Climate Deception

Air Date: Week of January 19, 2024

The Global Climate Coalition was a lobbying organization created by a group of fossil fuel companies to spread climate denial. One of its primary objectives was to block the United States from signing the Kyoto Protocol. (Photo: Marianne Muegenburg Cothern, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

When scientists began to warn in the later half of the twentieth century that burning oil, gas, and coal could bring severe consequences for our planet, they touched a nerve in the powerful fossil fuel industry. In this second installment of our series on climate change disinformation, historian of science Naomi Oreskes and Host Steve Curwood dive into how the fossil fuel industry infiltrated the political sphere and scientific community to block climate action.

Transcript

DOERING: When scientists began to warn in the later half of the twentieth century that burning oil, gas, and coal could bring severe consequences for our planet, they touched a nerve in the powerful fossil fuel industry. In Part 1 of our series on climate change disinformation, we talked with Harvard historian of science Naomi Oreskes about the strategy and messaging behind the efforts of the fossil fuel industry to dupe the public into believing that climate science was uncertain. Today, we continue the chat between Naomi Oreskes and Host Steve Curwood to dive further into how the oil and gas industry infiltrated the political sphere and scientific community to block climate action.

ORESKES: The Global Climate Coalition was an organization put together by a group of fossil fuel companies, including nearly all of the major oil and gas companies in the United States like ExxonMobil, Chevron, Sunoco, also major coal producers like Peabody Coal, and also other groups whose businesses relied on cheap energy, so for example, Alcoa aluminum. This was very characteristic of the sorts of activities that we've seen repeatedly over the last 30 years; to create an organization that on the surface appears to be independent of the fossil fuel industry. So it doesn't say fossil fuels or industry in the title, Global Climate Coalition, maybe even to make it seem like it's a grassroots organization. So coalition seems to involve, you know, the sort of thing you imagine grassroots groups, public social movements, and to make it seem as if they care about the climate. The Global Climate Coalition, if you didn't know anything about it, you might think that that was a group who was trying to stop climate change. But in fact, what they were trying to stop was action to address climate change. And this group was put together for the specific purpose, and we know this because we have the documents, to prevent the United States Congress from ratifying the Kyoto Protocol.

CURWOOD: So just what exactly did the Kyoto Protocol propose?

The Kyoto Protocol, adopted by the UNFCCC in December 1997, committed signatories to binding carbon emissions reductions. (Photo: UNclimatechange, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

ORESKES: The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, which President George H. W. Bush had signed on behalf of the United States, committed the US to taking action to stop, the famous phrase is, "dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system." But the 1992 convention is a statement of principle. It says we intend to do this, but it doesn't say how. The Kyoto Protocol says how. We're going to have binding emissions cuts. And those cuts will begin with the world's wealthy nations, what they call the so- called Annex 1 nations, which were the rich, highly industrialized countries like the United States, Canada, the European Union countries, Japan, Australia. These were all the countries that had become rich by burning fossil fuels. And at that time, most of the emissions in the atmosphere, something like I think 80%, had been produced just by about 10 or 12 countries. So the focus was on these countries that had industrialized early. And the idea was that this was fair, that this would be just, because we were the countries who had made the problem, and that once those countries were on board, then the second phase would be to think about developing nations like China and India. And then the third step would be to think about poor countries and how they could be helped to develop without fossil fuels. So it was actually a very logical and a very equitable approach. It really embodied a kind of environmental justice concept into the framework. The Global Climate Coalition launched major campaigns to scuttle that.

CURWOOD: So what tactics did the Global Climate Coalition use to block the Kyoto Protocol? And I do remember running into somebody from that group in Kyoto at the time, wondering what they were up to. What did they do?

ORESKES: Well, they worked on a number of fronts. So one front involved public opinion. They didn't want the public to be mobilized to demand action on climate change. And so one way they did that was to try to convince the public, that is to say to convince us, that the science around climate change was highly uncertain. And therefore it'd be foolish, it would be premature, to pass any kind of laws or sign any treaties. And so they ran advertising campaigns to persuade us that the Kyoto Protocol was unnecessary, that it would cost a lot of money. They also tried to influence newspaper editors and people like yourself, radio and television people, to send them materials suggesting that climate change was, we didn't really know, there was no scientific consensus, and again, that it would therefore be premature to sign on to the Kyoto treaty, because the Kyoto Protocol committed the signatories to binding reductions in carbon dioxide emissions. When that was killed, that was the last time that we ever had any serious international proposal for binding limits on greenhouse gas emissions.

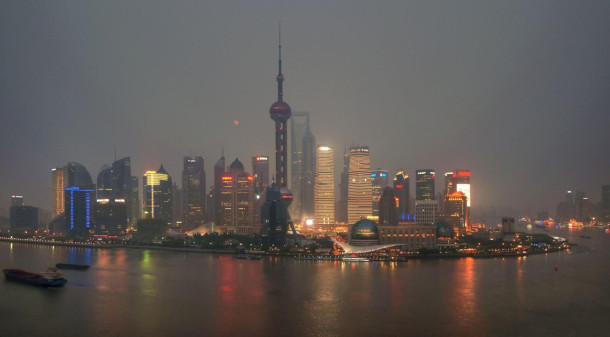

The Global Climate Coalition claimed the Kyoto Protocol would be unfair, since developed nations like the US were expected to cut their carbon emissions before developing nations like China. (Photo: Mariusz Kluzniac, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: By the way, what role did the Global Climate Coalition play in what's known as the Byrd-Hagel Amendment, and how that affected politics at the UN negotiations?

ORESKES: They played a very large role. So as I just said a moment ago, one front was to influence public opinion. But the other front equally, if not more important, was to influence Congress, to persuade American politicians not to agree, not to sign on to the Kyoto Protocol, to persuade American lawmakers that this was unfair, that it was unjust. It was an early version of the "what-about-ism," well, what about China, to say that somehow this would be unfair for us to have to cut our emissions if China and India weren't also cutting theirs, and that it would hurt the American economy. And so they persuaded both Democrats and Republicans, essentially to reject it. And the rejection took the form of the Byrd-Hagel Amendment. That was named after Robert Byrd, a Democrat from West Virginia, a big coal state, and Chuck Hagel from Nebraska, a big oil and gas state. And it essentially said that the United States should not sign any international treaty that would be economically disadvantageous to the United States. And it was targeted at Kyoto. And that passed the Senate, I believe it was 95 to zero?

CURWOOD: Unanimous, in any case.

ORESKES: Unanimous, no opposition whatsoever. And once that passed, Kyoto was effectively dead. And so the Clinton administration never even tried to bring Kyoto to a vote in Congress, knowing that it was at that point a lost cause.

CURWOOD: Now, talk to me about the other important fossil fuel lobbying groups that have gained power over time. How do they influence political will, do you think?

Prof. Oreskes says the Inflation Reduction Act is the first time in US history that any law has been passed by the US Congress to address the climate crisis. She credits this delay in part to “massive organization” by pro-fossil fuel interests against previous laws addressing the climate crisis. (Photo: Prachatai, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

ORESKES: Well, I think they've influenced it a lot, because we've seen that every time there's been an attempt to have a meaningful law passed in Congress, we've seen massive organization against it. And the Inflation Reduction Act, which was just passed recently under the Biden administration, is the first time in US history that any law has been passed by the US Congress to address the climate crisis. And this is in the 30 years since we signed the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. So we've had 30 years where Congress has failed to make good on the promise of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. A lot of this work was done not by the fossil fuel companies themselves, but by what they call third party allies. So other groups who appear to be independent, but are not. And many of these are think tanks. So in our work, we've documented the role of a number of think tanks, and there are literally scores of these groups. And at one point, I tried to put together a slide to list them all, and it got to be the font had to be so tiny, you couldn't read it. But we've documented at least 100 of these organizations in the United States and elsewhere. They include groups like the Heartland Institute, who have directly attacked scientists, groups like the Competitive Enterprise Institute, the American Enterprise Institute, the Cato Institute, and many, many more. What they all have in common is that they all promote free market principles. They all promote the idea that we shouldn't need the government to intervene in the marketplace, and therefore we shouldn't act on the climate crisis. Now some of them make that argument in a way that, I would say is honest, but wrong, in my opinion, which is to say, we don't need the government to do anything. The market will solve it on its own. I think we have plenty of evidence to show that that idea is incorrect. But I wouldn't say, it's not exactly disinformation. But many of them have pursued disinformation. And by that, I mean, they have issued reports, had conferences, workshops, written opinion pieces in which they claim that the science is unsettled. Or they claim that we don't really know what's causing climate change, or they claim that the cost of fixing it will be greater than the benefit. And these things are false.

CURWOOD: Now, of course, another way that the fossil fuel industry has protected its position here is through campaign financing, to get politicians in office who will go along with the story that they're telling. Talk to me about how that practice began, and why it is so important when it comes to understanding the influence of the fossil fuel industry in today's world?

Some fossil fuel companies directly fund some politicians on Capitol Hill through campaign financing. (Photo: Elliot P., Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

ORESKES: Well, in a way you can think of that as the third front, which is the direct funding of politicians. And as we all know, money plays a big role in American politics. And it's played an even bigger role since the Citizens United Supreme Court decision, which essentially removed any limits on the amount of money that individuals or groups could give to politicians or people running for office. We know that many hundreds of millions of dollars have been funneled by the fossil fuel industry to candidates for public office and people holding public office. Senator Sheldon Whitehouse of Rhode Island wrote a piece a few years ago where he showed that if you look at the people in Congress who are the major recipients of fossil fuel funding, not one of them has ever voted in support of a climate bill, ever. So the link is pretty obvious. The fossil fuel industry doesn't want us to have policies that would limit the use of fossil fuels because that would cut into their profits. And so they fund candidates, in part to make sure that their interests are represented on Capitol Hill.

CURWOOD: To what extent is this phenomenon of money in politics when it comes to climate change elsewhere on the planet? I mean, we have quite an open and lengthy political season here. What about the other democracies around the world?

ORESKES: Yeah, that's a great question. I haven't really studied the role of politics in other democracies. But as you alluded to a moment ago, we have this extremely lengthy campaign process in the United States, where there's essentially no limit to when the campaign can begin, and when people can begin spending money. Most European democracies don't permit that. The campaign has a finite amount of time. And there's a finite amount of time during which you can spend money on things like advertising. It doesn't eliminate the role of money in politics, but it controls it to some extent. So we don't see quite the same degree of industry capture as we see in the United States. But of course, you know, money plays a role in politics everywhere.

Sultan Al-Jaber, the CEO of oil company Adnoc and President of COP 28, claimed there was no scientific basis for the 1.5-degree Celsius target set by the Paris Agreement. (Photo: Mark Field, COP28, Présidence de la République du Bénin, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: To what extent do you think the difference in political systems allowed Europe to proceed with its own version of the Kyoto Protocol, whereas the United States simply completely opted out?

ORESKES: Yeah. I think we've seen in the last 30 years, in many different ways, not just in terms of climate, but other issues, too, and the ways in which parliamentary systems, they're not perfect, but overall do a better job of representing the interests of people, in part because minority parties can earn seats and have a voice in parliament. So for example, in Germany, the Green Party has never been the dominant party in German politics, but it's been a significant minority voice. And because people have to build coalitions, often in a parliamentary system, you'd have to create a coalition in order to govern, the Green parties have been able to influence policy in Europe in a way that they have not in the United States.

[MUSIC: Roy Hargrove, “Stasbourg / St Denis” on Earfood, Groovin’ High]

BELTRAN: Naomi Oreskes is a historian who has authored books including The Big Myth: How American Business Taught Us to Loathe Government and Love the Free Market. We’ll have more from her conversation with Host Steve Curwood in just a moment. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Roy Hargrove, “Stasbourg / St Denis” on Earfood, Groovin’ High]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Roy Hargrove, “Stasbourg / St Denis” on Earfood, Groovin’ High]

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

We’re back with more from Host Steve Curwood’s chat with history professor Naomi Oreskes on the influence of the fossil fuel industry on international politics. The long campaign to delay and slow action on climate change has included infiltrating the scientific community.

CURWOOD: Let's talk about the IPCC now for a moment. That's the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. You're a historian of science, Naomi. And this organization was created by scientists to look at the question of climate disruption. I think it's 1988. To what extent did the fossil fuel industry play a role in how climate science from the IPCC was put together and then told to the public?

In the United States many agricultural carbon emissions are tied to beef production. (Photo: Anders Gustavson, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

ORESKES: So the answer to the IPCC is very interesting, because it's a quite unusual organization historically, because it's a hybrid organization of science and governance. So the IPCC was created as a joint venture between scientists through the World Meteorological Organization, an international scientific group, and the United Nations Environment Programme. So it was a conscious, deliberate attempt to bring the science and the politics together, so that scientists could give information to policymakers so that politicians could make good, scientifically informed decisions about this really important issue that we were facing. And I think in the early years, people were extremely optimistic that even though they knew there would be industry resistance, they didn't think it would be that big a deal. And we know something about why because we've interviewed many of the scientists who are involved. The IPCC was modeled in many ways, on something called the Ozone Trends Panel. That was a group that was organized to address the ozone hole. And it had been very successful in informing policy. And it had provided the scientific basis for the Montreal Protocol, which was an equivalent kind of protocol to protect stratospheric ozone. Industry had pushed back against it, but it had been managed. And the Montreal Protocol was this very, very successful piece of science based policy that successfully protected us from stratospheric ozone depletion. So that was the model. It was a success story. And scientists thought, well, we did it for ozone, so we could do it now for climate. But what they didn't count on was that there would be a much larger, much more extensive, and frankly, much nastier industry response. And I think part of the reason for that is, well, first of all, fossil fuels are more important. I mean, the chemicals that created ozone depletion were useful chemicals, but the whole world economy didn't depend on them. And only one company made most of those chemicals. It was DuPont. When DuPont's own scientists said, hey, these chemicals are really, really bad, this is potentially threatening the existence of life on Earth, DuPont did the right thing and said, okay, find us substitutes, and their scientists did. But the fossil fuel industry behaved very differently. Instead of saying, okay, we need to find substitutes, they essentially said there are no substitute. And so we will fight to the death to defend fossil fuels. And so right from the get-go, there was much more industry opposition. The other thing that industry did was they put their own people inside the IPCC. So there were scientists who worked in industry, for example, scientists who worked for ExxonMobil, who actually became participants in the IPCC process. Now, why did IPCC do that? Well, they were trying to do the right thing. They were trying to be open minded, and inclusive and capacious and say, yeah, industry scientists have something to say. There's no reason why we should exclude them. And so they actually welcomed these industry scientists into the process. And you can see, especially in the early reports, industry scientists who are coauthors on some of the key chapters. But what we now know, in hindsight, and again, from interviews with scientists, that at least some of the scientists worked to weaken the reports. They played the role of the skeptic, the contrarian, the naysayer. And so the IPCC reports, were, in my opinion, softer or weaker than the science actually warranted at that time. I think there are a few reasons for that. But I think one of the reasons is the role of industry scientists who were inside the IPCC, pushing back against firmer, stronger conclusions.

Local changes in public transport, electric vehicle infrastructure, and building codes can still make a difference in global carbon emissions, Prof. Oreskes says. (Photo: Maria Ekland, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: So the most recent Conference of the Parties of the UNFCCC, had an oil executive as president of it. And next year, there's a former oil executive who will be in charge in Azerbaijan, although he's officially I guess, the Minister of the Environment there. What do you make of those developments?

ORESKES: Well, it's very sad, and it's actually painful to talk about. I have many good friends who are active in the COP process. I know a lot of people who are still committed to it, who feel that we can't give up. But I think the reality and we're seeing it very clearly, as you said, this will now be two meetings in a row run by fossil fuel executives. Essentially, the whole process has been captured by the fossil fuel industry. So Al Jaber, who headed up the COP 28 has just completed, stated shortly before the meeting began, that there was no scientific basis for the 1.5 degree threshold that we always talk about. Well, I mean, that was just preposterous. And, you know, you didn't know whether to laugh or cry at a claim like that. But I live in a world where people are constantly saying to me well, but you know, climate change denial, that's a thing of the past, right? Nobody really denies the reality of climate change. And then Al Jaber says there's no scientific basis for 1.5. And it's a continued rejection of the solidity of the scientific evidence, the solidity of the scientific data. And we're also seeing a politics of distraction. So they began the meeting by doing something very clever, announcing some steps to restrict methane emissions from oil and gas production. Well, that's not a bad thing. I mean, as long as you're still producing oil and gas, you definitely would like to reduce the methane leakage from oil and gas wells. But it's a small piece of the whole picture. And if it distracts attention from the larger fact, which is that you're still burning oil and gas, you're still producing oil and gas, you're still selling oil and gas, then it becomes the equivalent of the tobacco industry pushing low tar cigarettes.

CURWOOD: Before you go, Naomi, what do you think, is to be done? I mean, how do we move beyond the grasp of the special interest of the fossil fuel industry to keep burning this stuff, and at the same time burning the planet, and move into a future that we can sustain?

ORESKES: Well, it's obviously very difficult. But I think one thing that people can do as individuals, and I often like to talk about this, because this is such a depressing story, that this is kind of one piece of this that's empowering, which is that we can change the way we eat. And we don't have to depend on Congress because we can make our own choices. So we know from various studies that if you think about all the greenhouse gas emissions that are going into the atmosphere, it breaks down roughly 60/40. Sixty percent have to do with using fossil fuels, and the other 40% has to do with the land with agriculture, deforestation, and other forms of land use changes. A big piece of those emissions come from animal agriculture, particularly in the United States, beef. And so we have a lot of agency about food. You know, this is a small good news story: if you eat less red meat, it's good for the planet. But it's also good for you, it's good for your body. So that's a win win. And it's cheaper, too. The other thing that we can do is to lower our gaze. And by that I mean to work more locally, particularly on the state and local level, because a lot of attention has been put into the COP process, the big international agreement, a lot of attention has been put into the federal government. And of course, it would be great if we could get international cooperation. And it would be great if we could get Congress to act meaningfully. But in the absence of that action, there's a lot we can do on the state and local level. And especially if you think about fossil fuel use, fossil fuel use is tied up with economic activity. And most economic activity takes place in cities, and most American cities are progressive. You know, we often talk about red states and blue states. But that's not actually what we're looking at. What we're really looking at is blue cities and red rural areas. Most people live in cities, most economic activity takes place in cities. So if we can get cities to work more aggressively, and many cities are, but to amp up those efforts, with better building codes, you could have city or state based carbon pricing systems, do more to build up electric car infrastructure in cities, do more to build up public transportation. So I think there's a lot we can do on the state and local level. There's a lot we can do as individuals. In my own town of Carlisle, we recently passed a stricter building code. And I spoke at town meeting to say exactly what I just said today. This is something that we can do here, tonight, that doesn't depend upon the federal government. So let's do it. And I'm proud to say that in Carlisle, we did.

DOERING: That’s Harvard Professor of the History of Science, Naomi Oreskes, speaking with Living on Earth Host and Executive Producer Steve Curwood.

Editors Note: In the interview the Byrd-Hagel Resolution was incorrectly referred to as the Byrd-Hagel “Amendment.”

Links

Listen to Fossil Fuel Deception Part I

The Guardian | “The Forgotten Oil Ads That Told Us Climate Change Was Nothing.”

Global Climate Coalition Advertisements

Global Climate Coalition Documents

Advocating Inaction: A Historical Analysis of the Global Climate Coalition

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth