Salt Water in the Mississippi

Air Date: Week of October 6, 2023

A shipping boat glides up the Mississippi River across from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers' New Orleans District headquarters off Leake Avenue on Sept. 15, 2023. (Photo: Halle Parker, WWNO)

Amid widespread drought, salty water from the Gulf of Mexico is slowly seeping up the Mississippi River towards New Orleans, Louisiana. Halle Parker of public radio station WWNO explains the situation, how it's linked to climate change and possible solutions to Host Jenni Doering.

Transcript

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

The great Mississippi River moves an enormous amount of water south from the central and Eastern US, but not as much this year thanks to drought conditions. Usually, the freshwater that flows south in the Mississippi pushes back salt water as the river nears the Gulf of Mexico, but now that salty water is slowly seeping upriver towards New Orleans and contaminating water supplies. Experts say that freshwater species should be fine, but for human’s high levels of salt in drinking water can worsen high blood pressure. President Joe Biden has declared a federal emergency at the request of the Louisiana Governor, freeing up federal funds to address the situation. Here to tell us more is Halle Parker, who reports on the environment for public radio station WWNO in New Orleans. Welcome to Living on Earth Halle!

DOERING: So what are experts saying about what could happen if people actually drink this water?

PARKER: So that's one of the things that's pretty crazy about what's going on down here is just how much uncertainty there still is. Right now, there isn't any sort of like effect for any places that are highly populated, you know, like New Orleans, or Jefferson Parish, the metropolitan area around New Orleans. But people down in Plaquemines Parish, which is a more sparsely populated area to the south have been dealing with this for a while, right? They actually saw a lot of salt in their water for months on end, and it was like around 1600 parts per million. And just to put that into perspective, 250 parts per million is what the EPA, the Environmental Protection Agency, says is when you start, you know, to actually be able to taste that salt in the water. So 1600 parts per million is like six and a half times that.

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Col. Cullen Jones, who commands the New Orleans District, provides an update on his office's measures to address a "saltwater wedge" moving up a historically low Mississippi River during a news conference on Sept. 15, 2023. (Photo: Halle Parker, WWNO)

DOERING: Wow, that's a lot.

PARKER:Yeah, It's a lot of salt. At that point, no one's drinking the water or even for some people, like you can use it to brush your teeth, but you're not really going to it really just doesn't taste very good. But something that our officials are really grappling with is trying to understand like at what point at what level of salt, do we need to worry about corrosion? And also does that level of salt that's an issue does that change over the amount of time that that salt water is around.

DOERING: And of course, corrosion of lead pipes was something that was happening in Flint, Michigan, and led to a lot of the high levels of lead in that water. To what extent could this happen in this case?

Plaquemines Parish President W. Keith Hinkley describes how his office has coped as saltwater moving up the Gulf of Mexico has contaminated drinking water for much of his parish this summer during a news conference on Sept. 15, 2023. (Photo: Halle Parker, WWNO)

PARKER: Yeah. So the risk is for real, it's a very real risk down here. So our mayor, Mayor LaToya Cantrell, told us that at least from their initial analysis, which is still ongoing, they're still mapping out and trying to figure out where exactly lead pipes are, how many they have, but they've already come across at least 50,000 lead pipes in New Orleans. And Jefferson Parish, that metro area close to us doesn't even know yet, they haven't started studying how many lead pipes they have. So it's really this concerning and also still open question for people. And you know, that's part of why what's happening with the saltwater intrusion is so concerning for people down here. There's just so much uncertainty around what's going to happen.

DOERING: Yeah and like you said, officials aren't necessarily sure exactly where this tips over into something that could damage infrastructure. But I imagine that the risks of that are great enough and the consequences are great enough that we don't want to really get close to that.

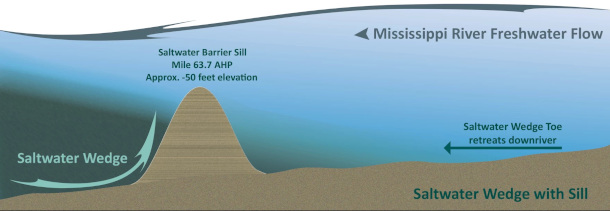

A graphic depicting what a saltwater wedge looks like, how it interacts with freshwater, as well as the sill, or underwater barrier, constructed by the Corps in July 2023. (Photo: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers)

PARKER: Exactly, yeah, no one wants to see lead pipes start corroding, and leaching into water, we already have issues with lead in our soil. So we don't need any more exposure down here. I know that over in Jefferson Parish, they've already started to at least begin introducing like a type of phosphate, interestingly enough into their water system. to try to avoid and prevent corrosion from happening. And that is something that we're waiting to hear if New Orleans is looking at as well. So there might be some options here for avoiding corrosion, depending on how bad the salt level gets here.

DOERING: Yeah, it's good to hear that there are some solutions, potentially, in some ways to protect the infrastructure. What other solutions to this problem of saltwater moving up the Mississippi River are officials proposing?

An aerial view of barges and container ships traveling down the Mississippi River in April 2022. Industrial plants line the riverbanks. (Photo: Kezia Setyawan)

PARKER: Yeah, really good question. So, you know, if you go talk to these officials, they'll say that they're looking at anything and everything. But right now, there's kind of like a multi pronged approach happening. So different agencies are doing different things like we have the Army Corps of Engineers coming in to really support of course, the whole region. But they're going to be especially helpful for some of the smaller water treatment plants in this area. They're able to provide things like water barges where you chip in fresh water from up higher in the river that's not being affected by this saltwater wedge, and take it down to those water treatment plants that are being affected, so that they have some fresh water to use to make sure that they have enough to dilute the water in their system so that we are not able to taste that salt, that additional salt in the water. And then beyond that, aside from those smaller water treatment plants that have the option of maybe getting water from a larger plant or from a water barge or from a reverse osmosis unit, our larger plans in New Orleans and in Jefferson Parish, they're really looking to just make a new pipeline. Like move where they're taking water from or getting at least some of their water from and moving that higher up the river similar to that water barge solution. And using those new pipelines to pull in water from a safe area of the river and bring it back down to feed into those really large systems that like to compare some of these systems are only pumping out you know, like 4 million gallons of water a day, which you know, sounds like a lot but then you think about these gigantic plants in there pumping like 140 million gallons of water a day.

DOERING: So what about farms and agriculture? How might the saltwater wedge affect those?

Halle Parker reports on the environment for WWNO's Coastal Desk. (Photo: Courtesy of Halle Parker)

PARKER: Yeah, so, saltwater, especially saltwater intrusion has actually been affecting, you know, South Louisiana for a while now, usually doesn't mean that it's coming up the Mississippi River, typically that's in like actual groundwater in the water table rising just because a lot of this region is sinking at a faster rate than other areas across the country. And so when that happens, the saltwater has the opportunity to move up in the soil. So I just want to make it clear that this isn't a new issue that farmers down here are dealing with. But they are of course incredibly concerned about the saltwater wedge, because where are they supposed to get the water to water their crops? Normally, that would be coming from the Mississippi River to help irrigate, especially down in Plaquemines Parish where a lot of farmers are citrus farmers. And I've gotten there after hurricanes. And if you get, you know, a strong surge from hurricanes of saltwater in the area, and it sits around, all of that salt starts to seep into the soil. And if you don't get some rain, or if you don't have a way to flush it out, then that can actually start poisoning your crops, you know, like they're tolerant to salt up to a certain extent, but you need to be able to get that salt out and refresh the soil. And if they're not able to get you know, that fresh water from the river that makes it really difficult for them, they have to try to find another source of fresh water to keep their crops alive. So it's a big concern for them.

DOERING: Halle, what are experts saying about the role that climate change might play in all of this?

PARKER: Yeah, that's a super important question. So really, when you think about why the saltwater intrusion is happening this year, you think about the drought that's happening. And not only the drought this year, but the drought that happened last year, too. These are two events that are compounding on top of each other. And they're the types of extreme weather that are going to become more likely and more frequent due to climate change. And so when I spoke with John Sabo, who is the director of Tulane University's ByWater Institute, he said that really we shouldn't expect this to become a new normal where it happens every single year but it is something that we should be prepared to have happen more frequently and more often. And that's partially because of drought, like I mentioned, but also because of sea level rise. And so you know, as the Gulf of Mexico continues to rise that could make it easier for it to start to intrude upward.

DOERING: Halle Parker reports on the environment for public radio station WWNO in New Orleans, Louisiana. Thank you so much, Halle.

PARKER: Thanks for talking with me, Jenni.

Links

Bloomberg | “They Dredged the Mississippi River for Trade. Now a Water Crisis Looms”

WGNO | "U.S. Army Corps of Engineers gives update on timeline of saltwater intrusion in Louisiana"

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth