problem. And the last approach was this sort of lifecycle approach, cradle to grave. And that's ultimately what was agreed upon. Can you tell us a bit more about that lifecycle approach? And what is the plan now in terms of addressing plastic from creation to disposal?

SPRING: That's a great question. I mean, the lifecycle approach was embraced. A number of delegates did say that we need to define what's in each phase of the lifecycle clearly, but I heard some people would say, and I would agree, that the extraction phase is an important part of the production cycle. And that's the beginning, the extraction of the materials. Over 90% of plastics are made from fossil feedstocks. So you really have to look at that stage, and then keep moving your way through. So there are some people, I thought, were saying that the plastic lifecycle starts at the creation of the plastic. So that's an area that has got to get sorted out. One piece of plastic can make its way all the way through to the environment, or to a landfill or into recycling. But what happens to it really has to be decided when it's created, or else you're not going to win this game.

Endocrine disrupting chemicals, like PFAS and phthalates, are present in many plastics, and countries emphasized the risks they pose to human health during the treaty talks. (Photo: The Reef-World Foundation, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: Now, this meeting in Uruguay also addressed support for waste pickers. Those are the people who come through waste looking for valuable items to sell. Can you tell us more about that, please? What was decided here?

SPRING: Well, it was very clear that the nations wanted to see the informal waste sector, or some people call them waste pickers, specifically provided for in an agreement. And there was a coalition that was launched at the meeting called the Just Transition Coalition, that was supposed to elevate the role of the waste pickers in the negotiations. And so I think that was achieved. But the specific requirements would be transition for them in whatever the final agreement is for their jobs, but also for improving the health and safety of those workers who really are at risk and working with these materials. And so the the health issues came up with respect to them, as well as the need for an economic solution for these countries and these people who are within that system, and are providing a very excellent role, because they're actually reducing the amount of waste that is going into the environment.

BASCOMB: So what's the take home from this meeting? What actually was accomplished here?

SPRING: So I think we saw a continued commitment by the countries to take urgent action and stick to a fast timeline on this. And there was a strong commitment to a legally binding and cradle to grave a full lifecycle approach, which is great. There was also a really strong commitment to scientific input and guidance on many of these complex issues. And so I think that's going to really be helpful in the long run. What really came through was the need to address both the environment and health dimensions, including human rights, and that civil society or people have to be involved in the negotiation to get this right. Strong support for precautionary principle, polluter pays principles, and the human rights to a healthy environment. And I'm really looking forward to seeing the Secretariat develop what they're calling an elements paper, which would be submitted in advance of the next meeting with core obligations, control measures, voluntary approaches, implementation measures and the like, to help set the stage for the next negotiation. So I think we've set it up for success if we can stay on track.

BASCOMB: Margaret Spring is the Chief Conservation and Science Officer at the Monterey Bay Aquarium. Margaret, thank you so much for your time today.

SPRING: Thanks so much. Appreciate being here.

Links

UNEP | “INC to Develop an International Legally Binding Instrument”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth