A Native Perspective of the First Thanksgiving

Air Date: Week of November 17, 2023

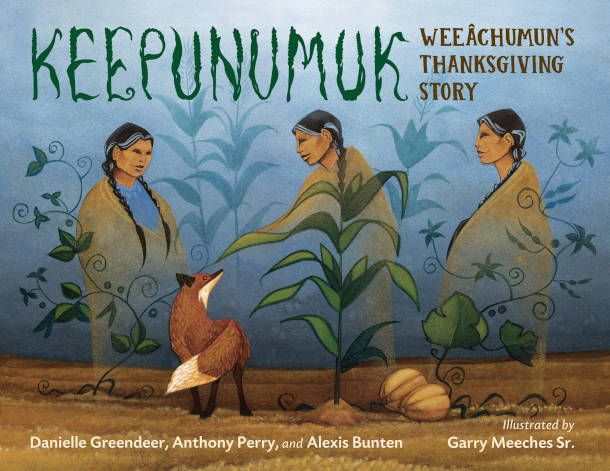

Keepunumuk: Weeâchumun’s Thanksgiving Story is a picture book that attempts to teach young children a new, more inclusive, Thanksgiving story. (Photo: © 2022 by Garry Meeches Sr.)

The story of the “first Thanksgiving” that persists in American culture often stereotypes Native peoples and sanitizes what happened to them as white settlers dispossessed them of their lands. A picture book written and illustrated by Indigenous authors offers a new story of the “first Thanksgiving” that centers the Three Sisters crops. Author Tony Perry joins Host Jenni Doering to discuss the inspiration for Keepunumuk: Weeâchumun’s Thanksgiving Story and share ideas for creating a more inclusive holiday.

Transcript

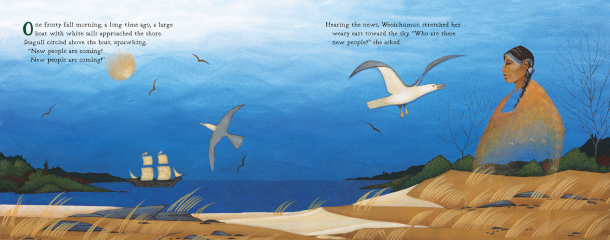

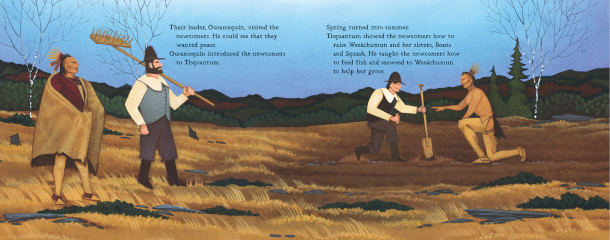

O’NEILL: “I love your garden this time of year,” said Maple. “Me, too. What shall we pick for lunch?” N8hkumuhs asked. “How about crab apples?” Maple suggested. “No! Chokecherries!” Quill shouted. “Those are both good medicine,” N8hkumuhs said. “How about some weeâchumun, as well?” “Yes!” Maple replied. “She is such a good big sister to Beans and Squash.” “The Three Sisters! They grow together,” Quill added. “You’re right. They feed people all over Turtle Island,” N8hkumuhs said. “And they have many stories to tell.” “Can you tell us a story?” Quill asked. “How about the time Weeâchumun asked our Wampanoag ancestors to help the Pilgrims?” N8hkumuhs replied. “The first Thanksgiving?” Maple asked. “Some people call it that,” N8hkuhums said. “We call it Keepunumuk, the time of harvest. Here’s what really happened.”

DOERING: Those are the opening lines of Keepunumuk: Weeâchumun’s Thanksgiving Story. Weeâchumun, or Corn, is the protagonist in this tale. It’s for young readers so the violence white Europeans brought against Native Americans soon after the time of the Pilgrims isn’t directly in the story. But it does reference the “day of mourning” which is what some Native American people now call Thanksgiving Day. And the story was written and illustrated by Indigenous authors who are descended from the first peoples on this continent. Author Tony Perry joins me now. Welcome to Living on Earth!

PERRY: Thank you. Thank you for the opportunity.

DOERING: You are one of three authors on this book. Can you tell us a little bit about your specific role in creating it?

Tony Perry, one of the coauthors of Keepunumuk, is a citizen of the Chickasaw Nation and currently lives in the U.K. He hopes that the book will create a new default narrative for the Thanksgiving story. (Photo: Courtesy of Chickasaw Press)

PERRY: Absolutely. Actually, I'm going to explain kind of how this book came about because we each ended up having a role. So just to introduce myself, I am a citizen of the Chickasaw Nation. I grew up in Oklahoma, but I live in England now. Our co authors and our Illustrator come from a very broad range of native traditions, but we are all native creators. Danielle Greendeer is Mashpee Wampanoag so one of the a citizen of the people whose ancestors met the new comers. And Alexis Bunton is Alaska Native, Unangan and Yu'pik. And our illustrator, Gary Meeches Sr., is Anishinaabe. And so the story began, actually through work that Alexis Bunton was doing. She had started an initiative or was participating in initiative called decolonizing Thanksgiving. And a lot of this came from the Thanksgiving meal and the idea of Thanksgiving that we take for granted now, right, the story that I certainly grew up with, was around pilgrims coming across looking for a new life meeting a few friendly Indians and they had, you know, who helped them out, they ended up having a feast, and everyone was happy. And that's the story that we have. And so Alexis has done a lot of work trying to unpick some of that story. Pointing out, for example, that it's a myth that came out after the Civil War by a publisher named Sarah Josefa Hale, who had persuaded Abraham Lincoln to have a day of thanks. That's where the idea that so many Americans have of Thanksgiving was really born. And what jumped out to me is that there is so much hard work done by people like Alexis, as well as Danielle and many others, to try to almost reteach this holiday, right, to read to say, look, here's what really happened. What do you think about it? And Keepunumuk takes this at a different approach. Instead of trying to unteach and reteach a story, it's about creating a new story. So if the story that so many Americans know is itself a story, why couldn't we create a new story that creates a new default narrative? And that's what we set out to do. So Alexis and I worked together, trying to think about what this could look like, you know, we talked about it with Danielle and she just said, right? Well, I'd love to work with you. Let's do it. So the three of us started working on the text. Danielle knew Gary Meeches Sr. And so all this came through about a collaboration and a common vision of creating a new narrative, a more inclusive story. But it came through having that common vision and everyone bringing their own perspectives to this with again, with native peoples at the heart to make this possible. And as a result, we have Keepunumuk.

Danielle Greendeer is one of the coauthors of Keepunumuk. She is a citizen of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe, the tribe which first encountered the pilgrims back in the 1600s. While all the authors and the illustrator are Indigenous people, her particular background was key in making sure the book accurately represented the Wampanoag. (Photo: Matt Cosby)

DOERING: And why is it so important to have indigenous people themselves telling these kinds of stories?

PERRY: Ultimately, because this story is about indigenous peoples. It's about the first peoples that were here, and their voices are not have not been really heard. And it's important to note the role of native peoples because again, they were they were there. They were the ones that were frankly, the center of this story, really, and also what happened afterwards. There is a story of frankly, genocide and of oppression of native peoples, whether it's massacres that happened to the Wampanoag people, King Philip's War that happened about 70 years after where the descendants of the pilgrims return their thanks for having that settlement there by massacring Wampanoag peoples. Then you go further on, you've got the removal of native peoples from their lands as European Americans started to want more space. So my ancestors were among those who were removed from their homeland, as more and more settlers occupied our lands. Going back to the Wampanoag people, just in the last administration, the Mashpee Wampanoag tribe were fighting for their very recognition when a president decided to undo a decision that recognize them. And so this went to the highest levels. Thankfully, they have that recognition. These fights to recognize that we were the first peoples on the continent, continue our fight for our identity. And I think it's important to emphasize that we were there. We have survived and are still here and are thriving.

DOERING: So many of us spend time with young children over Thanksgiving. As we talk to young, especially non native kids about Thanksgiving, how can we be honest about the genocide of indigenous people and colonization in an age appropriate way?

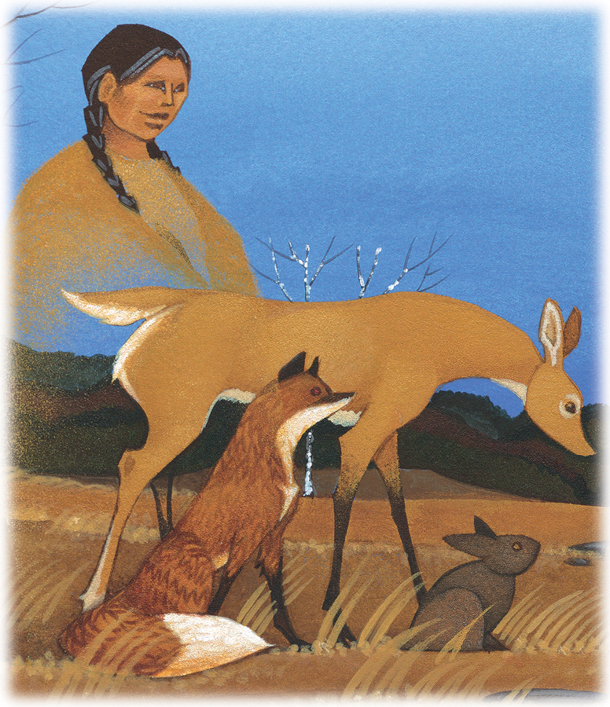

In the book, the animals and plants come together and agree to send the First Peoples to help the pilgrims. (Photo: © 2022 by Garry Meeches Sr.)

PERRY: That is a very good question and, and it's hard. I would say that, as you say age appropriate, I think is the key part to this. So in the very beginning of it for the earliest readers, I think it's important to note about the native peoples that were there in this story, and also doing more to think about, well, who are native peoples where do you live now? On what land do you live? Right? Who were the original occupants of that land? So I think that's the starting point of it, and learning more about who those people are, and maybe some of their traditions. So I think that's probably the first entry point to it. For older children, I think that the conversations do become different. They become deeper. That is where you start getting into the conversations around colonialism, decolonialism, about what we can do about it, recognition and also inclusivity and respect that America certainly today is a far more diverse country than it was, say 30 years ago, as I was going through school. I think it's important to recognize that and by recognizing that there are many American stories. We as Native Americans are certainly one and play an important one. But it's right there in the fabric with African Americans, Asian Americans, others who have come and settled and some of the struggles and triumphs that they have had.

DOERING: So the story is told through the perspective of corn, who is called Weeâchumun. Why did you decide to have corn narrate the story?

Although the book does highlight the First Peoples’ perspective, the main character of the book is Weeâchumun, corn. (Photo: © 2022 by Garry Meeches Sr.)

PERRY: Well, there's a couple of reasons for this. Number one is that corn plays a vital role in the culture of many native peoples that is in the United States going into Mexico, Central and South America. Corn, in fact, was a plant that was created by native peoples. Native peoples had actually created what we know as corn today out of blades of grass, which is a rich story in and of its own right, and plays a central role in the heart of cultures of native peoples, many native peoples today. Beans and squash grow very closely with corn. Native peoples call them the Three Sisters. Native peoples are quite diverse. We're not a monolithic group. So some native peoples will have three sisters, others may have four and some five, but corn, beans, and squash is a pretty universal tradition.

DOERING: And the three sisters are somewhat universal because of the ecology of how those plants grow together. Is that right?

The book features the Three Sisters: beans, corn, and squash which are prominent among many Native American traditions. The three plants are dependent on each other to grow plentifully. (Photo: © 2022 by Garry Meeches Sr.)

PERRY: That's right. That's exactly right. Corn grows first. In native traditions, corn will grow first. It provides structure, and then the beans end up wrapping around the corn. But beans also feeds corn because corn takes nitrates from the soil, and beans actually added in. And then squash, the third sister will grow on the outer sides and keep other plants from taking up space and that sort of thing. So it's their own harmony. So that was important for us. Number two, we also felt that by telling the story through corn, but also other plants and animals, as opposed through just another retelling well, but maybe from a native point of view, we felt like this would spark more thought and more discussion, rather than just a story from quote the other side, which, unfortunately, is how it would be perceived if we just read it as, "Well, here's what happened with Wampanoag people, and through their eyes, and so on" So instead of pitting one against another, we thought, well, let's let's de center this a little bit, and provide what is really a more universal story because we all depend on the ecology, on the world around us. And it shapes what options that we have and how we live our lives. So we felt like this would be a more inclusive way of telling the story, helps people think broader than even just Thanksgiving itself to think about how we live in the world today. And as well as being able to give a new perspective to Thanksgiving and hopefully give room for thought.

DOERING: What advice do you have for how we can celebrate Thanksgiving in a way that respects and honors indigenous peoples?

While the book does steer away from the popular Thanksgiving narrative, it does show First Peoples helping the Pilgrims learn to survive. (Photo: © 2022 by Garry Meeches Sr.)

PERRY: That's a good question. And I think the first part of it is to use the holiday as a way to think about the native peoples where families are living, right. So for families having Thanksgiving, it's an opportunity to ask those questions around well, "Whose land was this originally? Who were the native peoples that live or lived in this land?" And trying to understand a bit more about them, about their cultures and traditions, and what's happened to them today and happening to them today. The book includes backmatter that describes where the Wampanoag people are in the United States, also their storytelling traditions. It offers activities, so trying a Wampanoag tradition of giving thanks through a spirit plate. So basically leaving behind a meal outside you know, and giving thanks to the world. And also a recipe to try Nasamp, which is a traditional Wampanoag dish, as well. So there's a bit of activity and learning as well that tries to set the scene for the book and where it fits in the wider world. I think it's also important to consider the role of native peoples not just on Thanksgiving, but across the year because of the role that they played in the American story, both past and present, and learn more about some of the challenges that they're facing. And also the triumphs. So looking at, you know, native representation and maybe buying books or watching films that involve native characters, that center their stories. So those are different things that you can do.

DOERING: Tony Perry is a citizen of the Chickasaw Nation and one of the authors of Keepunumuk: Weeâchumun's Thanksgiving Story. Thank you so much, Tony.

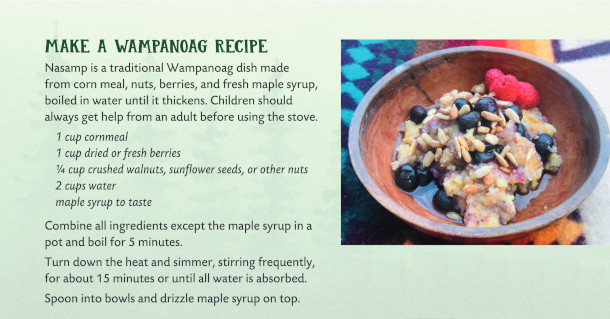

The Keepunumuk authors have included a recipe for 'nasamp', a traditional Wampanoag dish. (Photo: Courtesy of Danielle Greendeer, Anthony Perry, and Alexis Bunten)

PERRY: Thank you.

CURWOOD: Our studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston are on the traditional, ancestral and unceded Pawtucket and Massachusett First Nations land, with Wampanoag traditional lands just south of here around Cape Cod. By the way, Nasamp, the traditional Wampanoag dish isn’t hard to make. You boil corn meal, berries, nuts or seeds in water for a few minutes, then let it simmer until the water is absorbed. Drizzle some maple syrup on top for a sweet finish. For the complete recipe and more check out our website, loe dot org.

Links

Learn more about the book and its authors

Explore ways to decolonize Thanksgiving

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth