Jellyfish Age Backwards: Nature's Secrets to Longevity

Air Date: Week of April 28, 2023

Jellyfish Age Backwards: Nature’s Secrets to Longevity is the new book by Nicklas Brendborg (Photo: Courtesy of Little, Brown and Company)

In nature, some animals live far longer than humans, and some don’t appear to age at all. One species of jellyfish can continually revert back to a juvenile stage, making it essentially immortal. Author Nicklas Brendborg explores this and more in his new book, “Jellyfish Age Backwards: Nature’s Secrets to Longevity,” and he joins Host Paloma Beltran to share how humans can live longer.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

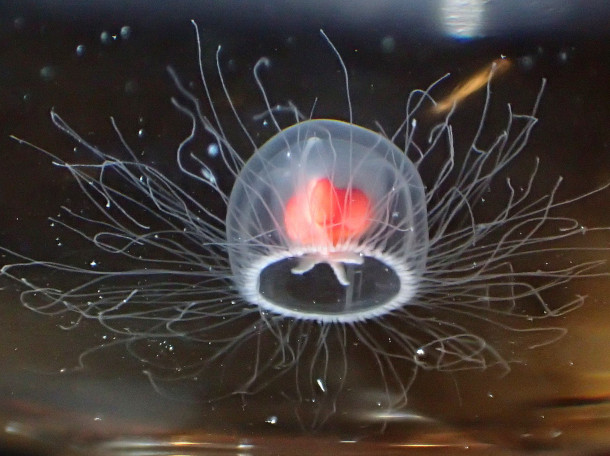

The average human lifespan has increased dramatically with modern medicine and improved nutrition but in nature some animals live far longer than humans. And some don’t appear to age at all. The jellyfish turritopsis dhornii, that can continually revert back to a juvenile stage. In his new book “Jellyfish Age Backwards: Nature’s Secrets to Longevity”, Nicklas Brendborg explains what we can learn from animals about aging and how humans can live longer. He starts by explaining the title of his book.

BRENDBORG: My book title refers to a type of jellyfish called Turritopsis, which is this tiny jellyfish around the size of a fingernail, it has the ability to actually rejuvenate itself. So what actually happens is that you stress it somehow, for instance, by increasing the temperature in the water or increasing the salinity, or maybe starving the jellyfish a little. And then it can go from what is called the adult stage, so the stage that we know it from, back to something called the polyp stage. That would be akin to a butterfly turning back into a caterpillar. Then from there, the jellyfish can grow up anew, and then it can just go around in this cycle again and again and again. Of course, this jellyfish doesn't live forever out in nature where it lives in this big, big ocean, here it's gonna get eaten by something eventually. But at least in the laboratory no one has actually found a limit to how much you can make this jellyfish rejuvenate itself. So it's quite possible that as long as it had scientists to take care of it, you could actually make it live forever. So in principle, you can say it's an example of the holy grail of aging research, so that is an animal that can practically live forever, at least under human protection.

BELTRAN: So why does a human body age? We tend to think of aging as sort of this bad thing, but as you note in your book, biology all makes sense in the light of evolution. So does nature have a good reason?

Nicklas Brendborg is the author of Jellyfish Age Backwards: Nature’s Secrets to Longevity (Photo: Courtesy of Little, Brown and Company)

BRENDBORG: Yeah, so that's what you could call maybe the million dollar question: why do we age? For most organisms, it makes more sense to focus more on reproducing right now instead of, you know, having perfect upkeep of the body sometime in the future. So you can imagine if you are a mouse, even if you had like immortality, you wouldn't live forever, because you will get eaten by something anyways. So then it makes more sense to take the limited resources you have, put them into just having as many offspring as possible so that you get descendants. Then, of course, that will predict that an animal like humans, who will have a lot fewer predators and a lower risk of death from other causes as well, then we would have evolved longer lifespans, and that's what we see. But yeah, at this point, we know some of the stuff that goes wrong, but why this stuff goes wrong in the first place is still an open question.

BELTRAN: And you write about various organisms that don't age like humans, can you describe some of the studies in your book involving animals?

BRENDBORG: Yes, so the exciting thing about animal research, when it comes to aging, is that that's really the way where we can get a feel for what's possible, by looking out into nature. For instance, many humans live maybe between 70 and 90 years. But if we look out into nature, you can find another mammal, the bowhead whale, which lives more than 200 years, you can find one of its neighbors, actually, the Greenland shark, which can live around 400 years. And we even also know animals like lobsters that don't age physically. And then animals like this jellyfish that my book is named after, Turritopsis, which can rejuvenate itself, so age backwards.

BELTRAN: Does this mean that it's not necessary that humans age? Is there a reason to believe that we can learn how to combine abilities that stop other organisms from suffering from aging, and maybe use that for humans?

Turritopsis dohrnii, the jellyfish Nicklas Brendborg’s book is named for, can transform from its adult medusa form back to its polyp form. (Photo: Tony Wills, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

BRENDBORG: We might describe aging as some sort of almost physical law where you just take a quick look and say, well, you know, we do see a lot of the same changes in an old mouse or an old dog or an old person, but it just, first of all, happens at wildly different speeds. So a mouse that's two or three years old, will have like gray hair, it has lost muscle mass and bone mass, and it's, you know, just gotten kind of slow, like people also get when we get old, but it just happens in a timespan when a human is still an infant. And then, if you look at humans, well, the time point when all of this stuff happens to us, a bowhead whale would still be young, or Greenland shark would still be young, and so on. So at least we can say that there might be a limit somewhere for how long a complex organism can live, but humans are just nowhere near it. So it seems that there's actually quite a lot more potential. And then we have these few species that then also suggest that, well, maybe it's possible to have a biological organism that doesn't age at all. So like the next step over.

BELTRAN: Tell us about the idea of hormesis and how it can be seen in our lifestyle, and our diet and in our surroundings.

Bowhead whales can live for over 200 years (Photo: Bureau of Global Public Affairs, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

BRENDBORG: Hormesis is one of these phenomena that we have uncovered, you could say, by studying a lot of different ways to prolong life. Throughout time, researchers have just noticed that a lot of these life-extending treatments, they tend to have something in common and that is that they are actually kind of bad for you. So researchers have, for instance used radiation, like small doses of radiation, to extend the life of mice. They've used different kinds of toxin to extend the life of laboratory worms. And that is, of course, not because that these things are actually beneficial it's because they are a stress factor to the body. So of course, if you get a high dose of radiation, you get cancer and you die early, and get a high dose of toxins, you also die. But at a low level, the way this works is basically that the stress factor will turn on different processes in the body associated with repair, and like bodily upkeep, to combat the stress. And this can actually help then make you stronger in the long run. So hormesis could be understood as like the scientific version of 'what doesn't kill you makes you stronger'. And the best way to really understand it like from your own experience is this is basically what happens when you do exercise. So exercise is really, really good if you want to live a long life, if you want to be healthy in general, I think most people know that. But most people don't really know what it is about exercise that is so healthy, like you might think that it's while you're out for a run that you're really benefiting yourself. But if you think about what happens while you're out for a run, like you get a high pulse, you get a high blood pressure, your muscles and bones get damaged, your lungs are stressed, none of those things are healthy in isolation. So most of your organ systems actually stressed or taking damage, and that's, of course, also why your brain is trying to make you stop and telling you to just, you know, start walking and go home. That's because you are damaging yourself. But the magic really happens when you then stop running. Because then the body sees all of this damage and it basically interprets this as a kind of signal that says you need to get stronger. So it starts all these processes, as I said, involved in repair, in upkeep, in strengthening, so the next time you go for a run, then you have stronger muscles than before, and a stronger heart, and stronger bones, and stronger lungs.

BELTRAN: Yeah, so not all stress is bad...

BRENDBORG: Not all stress is bad, it's about the dose.

BELTRAN: And what about food? So we all know that eating more plant foods is good for us, having a green-rich diet, but that has to do a little bit also with hormesis, as you point out in your book. How does that work?

Greenland sharks can live for over 400 years (Photo: Hemming1952, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

BRENDBORG: So there's all these fun studies coming out that you probably encountered where you, for instance, hear that the healthy part of blueberries is this one compound, or the healthy part of grapes is this other compound. And, you know, that might very well be true that some of the health benefits come from these compounds. But a lot of the times if you track what happens if you give to humans, they actually tend to, you know, go to the liver, the liver is involved in detoxification, that's why alcohol goes there. But like, really any, like, drug will go there as well, anything that the body needs to like, make safe and then clear out of the body. So a lot of these compounds do seem to be slightly toxic, actually. So, both that they go to the liver, they can also be harmful in high doses. And also from like a theoretical perspective, we know that just like you and I don't want to get eaten by something, that's actually the same thing for plants, they don't want to, you know, become dinner either. But we have all these abilities to run away or fight and hide, maybe. A plant is just sitting there so it can't do any of these things. So the way plants solve this problem is basically chemical warfare. So there's just an insane amount of plants that are toxic in some way or the other. So a lot of plants we would get like really sick or maybe even die from it. But even the plants that we do eat actually also tend to have various toxins maybe to protect against us, but maybe to protect against insects or other animals that could eat them. So then when when we know this theory of hormesis that could explain why, even if they are a little toxic, why is it so healthy to eat all these plants? Well, we get the same response where it's this slight stress response that then sets in motion all these bodily upkeep functions and then we end up stronger than if we exclude these low level toxins.

BELTRAN: Fascinating. And it's not just about subjecting ourselves to mild damage in order to grow back stronger. Something else you point out in your book is dental floss. And many of us are not regular with flossing. Why do you find that dental floss and flossing is so beneficial?

Exercising stresses your body which causes it to begin repair and strengthening processes, ultimately making you stronger and healthier (Photo: pxfuel)

BRENDBORG: Yeah, so I have a chapter called "Flossing for Longevity" and it is basically because the human body is not sterile in the sense that it's not free of bacteria, viruses, fungi and so on. It's actually teeming with all these microorganisms. And most of these microorganisms are neutral. They don't really affect us that much. They've found, you know, a nice warm place to live, where there's abundant food, and then they just take care of themselves. Then we have some that help us, for instance in the gut or they help with our immune system. But then we also have some that are harmful. And for some reason, a lot of the ones that get identified as harmful, they tend to, you know, originate in the mouth. So there's a certain bacteria in the mouth that keeps popping up inside the brains of people who died from Alzheimer's, dementia, but not in the brains of people who died from other causes. It keeps popping up inside the clot that forms when you have, say, a heart attack or a stroke. Then there's another bacteria from the mouth that keeps popping up in colon cancer and cancer of the pancreas. So there are these bacteria, that, you know, we find these weird places where they don't belong in connection with disease, then we also know that this infectious condition in the mouth called periodontitis, where you kind of have bacteria growth out of control, and this condition also increases the risk of all these different diseases. So I'm not saying that these bacteria are like the ultimate cause of these diseases, but it is very likely that they at least contribute to the diseases. But luckily, it's very easy to avoid, because bacteria have a simple way of life, they just take food and convert it into more bacteria. So if you want to lessen your bacterial burden in the mouth, you can have less food stuck, for instance, between your teeth, and then they have less to eat, and you decrease your risk of say, getting periodontitis, or just in general having these bacteria grow out of control. So the chapter is called "Flossing for Longevity," it, of course, also encompasses brushing your teeth, just generally keeping your mouth healthy, I guess would be the advice, and then you can, in like two minutes a day, really decrease your risk of all these different diseases.

BELTRAN: Yeah, better safe than sorry, right, in terms of bacteria in your mouth?

BRENDBORG: Exactly. And, you know, most health advice is, like, really hard to follow, say you have to exercise or have to eat really healthy and all that stuff. So I'm, of course, also always on the lookout for these things that are just simple, easy to do, and will benefit you. Because we of course, all want to do all the required amount of exercise and never eat, you know, stuff that we shouldn't or drink too much alcohol and so on. But it's just extra beneficial when we can find these small little things that can make a big difference.

BELTRAN: Yeah. What are other examples of maybe small little things like flossing your teeth, that can make a difference in your health and longevity?

Many plant foods, such as blueberries, have slightly toxic compounds in them that stimulate strengthening processes in your body (Photo: pxfuel)

BRENDBORG: I think, of course, we just quickly have to mention, you know, don't smoke, that's like the number one. If you are someone who is smoking and you only do one thing, just stop smoking. And it doesn't even matter what age you are, we can see that even people who are in, like, their seventies, and they stop smoking, you're not going to return to baseline, but you're at least going to, you know, increase your chance of getting more good years by stopping at any point. But besides that, I think that it's also very important to have a look on the like mental aspect of this. Because we know a lot about how influential our brain is to our physical health. And we can actually see that one of the factors that's most tightly associated with an early death is loneliness. So people that are lonely tend to have a high risk of many kinds of diseases, and also to die earlier. Also, people who have depression tend to have an increase in their brain aging, so their brain ages faster. And in general, if you ask these anthropologists that go to some of these long-lived communities and, you know, interview them and try to work out what's so different, they always come back and say that these are people that are extremely, first of all optimistic and tend to be kind of worry-free. And then they also tend to be very deeply committed to their community, so they have very strong social ties, and they have these strong feelings of meaning in their life, which doesn't have to be some crazy thing that they have a mission to earn a crazy amount of money or go all around the world, but mostly just like maybe they have a couple of grandkids and their mission is to help these kids thrive or to make sure their community is doing well or they're just always very, very sure of the fact that their life has a purpose. So there are these, you know, hard-to-tease-out ways that your mental health definitely affects your physical health.

BELTRAN: Yeah, and of course, one of the conclusions that you point out in the book is that people are different from each other. Literally what our bodies are made of and how we are programmed at the genetic level. That gives us different experiences with the same pathogens or treatments. For example, some people can digest milk while others can get diarrhea. So how do we approach finding what's right for us if we can't necessarily listen to general statements about what we do, or what we put in our bodies?

Flossing and keeping your mouth healthy prevents gum disease, but also may reduce your risk of Alzheimer’s disease, heart attack, stroke, and cancer (Photo: Marco Verch, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BRENDBORG: I mean, imagine if you're trying to figure out, is milk healthy or not? And then you have some of the study subjects and they're like, "oh, yeah, I love my milk," and you know, you can see it helps them grow taller, and all these health benefits. And then other people just feel sick every time they get it and just, you know, really benefit from removing it. And also, when you look at studies of big effects, they say, "oh, you know, if you eat spinach or something, your muscles will grow 20%." Well, if you look at, then, the different participants in that study, some of them might have 50% muscle growth, some of them might even have lost muscle. That's because you know, people are not the same. So, at the end of the day, of course, all these studies is the best way to get inspiration. But you have to also, you know, apply it on yourself, and then make sure whether it works as it's supposed to do or whether your body is different for a reason. We're gonna find the same thing later on as we dive deeper into genetics that, of course, sometimes if there's a dispute about what diet makes people feel better, well, both camps actually right because their bodies are just not the same. So we're already moving into this point of, you know, personalized medicine where if you, for instance, sequence the genome of a person, and that will be different for all of us, and then try to look, are there any things that you should be especially cautious about? So, are you likely to more quickly get, like, high cholesterol? So you have a higher risk of a heart attack, for instance. Have you got an increased risk of getting dementia? And all these things, so then you can maybe customize your health goals after that so that, you know, you hit the areas that are most likely to benefit you in particular.

BELTRAN: Nicklas Brendborg is the author of "Jellyfish Age Backwards: Nature's Secrets to Longevity." Thank you for joining us, Nicklas.

BRENDBORG: Thanks so much for having me.

Links

Learn more about Nicklas Brendborg’s research on his website

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth