PFAS Added to Plastic Containers

Air Date: Week of June 30, 2023

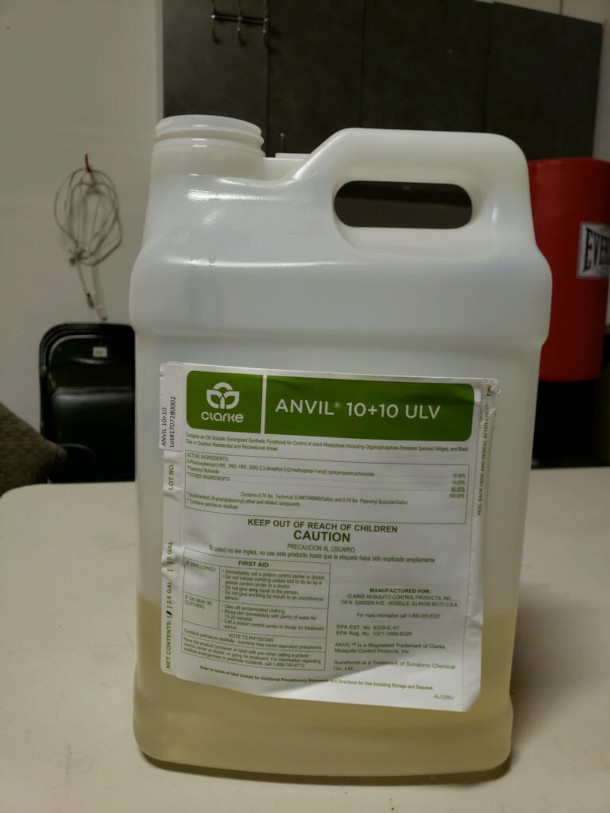

A pesticide called Anvil 10+10 was found to have high levels of PFAS due to the plastic containers it was stored in. (Photo: Courtesy of Kyla Bennett)

PFAS “forever chemicals,” linked to cancer, liver problems and more, are leaching into cosmetics, household cleaners, and even food stored in plastic containers treated with fluorination. EPA is now going after a company that uses the fluorination process, but some advocates say the agency still isn’t doing enough to protect the public. Kyla Bennett of Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility joins Host Paloma Beltran to explain the public health risks of this source of PFAS.

Transcript

O’NEILL: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston this is Living on Earth. I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

PFAS chemicals are one of the top chemical exposure concerns these days, linked to cancer, liver problems and high cholesterol. These “forever” chemicals have been widely used in firefighting foam, non-stick pans, rain gear and more. And they’ve gotten out into the environment to contaminate drinking water. Now it appears that PFAS chemicals are sometimes found in a wide variety of plastic containers that hold cosmetics, household cleaners, and even food. With some prodding from watchdog groups, the U.S. federal government is now going after a company called Inhance Technologies, that uses a fluorination process to make plastic containers more durable for their clients. But that ends up creating PFAS chemicals that leach into the contents at high levels. And tracing back that contamination to its source has taken some persistence from people like Kyla Bennett. She’s the Science Policy Director for Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, or PEER, which teamed up with the Center for Environmental Health to sound the alarm about the PFAS in these plastic containers. Kyla Bennett, welcome back to Living on Earth!

BENNETT: Thank you so much for having me.

BELTRAN: So, I understand that you stumbled upon the fact that these Inhance containers have PFAS by accident. What happened there?

BENNETT: So, what happened is I became aware of the whole PFAS contamination issue in 2018. And I decided to test my town's water to figure out if we were contaminated. I wanted to use my town as a control because I thought, here in Easton, Massachusetts, we've got no Department of Defense facility, no industry, no firefighter training facility that would lead to contamination. So, I tested our water and then also Sudbury's water, which was right next to a firefighting training facility. And to my surprise, Easton's water came back more contaminated than Sudbury's. So, I started trying to figure out why we were contaminated. And I was looking at a map from Mass DEP. And there was a cluster of towns in southeastern Massachusetts that had high levels of PFAS in their wells. So, the only thing I could think of that they all had in common was that we got sprayed by aerial planes and trucks with a pesticide called Anvil 10+10. And I was wondering if there was PFAS in that pesticide. So, I asked DEP -- they said no. They asked EPA -- EPA said no. And I didn't trust them, so I tested it myself. And we found pretty high levels of PFAS in the Anvil. And that kicked off this whole thing, opened this Pandora's box. And EPA was actually the one who figured out that the PFAS in the Anvil was actually from the fluorinated containers.

BELTRAN: Wow, Pandora's box indeed. You know, we're talking about plastic containers here. How exactly did the PFAS get into the containers?

BENNETT: So, we're talking about a particular kind of plastic container, these are the high-density polyethylene, the HDPE, which is the number two when you're recycling. So, when you see that little number two recycling symbol, that's that type of plastic. And what happens is Inhance takes these already formed number two plastics in their facilities, and they put them in a chamber, suck out as much oxygen as they can, they raise the temperature, and they blast these containers with fluorine gas. And this fluorine gas reacts with oxygen in the air and with the oxygen that's in the plastic itself and forms these PFAS. So, it's not intentional, but it is something that's known that happens, and the levels are quite high. And what happens is this fluorinated layer on these plastic containers make them non-permeable, so it prevents things that either have flavorings or smells or are corrosive from leaching out.

BELTRAN: And what kinds of things are these containers used for? Are these regular household containers that I can find in my kitchen cabinet?

BENNETT: Unfortunately, they are. They are containers that you can not only find in your kitchen cabinet, but also in your shower. They hold shampoos, conditioners, even food and food flavorings and additives, household cleaners, auto supply, art supply stuff, pesticides, other agricultural products. Some of these containers are used for fuel tanks for small engines like weed whackers, and chainsaws, and marine vehicles like boats.

BELTRAN: And how much PFAS can get into these products?

BENNETT: A lot. We worked with Dr. Graham Peaslee and one of his students Heather Whitehead at Notre Dame University. And they were finding levels of, routinely, about 60 parts per billion, which is 60,000 parts per trillion of PFAS. And that's how we measure it because it's so toxic, we look at it in parts per trillion. And we were finding levels of parts per billion. And Notre Dame and EPA both found that the PFAS from the containers would readily leach into the contents, even if it was just water.

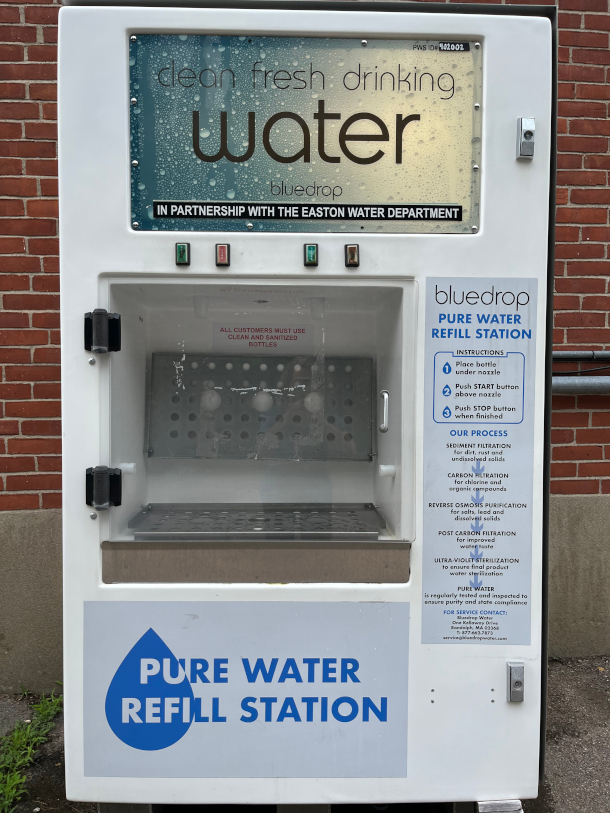

Filtration plants have been built in local communities to remove PFAS contamination from water. (Photo: Courtesy of Easton Department of Public Works)

BELTRAN: So, when the EPA realized it was the containers that were the source of PFAS, how did the agency react?

BENNETT: The agency initially reacted very well. And what they did is they contacted the manufacturer of Anvil and all the states, and they said if you have Anvil 10+10 In these fluorinated containers, we want you to discontinue use and hold them. The manufacturer of Anvil pulled back all of its product, they switched to a different type of container. So, EPA did the right thing. They prevented these pesticides that were contaminated with PFAS from being sprayed everywhere. But then they stopped. They just stopped with this one manufacturer, which really isn't fair, because there are many manufacturers who use these fluorinated containers, and it's not just pesticides. We realized after a couple of years that EPA wasn't going to do anything. So, we decided to sue Inhance, and now, unfortunately, you can't just sue a company for an EPA violation without first giving the government notice that you're going to do that, to give them an opportunity to do something. So, we filed our 60-day notice of intent to sue, and EPA filed an action against Inhance about a week before we did. So, we're actually both in court together now, suing Inhance. We are asking for similar but slightly different things. DOJ and EPA are asking for Inhance to cease the formation of these PFAS in their process until such time as EPA reviews the information that Inhance has submitted to them. PEER and CEH have taken that a step farther, and we've said, not only do we want you to stop until EPA reviews, we want you to shut it down entirely and forever. Because this is clearly an unreasonable risk to human health and the environment.

BELTRAN: And what alternatives exist to this fluorination process that ends up creating PFAS in these containers?

BENNETT: There are several, that's a good question. And the type of fluorination that Inhance does is called post-mold fluorination. So that's when the containers, the plastic containers are already formed, they're already blown. And then they're fluorinated. There's also a kind of fluorination called in-mold fluorination, where the fluorine gas is put in the hot molten plastic before the containers are formed. That seems to -- there needs to be way more work done on it -- but that seems to create far less or maybe even no PFAS. There's also glass and metal. And then there's another company out there that has another kind of barrier process that doesn't use fluorine at all, so there can be no potential for PFAS. So, there are many alternatives that companies could use other than this particular method that Inhance uses.

BELTRAN: What kind of authority does the EPA have to regulate and ban this practice?

BENNETT: They absolutely have the authority. The whole standard under TSCA, the law that covers this type of activity, is one of unreasonable risk. That's the legal standard. So, if anything presents an unreasonable risk to human health or the environment, EPA has the ability to stop what's going on. And in this particular case, we're talking about PFAS; one of the PFAS that are made in Inhance's fluorination process is PFOA. EPA said there is no safe level of this in our drinking water. And there are three exposure pathways for humans for getting PFAS into your system. You can ingest it through food or drink, you can inhale it, or it can be dermally absorbed. And so when they say there's no safe level of PFOA, and that it's a carcinogen, and here we have Inhance making containers that are leaching parts per billion into the contents, you have to realize that that is an unreasonable risk. So EPA has the authority and the duty to ban these chemicals and this process.

Until the PFAS filtration system was completed in Easton, Massachusetts, a PFAS-free water station was provided to the community. (Photo: Courtesy of Kyla Bennett)

BELTRAN: Kyla, how have you personally dealt with these findings?

BENNETT: It's really frightened me; I have always been somebody who's been concerned about contaminants in my environment, my husband and I try to have all non-toxic everything in our house. I only eat organic, I'm vegan, I don't use harsh chemicals anywhere. And in May of 2020, right at the beginning of the pandemic, I was diagnosed with a brain tumor, which was horrifying. I had two brain surgeries. I was in intensive care for a week in Boston. And after I came out, they tested me for genetic mutations to figure out why I had this very rare brain tumor. And it came out negative, I had no genetic mutations whatsoever. And the doctors told me that it was environmental. So, it's very personal for me, because I really feel that given how careful I tried to be, that it's very possible that the PFAS that I was drinking in my water was responsible for my brain tumor. And when I looked at the items that Inhance fluorinates, the bottles -- I used some of those shampoos, I've used some of those foods. I try not to have any plastic anymore, but as you probably know, it's really difficult to eliminate plastic from your life. But for me, this is very, very personal, for me and for my other friends in town who have cancer, my two dogs that died of cancer. It really upsets me that we were not given the choice to not buy these things. If I had known that these containers were fluorinated, had I known that they had PFAS, I would absolutely, 100%, not have purchased them. And even today, nobody knows. You can go to your CVS or your Shaws or whatever. And you can buy a bottle of shampoo off the shelf that is contaminated with PFAS and nobody knows. And to me, that's wrong, and it's horrifying.

BELTRAN: You know, Joe Biden's Cancer Moonshot plan seeks to deal with toxic chemicals that are linked to cancer, like PFAS. How do you think this moonshot plan will change how the US deals with chemicals?

BENNETT: I don't think it will. PEER is a client-driven whistleblower organization. We have clients come to us from EPA and a bunch of other federal and state agencies, even local agencies as well, everyone working in the environmental arena. And we had five clients from EPA's new chemical division come to us about three years ago now. And they revealed to us an extremely disturbing trend in the new chemicals division that showed that EPA is really working more for industry than it is for the public. The Office of Water at EPA is actually trying to do something -- in March of 2023, they came out with proposed rules to put limits on six PFAS in our drinking water, and they're pretty decent, low limits. But the problem is that the division of EPA that's dealing with Inhance's request to continue fluorinating is not the office of water, it's the new chemicals division. So, I don't think there's any hope of achieving President Biden's Cancer Moonshot program unless and until he gets this program at EPA under control. We cannot ignore this huge contamination problem of PFAS and still expect to get a handle on cancer.

Kyla Bennett is the Science Policy Director for PEER. (Photo: Courtesy of Kyla Bennett)

BELTRAN: And by the way, what has happened in your town since you found those high levels of PFAS in the water?

BENNETT: My town was absolutely great. At first, they didn't believe that we were contaminated, because there's no reason that we should be, but they tested, confirmed my results. And they were first in line, they went to Mass DEP, they said, we've got a problem. DEP gave us a grant to design our filtration system. $9 million later, the plant is about to come online in July, and I've been invited to the ribbon cutting ceremony. So, my town, my town was great. They handled it very, very well. They believed the science and they immediately acted. Before they started building the filtration plant, they immediately started handing out filters to people, and they have a PFAS-free water station at our water department, so anybody can go with a big jug, fill it up with PFAS-free water and take it home until the filtration plant is online.

BELTRAN: Kyla Bennett is the Science Policy Director at Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, or PEER. Thank you for joining us, Kyla.

BENNETT: Thank you so much for having me.

BELTRAN: We reached out to Inhance Technologies and EPA for comments but did not hear back in time for broadcast.

Links

The Guardian | “Plastic Containers Still Distributed Across the US are a Potential Health Disaster”

Learn more about Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER)

Learn more on the EPA’s strategy to prevent PFAS in plastic

Reuters “Environmental Groups Join Plastic Treatment PFAS Lawsuit”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth