A Call to Cool the Earth

Air Date: Week of July 21, 2023

The Arctic plays a critical role in the Earth’s climate system by reflecting heat back into the atmosphere and sequestering carbon in its frozen tundra. (Photo: Duncan Cumming, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Earth is choked by too much carbon in the atmosphere and running a fever that is only bound to get worse if we fail to restore its balance. Biologist Dr. George Woodwell explains to Host Steve Curwood why soaking up some of that carbon with the help of trees and plants is vitally important to life on Earth as we know it.

Transcript

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

Along with record-breaking heat around the world this July, it can be hard to breathe at times in the U.S., thanks to thick smoke from wildfires in Canada linked to global warming. And it’s a reminder of the basic science that the Earth itself breathes. Most of our planet’s landmass is in the Northern Hemisphere, and when the leaves take in carbon in our spring and summer, they leave roughly 600 gigatons of carbon in the atmosphere. And when the leaves fall and release carbon, they bring the total to about 700 gigatons. That atmospheric carbon regulates surface temperatures, and for millennia until the industrial age, temperatures and atmospheric carbon stayed in balance, as trees breathed the carbon in and out.

CURWOOD: But since we started cutting down whole forests and burning massive amounts of fossil vegetation in the form of oil, coal, and gas, we have thrown atmospheric carbon out of balance, and without enough trees, the planet itself is now choking on the excess. One symptom is the fever we call global warming, and this July has been the hottest ever.

CBS NEWSCASTER 1: Temperatures are expected to climb into the triple digits as a heatwave bakes the lower half of the country. Heat advisories are in effect from California through Florida.

CBS NEWSCASTER 2: We're at 12 straight days of temperatures of at least 110 degrees. And that could turn into 13 days. We'll have to see.

CURWOOD: And in Europe.

BBC NEWSCASTER: This heatwave has been named Cerberus. This is a three-headed monster that features in Dante's Inferno, and it's a very powerful heatwave that could cause temperatures to reach 48.8 degrees Celsius, and that could break a record for the hottest temperature ever to be recorded in Europe.

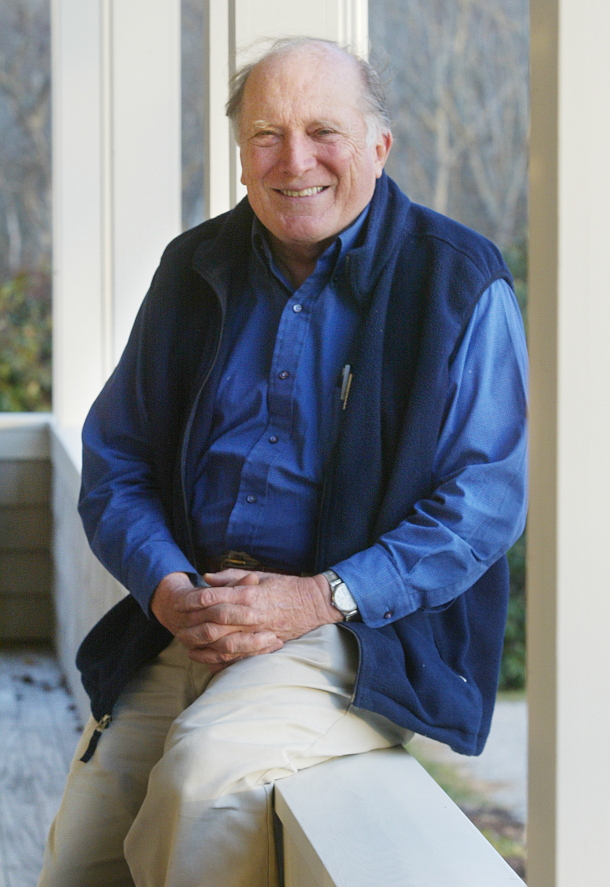

A recipient of many prestigious accolades from the Volvo Environment Prize to the Heinz Award, Dr. George Woodwell has fought to integrate scientific knowledge into public policy for over sixty years and served as a climate advisor in the Carter White House. He also played an influential role in drafting the UN Convention Framework on Climate Change Kyoto Protocol, and helped found the Environmental Defense Fund, and the Natural Resources Defense Fund. George Woodwell also founded the Woods Hole Research Center, renamed upon his retirement as the Woodwell Climate Research Center. (Photo: Daniel Webb)

CURWOOD: China has also broken heat records.

O’NEILL: And a warmer atmosphere is also able to hold more moisture before it precipitates out, as we have also seen this year.

MSNBC NEWSCASTER: Parts of Vermont experiencing their worst flooding since 1927. Worse than Hurricane Irene. Rescue teams worked overnight to find people stranded on streets that have been transformed into rivers.

PBS NEWSHOUR NEWSCASTER: In Northern India, officials say severe flooding from record monsoon rains killed more than 100 people in the last two weeks. In the capital, floodwater blocked roads, closed schools and swept away houses. The destruction left people struggling to cope.

O’NEILL: Because of lag times, today’s climate chaos is not a new normal. Climate disruption will continue to strengthen for years, even after we stop emitting carbon and cutting down trees, but we can limit how much worse it gets. The Paris Climate Agreement called for us to limit average global warming to 1.5 degrees centigrade. But already, according to the World Meteorological Organization, a fifth of the world’s population is experiencing at least one season over 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming, and the whole planet is not far behind.

Extreme weather is accelerating across the globe—and cooling the earth is more urgent than ever. (Photo: Russ Allison Lora, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, practically speaking, what’s to be done? One of the preeminent scientists who, early on, told us about how the whole world’s temperatures are linked to life on our planet is biologist George Woodwell, now in his nineties. Dr. Woodwell was a climate advisor to President Carter, helped start the Environmental Defense Fund and the Natural Resources Defense Council, and created the Woods Hole Research Center, which since his retirement is now called the Woodwell Climate Research Center. For years he warned that if we don’t save the trees and limit emissions, we could set off a feedback loop of global warming that would tap the huge amount of carbon stored in the Arctic’s permafrost. So, finding ways to cool the Arctic might help us while we finally take strong enough climate action. But how? We called Dr. Woodwell in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, to hear his insights and observations. Welcome back to Living on Earth.

WOODWELL: Well, thank you. It's a pleasure to talk with you, always.

CURWOOD: Why is the Arctic so important when it comes to managing climate disruption?

WOODWELL: The Arctic, of course, is a large area mostly covered by tundra, tundra plants, deep peat, organic matter, which have accumulated there for thousands of years. So it's a volume of carbon that's as large as the rest of the carbon held in forests and elsewhere in plants on Earth. An enormous pile of carbon, all vulnerable to decay, vulnerable to being turned into carbon dioxide and methane, warming the Earth.

CURWOOD: So the Arctic is warming nearly four times as fast as the rest of the planet. So, what will happen to the Earth's climate system if the Arctic continues to melt down this way?

WOODWELL: The Arctic is melting, and it's melting with, unfortunately, accelerating rapidity. Partly because the melting feeds on itself. The melting starts a pond. The pond is a black body, and it absorbs more heat, which causes more melting. As one pond is opened up, it quickly forms two ponds or a larger pond, and a big hole. And big pieces of organic matter, 10, 15, 20, 50, or a hundred feet long, and 15 or 50 feet wide, fall into the hole. Big chunks of carbonate fall away. And the products of the procedure are carbon dioxide and methane, largely. So, it's a feedback system. If we destroy or disturb the Arctic, it responds by producing more carbon, which destroys more of the Arctic.

Dr. Woodwell says we could stabilize global temperatures by protecting and establishing vegetation globally, which sequesters a substantial portion of the world’s carbon. (Photo: Mika Hiironniemi, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So sometimes, you've said we need to refreeze the Arctic. How do we do that?

WOODWELL: So, I have been arguing that the only spoken objective of all of these organizations looking at the Arctic, and looking at the climate problem, has to be how we cool the Earth. And we cool it of course, by reducing the amount of heat-trapping gas in the atmosphere. The heat-trapping gases are carbon dioxide and methane, largely. The carbon in the atmosphere has come largely, not only, of course, from our activities, our production of carbon dioxide. Fossil fuels is one, but also from our destruction of forests on a global basis. Forests destroyed, burned, produce carbon dioxide, and to some extent, methane, even though it's aerobic. The problem really is a balance between the Arctic and the rest of the carbon held on Earth, most of it in the vegetation of the Earth, south of the Arctic. The rest of the Earth contains about as much carbon as the Arctic itself. And that pool of carbon can be increased. We can build up the carbon storage, for instance, in forests, globally, which is substantial, and balance it off against the carbon accumulation in the atmosphere that is melting the Arctic. We have to reestablish forests where they've been diminished or abandoned. And we have to build stores of carbon in soils and plants, globally. So the vegetation of the Earth is of critical importance now. That's a fair mission. It's already the mission of many organizations, and most governments in some form, but the intensity with which we go at that topic has to be doubled and redoubled beyond that. It has to be the business of the world to restore the human habitat and the stability of that habitat.

CURWOOD: Now, there are some schemes kicking around to try to blow more moisture over the Arctic to get more Arctic sea ice and everything. What do you think of those schemes?

WOODWELL: Oh, I think it's essential that we restore the sea ice if we can. Restoring the ice and the ice in the Arctic Ocean turns the Arctic Ocean from a black body in summer, absorbing heat from the sun and warming itself further, to a reflective white body of ice, which reflects that heat back into space. Hard to say how to make ice in the Arctic if it doesn't make itself. We don't have an easy mechanism. But it's all a part of the transition toward a stable Earth. And it's our business, without any question.

CURWOOD: George Woodwell is the founder of the Woods Hole Research Center, now known these days as the Woodwell Climate Research Center, in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. Dr. Woodwell, thanks so much for taking the time with me today.

WOODWELL: Delighted to talk with you.

Links

Woodwell Climate Research Center | “Home Page”

Woodwell Climate Research Center | “Dr. George Woodwell”

Volvo Environmental Prize | "2001 Laureate: George M. Woodwell ]”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth