US-Mexico Water Treaty

Air Date: Week of May 31, 2024

The Rio Conchos feeds alfalfa and pecan production in Chihuahua, Mexico. Farmers and politicians in Chihuahua have opposed additional water deliveries to the United States, with several farmer protests starting in 2020. (Photo: Luke Hosty, Inside Climate News)

Amid extreme drought affecting Rio Grande tributaries, Mexico is struggling to make water deliveries to Texas as required by an 80-year old treaty. Martha Pskowski is a reporter with Inside Climate News and spoke with Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran about how the situation is linked to climate change and farmer livelihoods in both the US and Mexico.

Transcript

O’NEILL: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering. Along the dry southern border, water is a precious resource that the United States and Mexico have had to share. They’re guided by a treaty dating back to 1944, decades before scientists understood how climate change could make water an even scarcer resource in the region. Now the two countries are renegotiating the treaty at a moment when extreme drought means Mexico is struggling to make water deliveries to Texas from Rio Grande tributaries. With farmers’ jobs on the line in both the U.S. and Mexico, negotiators are hoping that recent history doesn’t repeat itself. In 2020, tensions among Chihuahuan farmers who didn’t have enough water for their crops boiled over into violence. One demonstrator was killed when the National Guard opened fire. And the water crisis has become a campaign issue in Mexico’s June 2nd presidential election. Living on Earth producer Paloma Beltran asked Martha Pskowski, a reporter with our media partner Inside Climate News, to explain how the treaty is supposed to work.

PSKOWSKI: So the 1944 treaty is signed between the U.S. and Mexico, and it governs the three main rivers that are shared between the two countries. So that's the Rio Grande, the Colorado River, and the Tijuana River, which is smaller. So on the Rio Grande, Mexico sends water to the United States, because one of the biggest tributaries of the Rio Grande is called the Rio Conchos, and that's in Mexico. And then on the Colorado River, the U.S. sends water to Mexico, which is downstream in that case. So on the Rio Grande, the 1944 treaty requires that Mexico sends 1.75 million acre feet of water to the United States. And that's over a five-year cycle. So that comes out to an average of 350,000 acre feet of water each year. But Mexico has to hit that target at the end of the five years. So those are the main terms of the 1944 treaty.

BELTRAN: And negotiations on the treaty need to be finalized by October 2025. How's that looking so far?

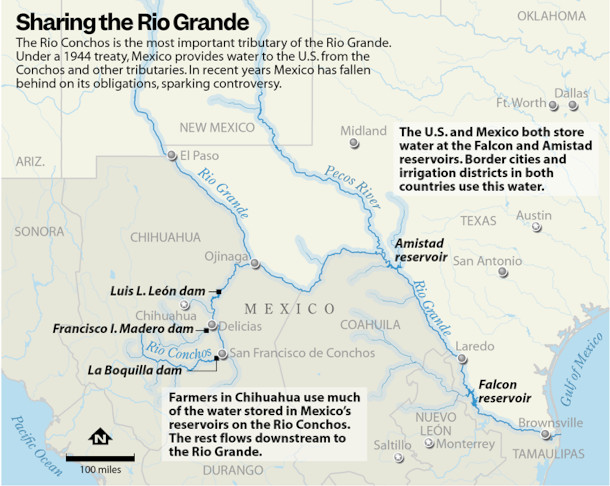

The above map shows the various rivers, dams, and reservoirs in Northern Mexico and Southern Texas, including: the Rio Grande, Rio Conchos, Pecos River, Luis L. León Dam, Francisco I. Madero Dam, and La Boquilla Dam. (Image: Inside Climate News)

PSKOWSKI: At this point, we're in the fourth year of the five-year cycle, and Mexico has sent about one year's worth of water. So there's only a little over a year left, and they have about four years' worth of water to send to the U.S. So it's going to be very difficult for them to meet that target just based on the amount of water they can store. So they're probably not going to hit that target next year.

BELTRAN: And how is climate change complicating the fulfillment of this treaty?

PSKOWSKI: Right. So for the provisions on the Rio Grande, the headwaters of the Rio Grande are in Colorado. So the river comes out of the mountains there and runs down through New Mexico into Texas. But when we see the Rio Grande in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas, in the part that reaches the Gulf of Mexico, most of that water is actually coming from tributaries in Mexico. And for both the headwaters of the Rio Grande in Colorado and those tributaries in Mexico, the ongoing drought is impacting the runoff, the amount of snowmelt we see. So the hotter temperatures and less rainfall is impacting the Rio Grande and its tributaries, which then makes it more difficult for Mexico to meet its requirements under the treaty.

BELTRAN: Yeah. And you know, millions of people depend on these three rivers, the Rio Grande, the Colorado River and the Tijuana River. I think it's probably more than 50 million people that rely on the water from these rivers. How are these droughts, these impacts from climate change, affecting people on both sides of the border? What are some of the stories you heard?

La Boquilla Dam on the Rio Conchos in Chihuahua, Mexico. (Photo: Omar Ornelas, Inside Climate News)

PSKOWSKI: Right, so we're seeing the same issues, whether it's in Texas or Chihuahua. Irrigation, agriculture in these states relies on getting a lot of water from the rivers to irrigate crops like pecans, cotton, citrus, so farmers feel a lot of the first impacts just having less water for irrigation. So they're reducing the amount of acres they plan, or changing crops, but it also impacts cities and towns. You know, the Rio Grande provides water for places like Laredo, McAllen and the Mexican state of Tamaulipas. So those communities in the Rio Grande Valley are also facing potential water shortages this summer and looking into what other sources of water they might have access to just because they're getting—the water they're getting from the Rio Grande is getting less and less reliable. So this isn't just about farmers. It's really everyone who lives in these watersheds is touched by the issue.

BELTRAN: And we've been talking about agriculture. But how has biodiversity and wildlife been impacted by both the execution of the 1944 water treaty and also the drought faced throughout western U.S. and northern Mexico?

PSKOWSKI: It's a huge issue. You know, the Rio Grande where it meets the Gulf of Mexico, we've seen it drying for the first time in recent years, for the first time in a while, where the river doesn't always reach the Gulf. And there's also sections like the one in between El Paso and Presidio, Texas, that goes through Big Bend. Historically, that part of the river has dried a lot, but now it basically runs dry every year. So that just means all of the aquatic species, the birds, the plants, they don't have that water that really gives that ecosystem life. So I know there's concerns that we can't just view the water as this resource to be moved around for agriculture. We need to think about it holistically. But there is a lot of work to do to make sure we have those flows consistently, so all of the creatures that rely on the river can, can flourish, because there has been a lot of loss of biodiversity along the river in Texas, and also the rivers in northern Mexico.

The Rio Grande River passes through Colonia Victoria neighborhood in Nuevo Laredo in Tamaulipas, Mexico and Laredo, Texas, USA. (Photo: Miguel Angel Omaña Rojas, Wikipedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

BELTRAN: In 2020, several Mexican farmers protested against the state of Chihuahua sending their reservoir water to Texas. What pushed them in that direction? Why did they do that?

PSKOWSKI: Right. So this was in the fall of 2020. Mexico was coming up on the deadline to send water to the United States, and they were preparing to send water from a dam and reservoir called La Boquilla, which is in Chihuahua. And farmers in Chihuahua were upset because they wanted that water for their agricultural production. So there were protests at the reservoir in opposition to Mexico sending that water to the United States. And, you know, I've done some reporting and talked to some of those farmers and, you know, there's just this feeling of, we don't have enough water to maintain the status of production that we're used to, and why should we send this water to the United States? So there are concerns that that kind of protest could happen again as Mexico tries to meet the treaty target in the coming year.

BELTRAN: And in your reporting, you talked to community members of La Boquilla in Chihuahua. Can you tell us some of their stories? What are their concerns? What did they tell you?

In September 2020, farmers in Chihuahua fought against the Mexican National Guard to protest sending their water to the US. (Photo: Lalof3, Wikipedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

PSKOWSKI: Right. So the way that water is managed in Mexico is different from the U.S. So there's a national authority called Conagua. So that's the National Water Commission. And they make the decisions about how to allocate water from rivers like the Conchos in Chihuahua. A lot of the farmers and also politicians in Chihuahua feel that this federal agency isn't fully representing their interests, they don't feel like they've really had a seat at the table to figure out how to address this situation. I was reporting last summer in some of those communities around Delicias. And, you know, people really rely on agriculture there. And if they aren't able to continue that lifestyle, you know, a lot of them said, like, we're gonna have to move into cities, we might go try and work in the U.S. And there's also a big population of farmworkers in that area, a lot of whom are indigenous, the Rarámuri. So you know, this whole economy is revolving around irrigation agriculture. So when they have to cut back their water use, that has a whole cascade across the community. So those are some of the concerns they have with how the federal government is handling the situation. That's more so their issue than, you know, like, being angry at the U.S. They think Mexico needs to deal with this differently.

BELTRAN: And through your reporting, you talked to several water experts and advocates from both Texas and Chihuahua. What are some of the solutions they're recommending or they're advising on?

PSKOWSKI: Well, these negotiations about the treaty, there's just some specific terms and parts of the treaty that there's different interpretations on each side. So one of the big issues is the treaty gives Mexico the option to roll over its obligations to a second five-year cycle if the country is in extraordinary drought. So Mexico has used that option a few times in the past. So if they haven't sent the water at the end of the five years, they basically get another five years. But there's no shared definition of what extraordinary drought means. So the U.S., they don't want Mexico to revert to that option every single time. So clearing that up is going to be important. But I think also just looking long term at what's the most sustainable way to continue agriculture in these areas. So I talked to an irrigation manager in the Rio Grande Valley and he said, it's really hard when farmers are already having a difficult year, to make the investments, to make a change. So in South Texas, the sugar mill already closed down, because it's just not viable to grow sugar anymore. So helping farmers think long term about what are going to be crops that they can grow without as much water, that's really important, but it's not something, you know, everyone has the means to do when they're in the middle of a crisis. So I think that long-term planning is really going to be important going forward.

Martha Pskowski covers climate change and the environment in Texas for Inside Climate News from El Paso. (Photo: Courtesy of Martha Pskowski)

BELTRAN: What's at stake here? What are the repercussions if the terms of the treaty are not fulfilled in time?

PSKOWSKI: Right, it's—I think everyone wants to avoid repeating the situation in 2020, when there were those big protests in Chihuahua. So the U.S. and Mexico have been negotiating to reach a new agreement. So far, that hasn't been signed. So you know, if this conflict drags out into 2025, it's really hard to say where it might go. You know, generally the U.S. and Mexico have a very close relationship diplomatically. You know, trade, there's so many issues that these two countries work on. So I don't think anyone wants the water treaty to become a source of conflicts. But coming up with a solution is going to take some creativity. And you know, the treaty has lasted for 80 years, so it's been very resilient through a lot of changes. But both the political situation and the environmental situation that we're experiencing right now are raising issues of how this treaty can continue to be effective into the future. So I think on both sides, everyone's hoping for a diplomatic solution and that there can be a resolution before the end of next year and kind of avoiding any protests and that sort of reaction.

DOERING: That’s Martha Pskowski of Inside Climate News speaking with Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran.

Links

Inside Climate News | “The Other Border Dispute Is Over an 80-Year-Old Water Treaty”

Reuters | “Parched Texas Growing Season Looms As US, Mexico Spar Over Water Treaty”

The Washington Post | “A Water War Is Brewing Between the U.S. and Mexico. Here’s Why.”

Circle of Blue | “Can U.S and Mexico Secure Water Supplies in Shrinking Rio Grande?”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth