Chaos in the Climate System

Air Date: Week of September 20, 2024

Greenhouse gases are heating the atmosphere. A warmer atmosphere holds more moisture, which increases the amount of rainfall during precipitation events. (Photo: Kritzolina, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Catastrophic flooding in Africa, Europe and Asia is linked to changes in the jet stream and warming of the Arctic. University of Pennsylvania climate scientist Michael Mann joins Host Steve Curwood for a discussion about why climate disruption is making extreme weather events much more likely, and how the world can still avert the worst outcomes of runaway climate change.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Catastrophic floods like those inundating West Africa and Central Europe are sometimes called “acts of God,” disasters that are out of our hands. And in this year that is likely to be the warmest in human times, extreme weather events have become so common, many people are shrugging off these signs of climate disruption with the same sense of inevitability. Yet our fingerprints are undeniably all over the changes to climate systems of the Earth, and we keep making things worse. Science tells us though, that people still can make a difference. Here to present some of the physics behind the explosive growth of severe rain and flooding this year around the world, and what he calls a bit of good news, is Michael Mann. He is a distinguished professor in the Department of Earth and Environmental Science at the University of Pennsylvania, and on the line now from Philadelphia. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Michael!

MANN: Thanks, Steve, always good to be with you.

CURWOOD: Great to hear you. So today, would you please walk us through how climate change affects the water cycle? I mean, to what extent can we attribute these catastrophic floods in West Africa and Central Europe to climate disruption?

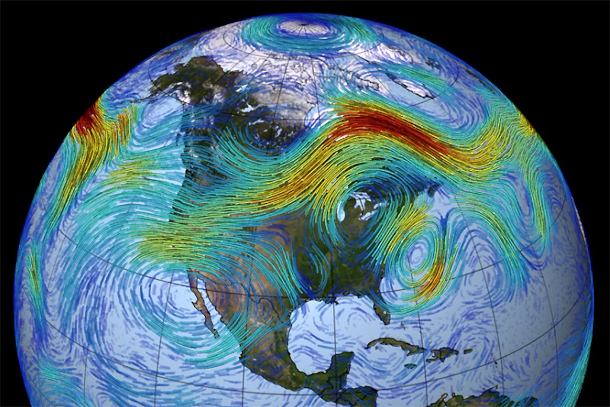

MANN: Yeah, well there are a number of things going on here. At the most basic level, you warm up the planet, you warm up the oceans, they evaporate more moisture, more water vapor, into the atmosphere, and the warmer atmosphere pulls more moisture. So when you do get rainfall, when you do get precipitation, you get more of it. And so we tend to see a far greater incidence of these very heavy rainfall events and flooding events. That's ingredient number one, and that's very basic. It's based on the laws of thermodynamics. It's rock solid. There's something else going on which is a little more complicated, and it has to do with the way that the pattern of how the planet is warming up with the Arctic warming faster than, say, the middle latitudes. That changes the overall temperature structure in the atmosphere, which influences the jet stream. And so we tend to get these configurations like we have right now, where the jet stream gets locked into one of these very wiggly patterns. If you look on a weather map right now, you'll see the jet stream is sort of undulating wildly. And with each of those ridges and dips in the jet stream are surface low and high pressure systems, extreme weather systems. And so right now we're seeing this array of low and high pressure systems with extreme weather, very hot weather in certain areas, very rainy, wet weather in other areas that's adding to the extreme nature of these events that we're seeing right now. And there's mounting evidence that the way the planet is warming up is making these sorts of events more frequent.

Warming of the Arctic affects the jet stream, increasing its undulation and therefore its extremes. Our guest Michael Mann compares it to Van Gogh’s “Starry Night” painting. (Photo: NASA)

CURWOOD: So the formula is, warmer planet speeds up the hydrologic cycle, except it's also creating chaos it sounds like in the weather systems.

MANN: Yeah, if you like. In fact, it's a good choice of words, because somebody asked me, somebody pointed to me on social media today, pointed out that this very odd jet stream pattern right now, it's a very unusual jet stream pattern with these huge wiggles up and down. And they said, you know, have you ever seen anything like it before, and I replied with an image of a starry night, Van Gogh's Starry Night, because it almost looks like that. The chaos that is present in Van Gogh's Starry Night is the sort of chaos that is present in our atmosphere right now and again, climate change appears to be making that sort of behavior more common.

CURWOOD: Now, what kind of differences and similarities in disaster response and preparedness are we seeing in Central Europe vis a vis West Africa? I mean, how has that affected the scale of the disasters in each place?

West Africa and Central Europe both recently experienced extreme flooding. However, a stark difference in resources has made the scale of the disaster much worse in the Global South. Flooding in Maiduguri, Nigeria, is pictured above. (Photo: Mr. Snatch, Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0)

MANN: Yeah, well, I mean, there are a number of problems here, one of which is that we're seeing these simultaneous disasters, and so there's a certain amount of resources that we can bring to bear when it comes to emergency and disaster relief, and there's only so much that we can do. There's only so many resources that we can bring to bear. And we're here in the United States, for example. We're becoming increasingly thinly spread because we've got wildfires in the West. We've got flooding in the East. We get these simultaneous weather disasters where we simply don't have the capability to deal with all of them at the same time, adding to the problem, you look at a place like West Africa, and it doesn't have the wealth that we have here in the United States or that they have in Europe, and so there's a real disparity there. They don't have the infrastructure, they don't have the wealth, and so they're hit that much harder by the impacts of these devastating extreme weather events. And it sort of communicates a larger problem, an ethical problem, here, which is that those countries, those people who had the least role in creating this problem in the first place, are, in many cases, truly bearing the brunt of the problem. We see that in the developing world, the Global South, where they're seeing some of the worst consequences of climate change that was caused by wealthy industrial countries in the north, like the United States and Europe. And so there's a very strong argument then that we need to see far more resources provided by the wealthy nations to these other countries to help them deal with the disasters they're already forced to deal with.

CURWOOD: What kinds of steps should nations and communities be taking, then to help these communities that have fewer resources?

MANN: Yeah, great question. Well, at the I believe it was cop 27 so two years ago, the Conference of the Parties the United Nations Climate Summit, there was a very important breakthrough on what was known as loss and damage. Basically, it was an agreement by the nations of the world that the wealthy, industrial country. Countries will provide assistance, financial assistance, to developing countries. Now, what wasn't agreed upon was the amount of assistance, and thus far, we haven't seen anywhere near the amount of assistance that is necessary for them to cope with, again, the devastating impacts they're already coping with.

CURWOOD: So what should we be doing, both here in the US and abroad, to better prepare communities for the climate extremes of the future?

The multi-year global temperature trend line has not yet passed the mark of 1.5-degree Celsius above preindustrial levels. However, we will cross that line soon if drastic emissions reductions don’t happen rapidly, Michael Mann warns. (Photo: Chris Yarzab, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

MANN: Yeah, so in addition to helping our neighbors, which means providing more financial assistance, the United States could certainly provide more financial assistance to this fund, this loss and damage fund to help the rest of the world. There are a lot of things that we need to do here within our own country, because we have disparities of our own. We see that here in Philadelphia, there's a huge climate justice problem in that those who are dealing with the worst of urban heat island effects, typically those are low income neighborhoods, and so they experience the worst of that extreme summer heat. They experience the worst of the flooding because they're in the low-lying regions that are undesirable, precisely because they're so prone to flooding. And so there is a disparity there, and that requires us to provide assistance. Cities, municipalities, states and the federal government needs to provide resources to help, especially those frontline communities, deal with the consequences that they're already experiencing. It's the same story here, even within our own country, financial disparity leads to differential impacts, impacts that are felt much more strongly on the part of those with the least wealth.

CURWOOD: So, there are some projections that show that the global average surface temperature of the planet now exceeds more than one and a half degrees centigrade from the pre-industrial level. This was the target that the UN and the Paris Climate Accord was pushing us towards. In your view, have we passed that threshold? And if so, what does it mean?

MANN: Yeah. So there's some good news and some bad news here. The good news is that we haven't passed that threshold. It's defined really by the trend line. And so what happens global temperatures sort of wiggle from year to year, up and down, to some extent, because of natural events like El Nino events. This past year and a half, global temperatures have been elevated by a major El Niño event, and that's a natural event and that warmth is now subsiding as we head into the opposite state of the climate system, the so called La Niña, where the Tropical Pacific cools down, and that impacts weather patterns around the planet in the opposite way. And so we see those wiggles up and down. And what happens now, when you get an up wiggle, the temporary spike because of an El Niño, it adds to the trend line, and you temporarily breach those limits that we talk about, like 1.5 Celsius or 2 Celsius, and so we've temporarily breached those thresholds. But it's temporary. The problem is when the trend line itself, not the fluctuations around the trend line from year to year, but the trend line itself, when that crosses 1.5 Celsius, three degrees Fahrenheit, basically, that's when we are subject to some of the more devastating consequences of that level of planetary warming. So that's the good news. We haven't crossed 1.5 Celsius three Fahrenheit yet, by the definition that's actually used by the scientific community, here's the bad news, we will cross that threshold in a matter of years now if we fail to bring our carbon emissions down dramatically. And so we will very soon rise above this level of truly dangerous planetary warming if we don't take immediate action. And so there's both, as I like to say, there's urgency here, but there's agency. It's not too late for us to take the actions necessary to avert catastrophic levels of warming.

Michael Mann is a distinguished professor at the University of Pennsylvania and one of the world’s leading climate scientists. (Photo: Joshua Yospyn)

CURWOOD: Sure feels like catastrophe in West Africa and parts of Central Europe and along the Carolina coast, wherever the fires are right now, Professor.

MANN: That's a fair point. And you know, we're not going to avert dangerous climate change, because by many measures, it's already here. What we can avert are some of the potential tipping points where we, for example, see the collapse of the major ice sheets or other similar devastating threshold events. We can still avoid those truly planetary scale catastrophic consequences if we take action, and we take action quickly.

CURWOOD: Thank you for the hope. Professor Michael Mann is a distinguished professor, I believe, at the University of Pennsylvania, and one of the world's leading climatologists. Thank you. So much for taking the time with us today.

MANN: Thank you, Steve, always a pleasure.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth