An Urgent Juneteenth Call for Climate Solutions

Air Date: Week of June 21, 2024

ExxonMobil’s Baton Rouge Refinery along Louisiana’s “Cancer Alley.” (Photo: Jim Bowen, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

Generations of Black Americans have faced racism, redlining and environmental injustices, such as breathing 40 percent dirtier air and being twice as likely as white Americans to be hospitalized or die from climate-related health problems. So the quest for racial justice now must include addressing the climate emergency, writes Heather McTeer Toney in her 2023 book Before the Streetlights Come On: Black America’s Urgent Call for Climate Solutions. She joins Host Steve Curwood in part one of their conversation.

Transcript

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is the Living on Earth Juneteenth holiday special. I’m Steve Curwood.

[MUSIC: The Golden Gospel Singers, “Oh Freedom” on A Cappella Praise, Blue Flame Records]

CURWOOD: On June nineteenth of 1865 enslaved African Americans in Galveston Texas finally got the news that more than two years earlier President Abraham Lincoln had already emancipated three and a half million enslaved people in the Confederate States in rebellion against the Union. By the way, it would take until nearly the end of 1865 for slavery to be outlawed by the 13th Amendment of the Constitution in the remaining slaveholding states like Kentucky, Delaware and New Jersey that had not left the union. But on June 19th of 1866, a year after union troops rode into Texas with the news of freedom, the now free folks in the Galveston area started the Juneteenth tradition of an annual celebration and now it’s a national holiday. And though we’ve come a long way since then, true freedom and equality for all have yet to arrive. Generations of Black Americans have faced racism, redlining and environmental injustices, such as breathing 40 percent dirtier air and being twice as likely as white Americans to be hospitalized or die from climate-related health problems. So, the quest for justice now must include addressing the climate emergency, writes Heather McTeer Toney in her 2023 book Before the Streetlights Come On: Black America’s Urgent Call for Climate Solutions. Black kids were often told to “Get home before the streetlights come on,” words of caution to avoid situations that could endanger young Black lives. Now Heather McTeer Toney is saying black America, along with everyone else needs to take climate action before the darkness of climate catastrophe descends. The former mayor of Greenville, Mississippi, Ms. Toney served as the Southeast Regional Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency under President Barack Obama. And she is now the Executive Director of Beyond Petrochemicals. Welcome back to Living on Earth Heather!

MCTEER: Thanks so much. It's great to be back. Thanks for inviting me back.

CURWOOD: So one of the examples that really opened my eyes to the challenges of both government and officials, when they try to make changes is the North Birmingham story that you tell in your book. You were Region 4 administrator for the EPA, you visited North Birmingham at one point and then you went back. Tell us that story please.

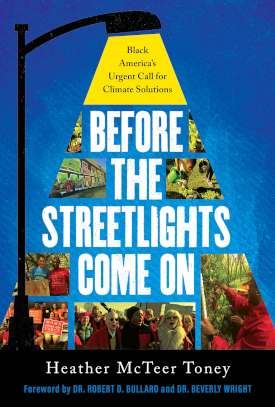

Heather McTeer Toney’s “Before the Streetlights Come On: Black America’s Urgent Call for Climate Solutions.” (Image: Courtesy of Heather McTeer Toney)

MCTEER: So North Birmingham reminded me a lot of my own hometown of Greenville, Mississippi. I was born and raised in the Mississippi Delta, and a community full of love but also full of its own challenges and struggles. So when I was appointed to be regional administrator for EPA in the Southeast, Alabama was part of the community that I served. And North Birmingham, Alabama had been fraught with environmental injustices of a local coke plant and that's not Coca Cola, like the product we drink, but coke which is a byproduct of coal, and burning of coal. And this particular community had been inundated with years of air pollution, so much so that you could feel it in the air and on the street. People talked about how it left a, almost like an itchy filmy residue on the skin. And they had been for a long time asking for help to not only clean the land but also to recognize the impacts of this pollution on their health. There was a high rate of cancer, a high rate of airborne illnesses, asthma, impacts that really were directly related to the air pollution, but nobody, it really recognized it or acknowledged as such. So when I came into the North Birmingham community, it was incumbent upon me as a part of the Obama administration, but also as a part of this community, as an African-American woman born and raised in the south seeing what look like myself, to be as much help as I could be in this space in this moment. So together, we worked on how we could reclaim the land through Brownfields funding. How we could encourage solutions that were created that weren't necessarily connected to environment that people wanted to see done, like revitalizing businesses and schools that have been in that space for a long time. What I did not know was that the state of Alabama and I think historic, and systemic racism that is prevalent throughout our country was going to be just as strongly involved in that space, even with or without me. And there was a very active investigation that was taking place in North Birmingham around bribery; in fact, there were elected officials that were indicted during that time period, all to keep this community from receiving the justice that they really deserve. So it was eye opening to me that it really spoke to the struggles that communities, particularly communities of color across this country face when dealing with environmental justice.

CURWOOD: Yeah, you write in your book that you first rolled through there in the parade of black SUVs, befitting a high federal official, but somebody approached you there and said something.

MCTEER: Yeah, there was a Mr. Smith, who lived in that neighborhood. And I remember we had a community meeting. And he came up to me at this community meeting and I will never forget, he was holding a picture of his deceased loved ones, his family members and he said to me, "So what are you gonna do? What you're gonna do this different than all these other folks" You come up in here, which SUVs, but what are you going to do?". We sort of toured that day, and he came back to me separate, he said, "I want you to do something for me, I want you to come back here, and I don't want you to come back here with all your people. I want you to come back by yourself because they cleaned up for you today, they cleaned up all of the pollution and they cleaned up the streets for you, they washed it all down". He said "but madam administrator you come through here, when ain't nobody looking and then you tell me what you saw". And I did, one trip I was driving in my car coming from my home, going back to Atlanta, and I drove through the back way to get in to the neighborhood and he was absolutely correct. The streets were covered with a film. I stopped and I put my hand like on a fence and I could wipe my hand and could see residue on my hand from what had been blowing over from this coke facility. I went to his house knocked on the door he wasn't at home [LAUGH]. But people know what's happening in their spaces, and we should listen to them more. And that was my experience of understanding the historic legacy of housing discrimination and social injustices that had impacted places like North Birmingham. How real they were today and how much they connect it to environmental justice. And that's what I wanted to write about. I think that was the importance of telling that story in my book, because it connected the dots between legacy pollution, legacy discrimination, and how and why we are experiencing disproportionately environmental injustice in black and brown communities today across this country.

Sugarcane fields in front of the Marathon Garyville refinery in St. John the Baptist Parish, adjacent to St. James Parish, Louisiana. Enslaved African Americans once toiled to grow sugarcane on plantations, and today petrochemical plants are replacing agriculture in the region. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

CURWOOD: There's an area colloquially called cancer alley. It's this 85-mile stretch of land along the Mississippi between Baton Rouge and New Orleans and I think there's over 200 petrochemical plants and refineries and now communities there have been speaking out about the plethora of health issues, thinking of cancer and miscarriages that are associated with the constant exposure of chemicals from these plants. And a lot of people living there are descendants of slaves and in fact, some of these plants are next to slave gravesites. What does this tell us about the historic legacy of slavery and environmental justice in the United States that this highly toxic area is a cradle of descendants of slaves?

MCTEER: There is an irrefutable connection between the footprint of enslavement and the travesties that have been placed upon, from African and the enslaved, that is directly related to environmental injustice is that we experience today. Joy and Jo Banner, both sisters that have been working on a project called The Descendants Project in cancer alley I think have expressed this beautifully in their work of protecting the community in the space that they come from, that was subject and still is subject to being the site of a grain elevator. And they have been successful in making sure that the site itself is listed on the eleven most endangered sites by the National Historic Preservation Trust. And the reason they were able to do that was because they were able to show not only is this an 11-mile stretch along cancer alley, that has not yet been inundated by industry that needs to be protected, but also because their ancestors are buried in this space. Every other space along cancer alley, has been impacted negatively by air pollution, land pollution, water pollution, because of this industry, and this industry sits in the exact same footprints that plantation set in all along the coast of Louisiana. There's an Atlantic article that showed this footprint where you could overlay the boundaries of plantations in Louisiana and put on top of that the existing facilities and an almost matched identically. Do you know how scary that is? Let's just think about that for a second, the places where Joy and Joe Banners great, great, great grandfathers were enslaved are the same places that their aunts and cousins work at today, just for a different industry. That really has captured people falsely, because we talk often about the jobs that are brought to these communities be don't talk about the cost. And our communities I think as a whole are being moved to now be a part of the solution and action phase that we're in so that we do not allow industries to continue repeating the same messaging and stories that have negatively impacted our homes.

Heather McTeer Toney is an American politician, environmentalist, and attorney. In 2014, Toney was appointed as a regional administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency for the Southeast region by President Barack Obama. She is now the Executive Director of Bloomberg Philanthropies’ Beyond Petrochemicals Campaign. (Photo: Courtesy of Heather McTeer Toney)

CURWOOD: By the way those plantations in Louisiana were sugar plantations. And sugar made people fabulously wealthy in the way that say the internet boom did. It was a path to a lot of money, although as many as a third of the enslaved persons sold down the river from places like Kentucky and Virginia in the North would, succumb in the frequent yellow fever epidemics.

MCTEER: Yes.

CURWOOD: So, we're speaking at the time of Juneteenth. What can we learn about the petrochemical industry and its impact on environmental justice as we move forward with the celebration?

MCTEER: The beauty of Juneteenth and the fact that our United States of America acknowledges this as a federal holiday. Enslaved Africans were in Texas when they got that message. so that they were no longer enslaved but we're now subject to the same rights and liberties is the rest of us across the United States that had been freed. And today in Texas, this is where there is an extraordinary amount of petrochemical facilities that are already seated, but also a place where people are being falsely told that this will be an improvement to their lives, versus the reality of the chemical impacts, the environmental injustices, the travesties that take place to the human body by putting more chemicals into this space. So, what better time than Juneteenth to help and let our folks know that we are all free and we can be free from the petrochemical industry. We don't need more of the industry to be placed in communities, particularly communities of color, but we certainly don't need more plastics in our body. We don't need more economic disparity and we don't need to be told lies about how this is going to make our lives better when we have history that tells us that it is not.

Links

The Atlantic | “Louisiana Chemical Plants are Thriving off of Slavery”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth