Koala: A Natural History and Uncertain Future

Air Date: Week of April 7, 2023

Danielle Clode’s new book, Koala: A Natural History and an Uncertain Future, dives into the world of this iconic creature. (Photo: W.W. Norton & Company)

The koala is an iconic character in Australian wildlife but remains an enigma to many. Danielle Clode, an award-winning Australian author, set out to discover the fascinating story behind the koala’s cuddly image for her new book, Koala: A Natural History and an Uncertain Future. She joined Hosts Steve Curwood and Jenni Doering for a recent Living on Earth Book Club event.

Transcript

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

With fuzzy ears and an oblong nose, the koala is an iconic character in Australian wildlife. But beloved as the koala may be, it remains an enigma to many.

DOERING: Danielle Clode is an award-winning Australian author. And she set out to discover the fascinating story behind the koala’s cuddly image for her new book, Koala: A Natural History and an Uncertain Future. She joined us for a recent Living on Earth Book Club event. Danielle, welcome to Living on Earth!

CLODE: Thank you for having me. It's really wonderful to be here.

DOERING: So I have to ask, koalas of course have such a cuddly image. They're the most adorable creatures, but it's not really true that they're cuddly. Is that right?

CLODE: Yeah, look, it's a tricky one, isn't it? Because koalas can be cuddly, you know, it depends on the personality of the animal. But they are a wild animal. And they can be quite belligerent at times, and definitely prefer to be left on their own. So as far as wild animals go, they're fairly amiable in nature. But nonetheless, they've got some big claws and sharp teeth, so you do have to be careful with them.

CURWOOD: But Danielle, what is it about this adorable face? Why do we respond so strongly to them?

CLODE: I think that there's a lot of things about koalas that really appeal very directly to us. It says more about us than it does about koalas, you know? They have those forward facing features, like a human face, with the eyes and nose. So we as primates are particularly primed, we have special nerve cells that pick up on facial features. And so we're very, very primed to see faces, and koalas really trigger that in us, I think. They have a way of moving and a way of hanging on to things that reminds us of small children. So you know, they are toddler-sized, they appear to cling to you like a toddler does. They make crying noises that trigger a very maternal response. And very often, they will actually lift their arms up when they're seeking assistance. So they really tap into those sort of parental responses we have. And they're fluffy and cute, as well. That doesn't hurt either.

Born the size of a jellybean, a baby koala—or “joey”— must climb into its mother’s marsupial pouch to develop further. (Photo: Taz, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: You just have to wonder what happens in evolution. So let's turn to their diet, which is another thing that's just as intriguing, in some respects, as the desire they create within us to anthropomorphize them. Eucalyptus is toxic at the end of the day, and yet, they pretty much live on it. I mean, how do they extract most of what they need from this essentially toxic plant?

CLODE: Well, that's true, but you know, we should know all about eating toxic things. You know, we love chilies and coffee and all those things that are full of toxins. So the koalas aren't alone in that.

DOERING: Touché.

CLODE: I guess the koalas have managed to exploit a resource that is very abundant in Australia. Eucalyptus are our dominant tree type. And they are difficult for animals to exploit, especially mammals, because their leaves are very tough and fibrous, and they've also got a lot of toxins in them, you're right. So koalas have evolved a really complex system not only of digesting the fibrous food, which is something they would have in common with other herbivores, like sheep and cattle also have these incredibly complicated stomachs. But koalas have the added issue of the toxins. And they have a supercharged liver. So they actually have, you know, a double dose of the genes that animals use to remove toxins. And it's so effective that koalas are actually also extremely resistant to medications. So if they have chlamydia, which is a disease koalas commonly suffer from, a dose of medication to treat chlamydia in a human might take three days. Now the same dose in the much smaller koala takes thirty days to have an effect. So that gives you a good example of how good they are at taking those toxins out of their food.

Author Danielle Clode (pictured) says that koalas’ features naturally tap into our parental instincts. (Photo: Danielle Clode)

DOERING: Wow.

CURWOOD: Now, what about the feeding of the young? I mean, how can the mother koala turn off the normal digestive system for the koalas to get the microbes that they're going to need ultimately to digest those leaves?

CLODE: The first thing is that koalas are marsupials, so they are very different from other eutherian or placental mammals like us. When they're born, they are tiny little pink Jelly Bean things. They're little more than a mouth and a pair of front legs that crawl up into the pouch. And then they have like a second external pregnancy almost. So the babies grow inside the pouch, and are attached to the nipples. The way in which the koalas transfer their babies from a milk diet onto a leaf diet is quite interesting and tricky, because at some point, the mother koala actually ejects a special soup for the baby, which is the contents of a part of the digestive system called the cecum. Which in humans, that's the appendix, but in koalas it's a much larger organ. Our appendix is only about the size of our thumb, and theirs is a meter and a half long. So she ejects that microbial soup and the baby koala eats that soup.

DOERING: Delicious!

While koalas feed on about 70 species of eucalyptus trees, any one individual koala typically prefers between three and ten species. (Photo: Danielle Clode)

CLODE: Which is a pretty messy, disgusting looking thing, it has to be said. There's no other way for it to be described. It's quite horrifying really. But the baby koalas just love it. They can't get enough of it. And that gives them the microbes they need to digest the eucalypts. Not only to digest eucalyptus generally, but quite probably to digest the specific eucalypts that are in the forest they're in, because there's about 70 species of eucalypt that are known to be eaten by koalas, and any one individual koala will only eat between 3 and 10 different species. So they're quite specialized on particular trees. But not only that, they're also specific about which individual trees they'll eat. And it seems to change by season and by day, and that's what makes them so difficult to keep in zoos. They are one of the most expensive animals to keep in zoos, especially overseas, because you can't feed them pellets or a bit of bale of hay like you can other herbivores. They have to have fresh gum leaves, they have to have a lot of fresh gum leaves, and they have to have a really wide choice of gum leaves. Otherwise, you can end up with a koala that's eating, but it will just waste away and die because it's not getting the nutrients it needs.

DOERING: So, Danielle, there's kind of a stereotype that koalas are really cute, but maybe not the brightest animals. How would you respond to that?

CURWOOD: Wait a second! No allusions to the dumb blonde stuff that goes around in our society. You can be cute and smart, can't you?

Koalas’ specialized diet makes them one of the most expensive animals to keep in zoos. (Photo: Danielle Clode)

CLODE: Absolutely. I think there's certainly a very strong narrative going around that koalas are not very bright, and in fact, there's a bit of a myth that marsupials are not very bright. And I think that this sort of, there's a lot of, you know, northern hemisphere Old World bias going on there. As European explorers extended out over the world, they typically were a bit derogatory about species. So marsupials were seen as primitive, maladapted, and stupid. And I think that's simply not true. They're extremely well adapted. And marsupials, if we look at their brain sizes, we find that they're pretty average. The ones that are off the scale are actually the primates. So we're a bit weird. Everything else is fairly standard. But I think the other thing that makes people think that they're a bit stupid is that they sleep a lot. So you know, and that leads to this myth that koalas also sleep a lot, because they eat toxic eucalypt leaves, and that has some sort of bad effect on their brain or their health or even makes them stoned. They're all myths. The koalas are definitely not stoned. They just like relaxing. And it's the same as your dog or your cat. If you give it plenty of food, your dog or your cat will spend a lot of time asleep, because it can. It's got a comfy bed, a nice house, lots of food, doesn't need to worry about predators. And that's exactly what the koalas are doing. They're up a tree, they're fairly safe, all day they've got food all around them. They can just sit back, relax and digest and have a snooze. I mean, it's a perfect life, I think.

DOERING: Sounds like it.

CURWOOD: But it's quite complicated, their environment, they have to find the right kind of eucalyptus tree--the way you write about them, they're far from dumb.

CLODE: Yeah, there's a lot of things going on that we maybe don't give them as much credit for: how they find the trees they want to feed on, is it random? Do they have some sort of cognitive map? We don't really know. But they're very good at finding their dispersed food supply. So to support one koala, you need a forest the size of an average sports field. And in arid areas, it's even bigger. It could be one koala per an area the size of Central Park.

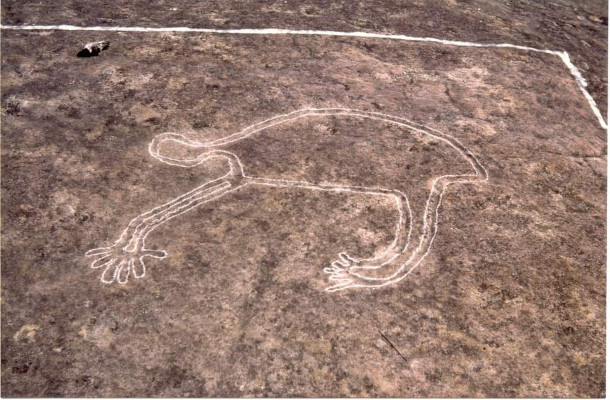

In many Australian aboriginal stories, koalas often rescue or advise humans. An aboriginal rock carving of a koala is pictured above. (Photo: Ralph Hawkins)

CURWOOD: Oh, my. That's almost that's like two square miles.

CLODE: Yeah.

CURWOOD: Speaking of awareness, there's this great scene in your book about a canoe and a koala. Can you can you tell us that story?

CLODE: Yeah, it was a really interesting, you know, some students were up on the River Murray and they noticed a koala stuck in a tree. So they swung the canoe around so that it was touching the tree and the koala watched what they were doing, climbed down into the canoe, and then just sat very comfortably until they swung the canoe around so that it was touching the bank, and then it hopped out and went on its way. And it was just a really interesting little piece of behavior that it was quite clear the koala was watching what the humans were doing. So it had some element of foresight about predicting what these other animals would do in relation to it. But I guess we just don't often think about koalas in those terms.

DOERING: Right. So Danielle, how did koalas figure into the culture of the hundreds of different indigenous peoples of Australia, traditionally, and today?

European explorers exploited koalas for their fur, hunting them to near extinction in the early twentieth century. (Photo: Internet Archive Book Images, Flickr, public domain)

CLODE: Yeah, koalas are a really important species in the dreaming stories of indigenous Australians, so the stories of the ancestral beings that created, you know, the country. And it's really interesting actually, a lot of the stories reflect past climate change events, so at a time when the sea levels rose dramatically. And koalas often feature as an animal that came and rescued humans and helped them get to safety on the land when the sea levels rose. So these stories are really interesting because they actually reflect very ancient geological events. And they tell us that these stories have been preserved for a very long time for, you know, seven or eight thousand years, which is a remarkable length of time to preserve a story. But they have a lot of other meanings as well. And it's difficult for a non-indigenous person to discuss them because the levels of meaning are different depending on the level of knowledge you have in that community. So most of the stories are teaching us about balance in nature, and how to restore balance by listening to the country and listening to the animals. And there's a really lovely story when people are walking through the forest and they're wondering, you know, deciding which path to take, they see a koala. They'll stop and they'll get the advice of the koala. But I really like that idea of slowing down and taking a bit of "koala" time, and taking your time to make decisions and think about where you are and what your place is in the environment.

CURWOOD: Wow. So listen to the koalas, or watch the koalas. And then came a time when Europeans came to Australia. What did the European colonizers think of these fuzzy creatures when they encountered them?

CLODE: Well, surprisingly, they didn't notice them to start with. It took them a while before koalas really came to European attention. And I think it really wasn't until they came to commercial attention that interest really geared up and that was in the late 1800s and early 1900s when the fur trade really was firing up and koala hunting was a huge thing. So we had a huge number of pelts of Australian animals, including koalas, being shipped to the US and UK fur markets. And that really started galvanizing concern in the local community about koalas going extinct.

Herbert Hoover, America’s 31st President, banned the importation of koala and wombat fur in 1930, after Australian conservation advocates implored him to take action to save the species. (Photo: Opus Penguin, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DOERING: Yeah, you write in your book about that koala fur was maybe even being used, along with some other marsupial fur, in children’s toys, you know, making a stuffed koala, like a teddy bear. And this was around the time when teddy bears were becoming popular as well. And they were using koala fur in some cases.

CLODE: Yeah, the idea of having a toy koala made out of actual koala fur is pretty horrifying. But I think that it's interesting, the children's toys then became part of a conservation movement, which was really prompted by you know, this is a really good example. It's a classic Australian book: Blinky Bill by Dorothy Wall. And this is really a book that really teaches kids about koalas and really sends a really good conservation message. You know, it's about koalas being displaced out of their habitat. It's about the interactions with humans, the threats they face, and how they survive. I mean, it's also a really fun story about a naughty little koala. But those children's writers who wrote about koalas were one of the really big galvanizing public campaigns to protect koalas. Really, it was actually really interesting that although there was a lot of public campaigns to stop koala hunting, it continued right up until 1930. And the thing that stopped it was that the conservationists made an appeal to Herbert Hoover, the American President, because he had lived in Australia and had a particular fondness for Australia. And they appealed to him to do something about the koala hunting and he banned the importation of fur from Australia. And that dried up the trade and stopped the hunting. So American conservation efforts have really played a very important role in koala conservation.

CURWOOD: So let's talk about the habitat situation for koalas. If anyone was paying attention to the news a summer ago, the horrific fires and pictures of koalas sort of treed by flame, and horrible body counts. What's the risk of extinction from habitat loss for these animals?

The 2019-2020 Australian bushfire season, known as Black Summer due to its historic intensity, killed or injured thousands of koalas. (Photo: robdownunder, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CLODE: Obviously, Australia, like a lot of places, has lost a lot of forest cover. So you know, we have cut down a lot of our forests. So that definitely plays a big role in the problems koalas face. So koala populations are declining quite precipitously, and quite worryingly, along the east coast, and that's why they've been declared endangered in those areas. In other areas, though, they are actually increasing. So in Victoria, in the south, where they almost went extinct through hunting, they have come back through a translocation program. That's a very strong population. And the same thing has happened in South Australia. And those populations are booming. But I guess that what that tells us in both cases, is that some of the problems we have with fragmentation of habitat. So you know, on the east coast koalas are trapped in forested areas, they don't have areas to move out to, they can't disperse. They can't maintain their populations. They have disease problems, you know, through close proximity. As we know, when we're stuck in a small area disease transmission is a problem. And in the south, where we have a lot of koalas, they're still in fragmented habitat. So even though they're doing really well, they have nowhere to go. And we have overpopulation problems. So we actually have koalas killing the forest. So you have sort of opposite problems, but they're caused probably by similar things. And that's the fragmentation of habitat and the loss of habitat. So we need to find ways of making sure that when we are doing developments, we make sure they're wildlife friendly. We put corridors in, we protect, you know, that we make sure the roads don't fragment the habitat, that the animals can move across them. And in terms of climate change, bushfires are increasing, which causes an additional problem because the forests are highly flammable in Australia. And if we've only got small areas of forest left, and those patches burn, there's no other food for the koalas to access. And that's when extinction really happens in local areas.

DOERING: Well, Danielle, what can be done to protect koalas now? What do you see on the horizon for them at this point?

A bushfire rages near the author’s home, where koalas are abundant. (Photo: Danielle Clode)

CLODE: I think one of the main things I got out of doing this research and looking at them across the whole country and back into their pre history, and the evolutionary history as well, is just how resilient and robust koalas are. They have come back from multiple near extinction events, not just the hunting, but also the Ice Age extinction event that wiped out a lot of the megafauna around the world. So they're a really really resilient species. And if koalas are struggling the way they are on the east coast, I suggest that means we're doing something really dramatically wrong. I think it suggests that we do need to completely shift our focus in how we run our economies and manage our development and how we live with the world. And we do need to find a more compatible, more sustainable way of living with a stronger environmental foundation, which is better for us and also better for koalas and all the other species.

CURWOOD: I just want to say thank you for taking the time with us today. It's a marvelous, fascinating book.

DOERING: Thank you so much, Danielle. It's been a real pleasure to speak with you.

CLODE: Thank you for having me. It's been marvelous.

DOERING: Danielle Clode’s new book is called Koala: A Natural History and An Uncertain Future.

Links

Watch the full interview with author Danielle Clode of "Koala"

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth