From the History Books

Air Date: Week of June 7, 2024

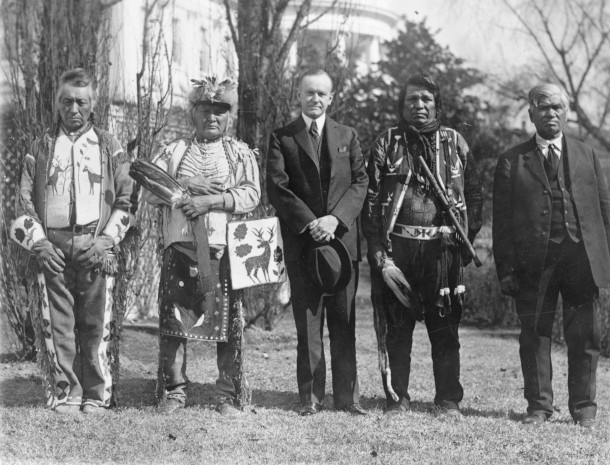

President Coolidge (center) standing with four members of the Osage Nation at a White House ceremony after signing the Indian Citizenship Act in 1924. (Photo: National Photo Company Collection, Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

This week, Host Steve Curwood and Living on Earth contributor Peter Dykstra mark 100 years since the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act. Though a step towards equality Native Americans had to wait until 1957 to secure nationwide voting rights. Also, it’s 60 years since the commissioning of the pioneering submersible ALVIN, which went on to discover the unique ecosystems around hot deep-sea vents.

Transcript

CURWOOD: On the line now from Atlanta, Georgia is Peter Dykstra, a contributor to Living on Earth and the master of the history books. Hey, Peter, what do you see for us today?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. June 2, 1924, 100 years ago, the U.S. Congress passed the Indian Citizenship Act. After 300 years of conquest and genocide, it hardly reflected a huge change in white America's attitudes toward Native America. But maybe a slight reversal of U.S. attitudes. Slight indeed, the law left the issues of voting rights for many Native Americans to individual states. American Indians did not have nationwide right to vote until 1957. And of course, poverty and all sorts of other ills have continued to plague Native American reservations and communities all over the United States.

CURWOOD: Indeed, and isn't it curious that one can have an American passport and say, an Irish or an Israeli passport for a number of years. And yet, it took until 1957 for the First Nation people to have the right to vote. But hey, as some say, the arc of the universe bends towards justice. Maybe too often too slow for, for many of us. Hey, Peter, what else do you see in the history books at this point?

DYKSTRA: June 5, 1964. Significant in a couple of different ways. My mom's birthday, of course, but also the 60th anniversary of the commissioning of the submersible vehicle Alvin by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute. Its first significant mission didn't occur for two years, when Alvin dived to explore the possible site of a hydrogen bomb lost by a U.S. plane off the coast of Palomares, Spain. But Alvin became a mainstay of deep ocean exploration and discovery, and is celebrated as such ever since.

CURWOOD: Yeah, I mean, Alvin found those hot vents, those hydrothermal vents deep in the ocean, where there are living systems, deep sea ecosystems that exist without sunlight and are based on chemosynthesis. It's kind of amazing. And by the way, who was Alvin, anyway?

Swimmers recover ALVIN after a dive on the “Mountains in the Sea Expedition” in 2004. (Photo: NOAA, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

DYKSTRA: Alvin is a mash-up of the name of oceanographer Allyn Vine. He was a big player back in the 1960s in oceanographic research in places like Woods Hole and Scripps on the West Coast. And Alvin memorialized his name forevermore.

CURWOOD: All right. Hey, thanks, Peter, for those stories. Peter Dykstra is a contributor to Living on Earth, and we'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Steve, thanks a lot. We'll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth webpage. That's loe.org.

[MUSIC: Yoyo International Orchestra, “Yellow Submarine” The Love Songs of The Beatles – Instrumentals Volume 2, YOYO USA, Inc.]

CURWOOD: Next week on Living on Earth, Juneteenth is just around the corner, and we are looking at African American pioneers like Madam C. J. Walker. She developed a line of cosmetics and hair care products for Black women and became the first female self-made millionaire in America.

BUNDLES: Well, she was really very much a motivator. And while, you know, hair care is the, that's the—she made hair care products, she was really, in some sense, a motivator. So, she made these products. She knew that women needed these products for hygiene reasons, for hairstyling, versatility. But I think over a period of time, she began to see the hair care products as a means to an end. Part of it was, yes, we accomplished this, you know, we make hair care products, we make women have better hygiene, they feel better about themselves because they feel better about the way they look. But it also became a platform for women to become economically independent. One woman wrote to her, and she said, you have made it possible for a Black woman to make more money in a day selling your products than she could in a month working in somebody's kitchen. And then as she had her first convention in 1917, and she brought together 200 women who had been domestic workers, who had been farm workers, even a few schoolteachers, she saw that what they really needed was education and economic independence. And she told them at the convention in her keynote, “As Walker agents, I want you to understand that your first duty is to humanity. I want others to look at us and realize that we care not just about ourselves but about others.”

CURWOOD: Tune in to Living on Earth next time to hear about Black hair, joy and resilience as we get ready to celebrate Juneteenth.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth