Three Mile Island to Power AI

Air Date: Week of September 27, 2024

The deal between Microsoft and energy supplier Constellation would reopen Unit 1 of the Three Mile Island nuclear plant. (Photo: Dave Monteverdi, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

To meet the energy needs of artificial intelligence Microsoft has inked a major power purchase deal with the owners of Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania. A nuclear power reactor there underwent a partial meltdown in 1979. Its unaffected twin reactor operated until 2019 and would provide a carbon-free source of power. Evan Halper reports on the energy transition at the Washington Post and joins Host Jenni Doering to explain the hurdles of getting the shuttered nuclear power plant back online.

Transcript

DOERING: Propelled by the AI boom, tech giants are hunting for new ways to feed AI’s insatiable appetite for energy. And Microsoft is betting big that zero-emissions nuclear power could be the answer. The company has inked a major deal with the owners of the plant that had the most serious nuclear power incident in US history. In 1979 the Three Mile Island nuclear plant along the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania experienced a partial meltdown of one of its two reactors. A malfunction of the cooling pumps combined with operator error led to the overheating of the reactor core and a small release of radioactive material. No one died in the immediate aftermath and the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission estimates that the roughly 2 million people in the area received on average just a fraction of a chest x-rays worth of radiation. But the failure of Unit 2 at Three Mile Island became a symbolic touchstone for the anti-nuclear movement. The other reactor at Three Mile Island kept operating up until a few years ago, when the regional grid became flooded with cheaper energy from gas-fired power plants. Three Mile Island is still hooked up to the grid but with the addition of all that gas power, upgrades to the grid may be needed to bring the nuclear plant back online as soon as 2028. Evan Halper is a business reporter at the Washington Post who covers the energy transition, and he joins me now. Evan, welcome to Living on Earth!

HALPER: Thanks for having me. Great to be here.

DOERING: So, Evan, I wasn't around back then, but I do know that in 1979 the Three Mile Island accident fueled an intense wave of anti-nuclear protests across the country. What has been the public reaction to the possibility of reopening this plant now?

HALPER: It's very mixed. This is not the 1970s. We're not seeing a, you know, an outpouring of protest. We are seeing some protest, but we're also hearing from a lot of politicians in the community who are saying, you know, this plan is an economic anchor. These are really good paying jobs, and then there's all kinds of ancillary jobs that get created. This could generate billions of dollars of economic activity in the region. And so, you're seeing a lot of support from the governor's office in Pennsylvania down to local officials there. But you also have nuclear safety advocates who say that politicians are pushing the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to fast-track plants, and there are still big risks here. I mean, you will talk to some people who say they have health problems which they attribute to the partial meltdown in the 1970s. Again, the government says that they didn't find any major adverse health effects related to that, but these things are hard to prove. So, there's this weighing of okay, we have this climate crisis at the same time we have these nuclear safety issues, and because there's so much concern that we're not taking enough action to deal with the climate crisis, there's a renewed interest in nuclear.

As energy intensive AI technology ramps up, Microsoft is seeking more emissions-free sources of power. (Photo: Mike Mozart, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: And just to be clear, which reactor at Three Mile Island would actually be started back up?

HALPER: So that's an important point. This is not the reactor that partially melted down. That unit shut down after the accident, and it was never reopened. This was a unit that operated right next to that unit and never had a meltdown accident, did not have those problems. It shut down in 2019 mostly because nuclear energy couldn't compete with other cheaper forms of energy, particularly natural gas. I mean, you know, there was the shale boom in Pennsylvania, and natural gas got super cheap, and it just was no longer economic to be selling nuclear power, and so they shut the plant down.

DOERING: And to what extent would this nuclear power make a significant dent in Microsoft's carbon footprint?

HALPER: Well, Microsoft will argue it will make a huge dent, talking about the amount of power that goes to about 800,000 homes. And nuclear power suddenly has great interest in the tech industry because it creates power emissions free. And because there's so much trouble getting enough wind and solar online to meet these surging energy demands that this country is seeing, in large part because of AI, the tech companies are scrambling to find as much zero emissions energy as they can. So, what Microsoft will do here is they'll, they'll use their accounting to say, well, we're purchasing all this clean energy, we're bringing it onto the regional power grid, and because this clean energy would not have been there, but for Microsoft buying this power contract, we get to claim this energy as ours. Whether the electrons actually go to power its data centers is another issue. They actually probably will not. It'll just go onto the grid, but Microsoft is the one bringing that power onto the grid. So, they take credit for zero emissions, even oddly, if they're using energy that's fossil generated from gas or even coal, when they power their data centers. Because they bought all this energy from Three Mile Island, they can claim we're net zero at our data center.

The Inflation Reduction Act, President Biden’s signature climate law, invested heavily in nuclear power. (Photo: Prachatai, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: So, Microsoft is bankrolling the reopening of Three Mile Island by this energy company that runs it, Constellation, and they will have exclusive rights to buy that power. What are some of the concerns with that approach?

HALPER: Well, like all power, but nuclear in particular, a lot of subsidies go into it. One of the reasons that this deal can happen, Constellation is very upfront about this, is because of the Inflation Reduction Act, which was President Biden's signature climate law. That includes really lucrative subsidies for nuclear power. It's a production tax credit. And then it raises the question, were there subsidies intended for the community benefit, or were they intended for one tech company to be able to use them? So that will be a robust debate that we'll be hearing about as the process of trying to reopen this plant moves forward.

DOERING: So how might this setup of a single company buying all this power affect the average energy consumer?

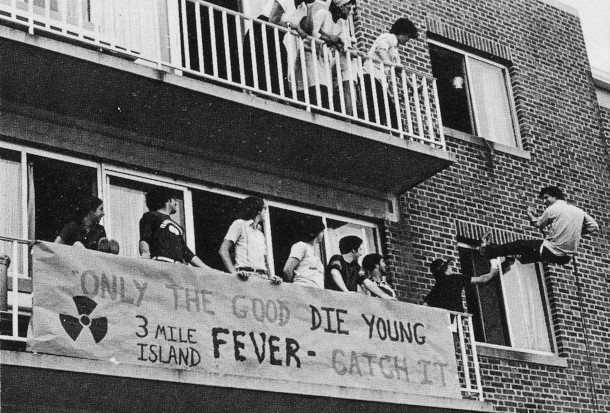

The Three Mile Island partial meltdown in 1979 fueled a wave of anti-nuclear protest across the country. Our guest Evan Halper says we aren’t seeing that same level of pushback this time around. (Photo: Franklin and Marshall College, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

HALPER: That's one of those questions that we're trying to figure out. And a lot of folks are debating. In this case, Constellation, the owner of the Three Mile Island plant, says, look, we have all the infrastructure in place already, we don't have to order all kinds of new parts and figure out supply chains, it's already there. This will cost about a billion and a half dollars, and we're going to pay for that. We're not asking other rate payers to pay for it. And I talked to Microsoft yesterday, they won't say what exactly they're paying for this power, but it's a higher rate than power off the grid, and they're saying that basically built into the rate is all the costs of the infrastructure to cover all this. But anybody who's looked at the nuclear industry over the years will tell you they never meet their targets for costs, and this has never been done before. They've never taken a nuclear plant that's been headed into decommissioning, been shut down and tried to restart it. And so, we don't know what this process will be like. We don't know how expensive it'll be, and if the cost overruns start to go into the billions of dollars, it becomes a question of, well, who's paying for this? So, there are issues of fairness and a lot of questions about, how will this affect rate payers? How will this affect taxpayers? Is this a fair deal for everyone?

DOERING: So, what are the barriers to getting a closed nuclear power plant going again?

HALPER: Well since it's never been done before, and nothing at the Nuclear Regulatory Commission is simple, you know, what will be involved is a series of federal, state and maybe even local inspections and reviews, so much so that it'll take a few years to make this happen. And then the other part of this is hooking it into the power grid. I mean, one of the big attributes of this project is that they're saying, we're going to hook this into the regional grid, which is, it's called the PJM Interconnect. It's 13 states, and Washington, DC. And right now, getting projects into the PJM interconnect is challenging because, like the rest of the country, the PJM grid has been suffering lack of investment in infrastructure, and it's taking longer and longer to hook in new big power projects. And the question is, will they be able to move as fast as Microsoft and Constellation want them to move to get this project hooked up to the grid and producing power.

DOERING: Right, I mean, it sounds like even if they have all this energy ready to go, this nuclear power plant gets running again, if the grid can't handle it, you know, not much use.

Evan Halper is a business reporter for The Washington Post who covers the energy transition. (Photo: Courtesy of Evan Halper)

HALPER: Yeah, this is a problem that's emerging all over the country. The grid has not had the kind of investment it needs, and that's for a number of reasons. It's not just financial. It's also permitting issues. There's just fights over big transmission projects going across state lines, and for example, in this case, Pennsylvania is going to produce all this energy from Three Mile Island. It's going to be used mostly or purchased by a buyer who has data centers down in Virginia, but that infrastructure needs to carry that power all over the grid, and it becomes a question. Someone in Maryland may say, wait, our rate payers are going to be affected by this, because we may need to build more infrastructure to bring that power down to these data centers in Virginia. Virginia's getting the tax revenue from the data centers. Maryland's getting nothing. What's going on here? We don't like this deal, and these things become really tricky, really fast.

DOERING: Evan, what do you think this move by Microsoft means for the future of powering AI?

HALPER: I think it's a really big deal, and it raises all kinds of questions about the lengths these tech companies will go to to acquire the energy that they say they need. So, when I was at Microsoft yesterday, I was talking to their Energy Lead about, when is this going to stop? When is the growth going to stop? I mean, you just bought an entire nuclear plant's worth of energy, and AI is in its infancy. You're at the front end of this revolution, and you're going to need so much energy to develop this. And the trends we've seen over just like the last couple of years, are not sustainable for much longer. Like, how long is this going to continue? And that's a question they don't like to get, and they don't really give a clear answer to, they express confidence that, well, within five years, things should level off. They talk about how AI itself can make AI more efficient. And you know that all sounds great, and it's true. I mean, AI is much more efficient, or these data centers are run much more efficiently than they were 10 or 20 years ago, but their energy needs are still eclipsing the innovation that is making them more efficient. They're not becoming nearly efficient enough to curb the huge trend lines in energy demand growth.

DOERING: Evan Halper is a business reporter for The Washington Post who covers the energy transition. Thank you so much, Evan.

HALPER: Thank you. It was great to be here.

DOERING: Microsoft provided a statement about its deal with Constellation Energy that reads in part: “The agreement will bring a significant supply of net-new, reliable, carbon-free electricity to the PJM power grid, the regional transmission organization covering 13 states, and complements Microsoft’s 34 GW carbon free energy portfolio of renewable projects across 24 countries.” To read the full statement from Microsoft as well as one from Constellation Energy head to the Living on Earth website, loe dot org.

We have reached out to Constellation Energy for a statement and are awaiting their response.

Microsoft Statement:

“Microsoft and Constellation Energy announced a power purchase agreement (PPA) to restart an 835 MW nuclear facility in Pennsylvania, renamed as the Crane Clean Energy Center (CCEC.) Under the agreement, Microsoft will purchase energy from the renewed plant to help decarbonize the grid in support of our commitment to be carbon negative.

The agreement will bring a significant supply of net-new, reliable, carbon-free electricity to the PJM power grid, the regional transmission organization covering 13 states, and complements Microsoft’s 34 GW carbon free energy portfolio of renewable projects across 24 countries.

For more information about this agreement, and Microsoft’s approach to carbon-free energy, please see the Microsoft Cloud blog.”

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth